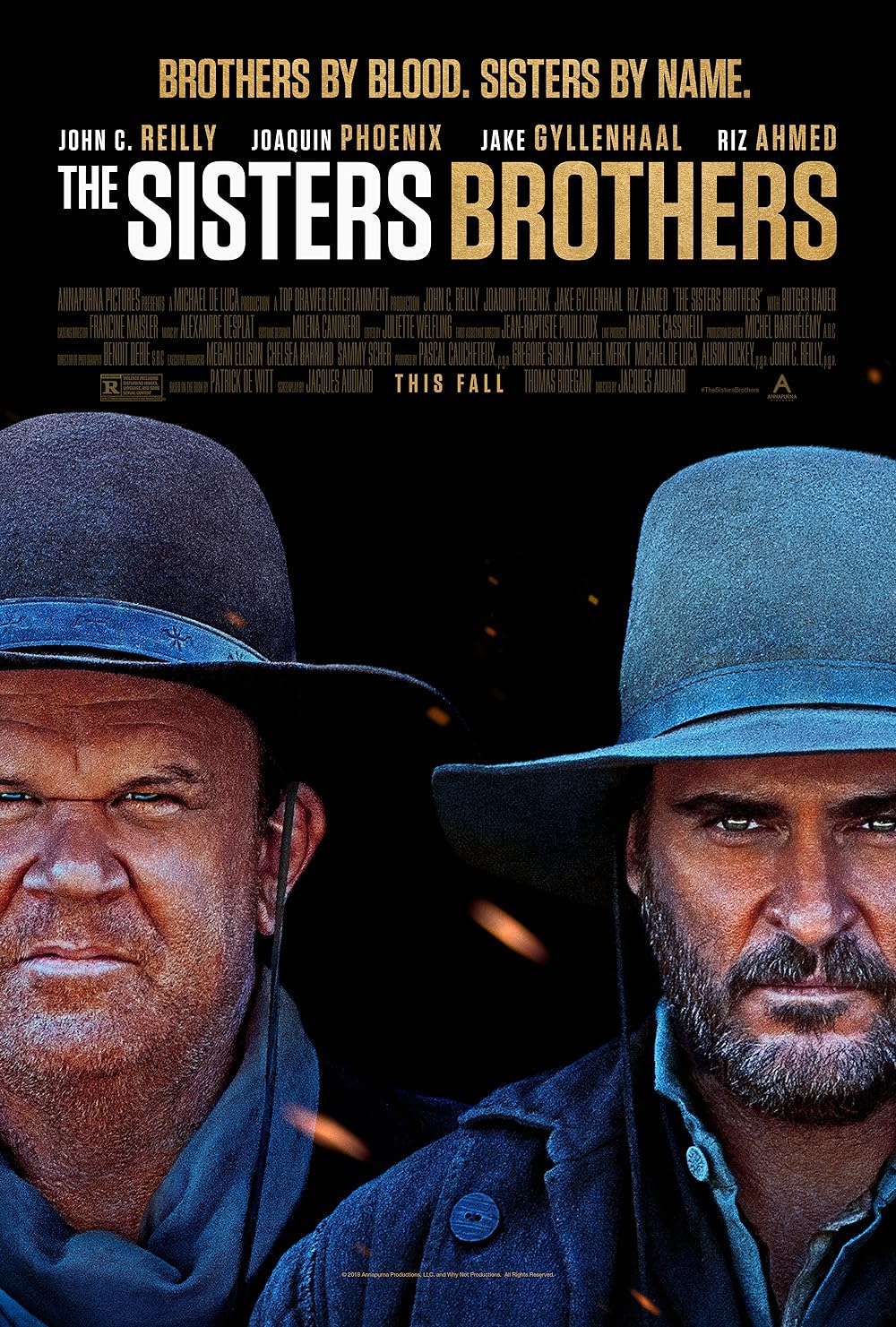

The Sisters Brothers

By Brian Eggert |

The Sisters Brothers, a violent and episodic Western that grows more affecting as goes on, opens as Eli and Charlie Sisters, two hired guns of the savage frontier, approach a farmhouse where their target has holed-up with an armed gang. The night’s thick bronze blackness saturates the scene. The siblings attack and, in the volley of gunfire, only the brief, fiery discharges from their pistols flash in the dark. Shot from a distance, the sequence is dazzling and scary, but not so much as the next shot, as the siblings—assassins, paid thugs, and criminalized jacks-of-all-trades—approach the farmhouse and dispose of its many occupants with ruthless efficiency. Eli Sisters, the older and more competent of the two, is played by John C. Reilly in a performance that uses his mutual capacities for comedy and tragedy. Likewise, Joaquin Phoenix, who’s carried a persona of displacement and unrest in several roles, plays Charlie Sisters, a drunk whose killer instincts feed his reckless ambition to become a criminal overlord. Their unceremonious elimination of the opposition in this first sequence should not suggest a comically violent Western that uses death as a punchline, a characteristic of cooly self-aware post-modernism; rather, it gives way to a poignant and telling moment just afterward, where the brothers see a horse, its flesh on fire, galloping away from a burning barn. Eli desperately enters the blaze to save what few horses he can, while Charlie watches, exasperated by his brother’s sympathy for the doomed animals.

A rich tapestry of Western themes that have been lovingly weaved into a picaresque, The Sisters Brothers is the first English-language film from French director Jacques Audiard, the auteur responsible for A Prophet (2009) and Rust and Bone (2012). The screenplay by Audiard and Thomas Bidegain was based on the 2011 novel by Patrick Dewitt, winner of several literary awards, and follows the basic plot of the novel. However, Audiard’s usual blend of harsh realism and lyrical imagery emerges here, resulting in a revisionist Western of the highest order. Like many non-Western filmmakers who explore this genre (including Ang Lee, Andrew Dominik, Kim Jee-woon, Martin Koolhoven, Kristian Levring, and John Hillcoat), Audiard rethinks its usual narrative trajectories in compelling ways. The story goes in a different direction than it initially seems to, and Audiard avoids reducing his characters to basic tropes. But the material fits nicely into Audiard’s body of work, in that The Sisters Brothers has both his verist sensibility and an element of Western mythology running through its bones.

Set in 1851, the film opens in Oregon City, where the more sensible and thoughtful brother Eli tries to convince his wildcard brother Charlie to consider giving up the outlaw life. He pleads for their latest assignment to be their last, a notion to which Charlie refuses to commit. Charlie isn’t much of a talker; he’s a man of action and seems to command his elder brother. Their boss, known only as the Commodore (Rutger Hauer, appearing in a wordless role), has tasked the Sisters with extracting information from Hermann Kermit Warm (Riz Ahmed), a supposed thief who has disappeared. Their job isn’t to find the quarry, however; that burden falls on a private detective, the learned Morris (Jake Gyllenhaal), who spies the countryside for Warm. For the first half of the film, Audiard alternates scenes between the Sisters, who follow several days behind, and those between Warm and Morris, who meet in Jacksonville, Oregon, and form an unlikely friendship. The outing takes us from Jacksonville to a fictional boom town called Mayfield, named after its female overlord (Rebecca Root). After a brief visit to Babylon by the Bay for a touch of so-called civilization, the two groups encounter each other at a prospecting site.

Set in 1851, the film opens in Oregon City, where the more sensible and thoughtful brother Eli tries to convince his wildcard brother Charlie to consider giving up the outlaw life. He pleads for their latest assignment to be their last, a notion to which Charlie refuses to commit. Charlie isn’t much of a talker; he’s a man of action and seems to command his elder brother. Their boss, known only as the Commodore (Rutger Hauer, appearing in a wordless role), has tasked the Sisters with extracting information from Hermann Kermit Warm (Riz Ahmed), a supposed thief who has disappeared. Their job isn’t to find the quarry, however; that burden falls on a private detective, the learned Morris (Jake Gyllenhaal), who spies the countryside for Warm. For the first half of the film, Audiard alternates scenes between the Sisters, who follow several days behind, and those between Warm and Morris, who meet in Jacksonville, Oregon, and form an unlikely friendship. The outing takes us from Jacksonville to a fictional boom town called Mayfield, named after its female overlord (Rebecca Root). After a brief visit to Babylon by the Bay for a touch of so-called civilization, the two groups encounter each other at a prospecting site.

With much of the film taking place during this journey, Audiard’s performers dominate the scenery. Reilly’s complex and funny performance recalls his appearances in Magnolia (1999) and We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011), where the actor blends his comedic chops with a dramatic stroke for a strange, effective balance only he could achieve. Eli wants so badly to settle down, as evidenced by his interest in the modern, tamed world—he buys a newfangled invention called a toothbrush at a general store and savors the comforts of a San Francisco hotel. A long time ago, a woman gave him a shawl with a spritz of her perfume, and he carries it with him, smelling its fragrance to both cure and aggravate his homesickness. When he visits a prostitute (Allison Tolman) in Mayfield, he pleads with her to act out a scenario where she gives him the shawl, and the scene is heartbreaking, if sadly comic. Charlie is less interested in modern conveniences or settling down. He enjoys killing and drinking, though he’s better at the former. His alcoholism, fuelled by the same self-destructive turmoil that inspired him to kill their abusive father, leads to setbacks. Drunk, Charlie shoots up saloons and, the next morning, irredeemably hungover, he falls off his horse on the trail. Each man is personally broken and dependent on the other, making their relationship tender and volatile.

By contrast, the dynamic between Warm and Morris is more hopeful. Both are decent, educated men who have found each other in unkind and brutal company among other frontiersmen. Warm, an idealist, hopes to found a new society in Dallas, which Audiard and Bidegain based on the French political movement called Saint-Simonianism—a concept rooted in socialist equality that abandons capitalist motivations in favor of the advancement of the human race through science and egalitarianism. Compelled by such ideas, Morris betrays his mission for the Commodore, and alongside Warm, he sets out to develop the film’s MacGuffin: A chemist, Warm has written a formula for a liquid that when dispersed causes the gold in the riverbed to glow, eliminating the need for the heavy labor, tools, and machinery involved in prospecting. But once they extract enough gold using this method, they plan to head toward Dallas and start their new community. At the same time, the Sisters are supposed to find Warm, torture him for the specifics of his formula, and then return it to the Commodore.

The Western symbolism in The Sisters Brothers seems evident at first, with Warm and Morris representing the advancement of civilization, while the Sisters remain symbolic of the barbarous Wild West that must be tamed. But the narrative grows beyond the fateful encounter between the brothers and their initial objective, and that’s when the film builds from an enthralling Western yarn into something more ruminative and melancholy. Eli convinces Charlie to abandon their hard-earned reputation as cold-blooded gunslingers, and instead, they join Warm and Morris in their venture. Eli will settle down, open a store; Charlie will kill and take over the Commodore’s role as Oregon’s kingpin. Of course, nothing works out as they hope it will. Just as the film begins to resemble a tall tale, Charlie’s impulsive greed, combined with the acidic goop mixed by Warm, results in disaster. Then again, perhaps the American metaphor, while not traditional, is more appropriate than it initially appears. Scarred by avarice and chased by their demons, the brothers must return home to an impossibly comforting domestic dream that, strangely, recalls the final scenes of Audiard’s Dheepan (2015).

The Western symbolism in The Sisters Brothers seems evident at first, with Warm and Morris representing the advancement of civilization, while the Sisters remain symbolic of the barbarous Wild West that must be tamed. But the narrative grows beyond the fateful encounter between the brothers and their initial objective, and that’s when the film builds from an enthralling Western yarn into something more ruminative and melancholy. Eli convinces Charlie to abandon their hard-earned reputation as cold-blooded gunslingers, and instead, they join Warm and Morris in their venture. Eli will settle down, open a store; Charlie will kill and take over the Commodore’s role as Oregon’s kingpin. Of course, nothing works out as they hope it will. Just as the film begins to resemble a tall tale, Charlie’s impulsive greed, combined with the acidic goop mixed by Warm, results in disaster. Then again, perhaps the American metaphor, while not traditional, is more appropriate than it initially appears. Scarred by avarice and chased by their demons, the brothers must return home to an impossibly comforting domestic dream that, strangely, recalls the final scenes of Audiard’s Dheepan (2015).

Shot in Romania and Spain, The Sisters Brothers uses the landscape, captured in gorgeous location filming by cinematographer Benoît Debie, in a manner similar to that of Anthony Mann (The Naked Spur, Man of the West). Mann used natural vistas not to celebrate the otherworldly spectacle and wildness of the American West that would be civilized by Manifest Destiny, but as a sublime reflection of his characters—complicated people with streaks of both goodness and unforgiving cruelty. Here, the countryside is a land of opportunity fraught with countless dangers and meant only for skilled killers and the brave. Eli and Charlie survive numerous shootouts thanks to their efficiency with a gun. Audiard shoots the action in brief, tense spurts of violence that never fail to bring the film’s dark humor to a sudden halt, therein reminding the viewer what kind of people this story is about. And Alexandre Desplat’s excellent, thumping, at times playful score maintains a relentless momentum to the film’s rambling odyssey.

Audiard’s appreciation of the underrepresented genre is manifest, as The Sisters Brothers has a physical quality in its making, which he enhances with his own more poetic touches. Take an unforgettable scene where a horrific spider crawls into Eli’s mouth and down his throat; once there, it lays eggs, and the resultant sickness gives way to hallucinations of Eli’s romantic desire. This sort of moment contains the at once savage and fantastical qualities the West. Audiard also beautifully frames the strengths of his actors, with Reilly a vulnerable and beleaguered brother to an unstable force; however, Phoenix lends Charlie incredible dimension in the final act, when their relationship transforms in unexpected ways. With memorable performances throughout this extraordinary cast, The Sisters Brothers is another Audiard film whose tonality withstands categorization. It’s neither a straightforward Western nor merely revisionist, and it’s often funny yet has an undercurrent of tragedy. However incongruous such a thing may seem, Audiard’s vision is complete, moving, and original.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review