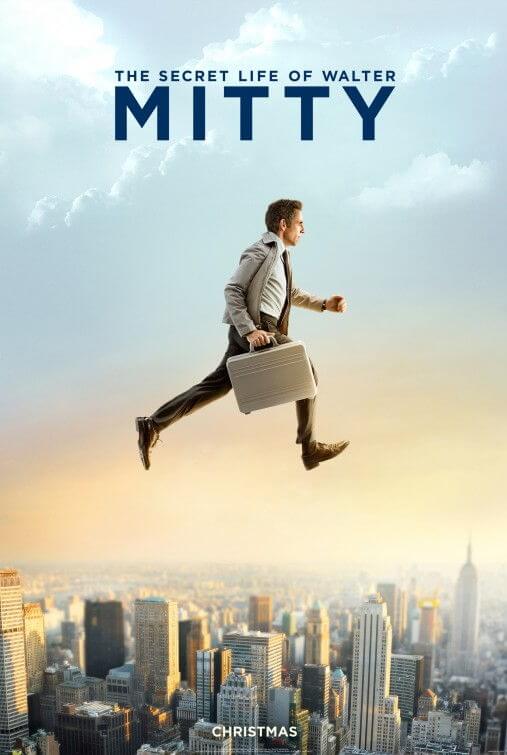

The Secret Life of Walter Mitty

By Brian Eggert |

Ben Stiller directs and stars in The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, an adaptation of James Thurber’s original two-and-a-half-page short story first published in The New Yorker in 1939. Thurber’s story was about a daydreamer who, on the way to the grocery store and his nagging wife’s hair salon, imagines himself completing extraordinary feats of heroism and defiance. Amid his detached reveries, he out-flies a violent storm, performs breakthrough surgery, and carries out a suicide mission as a Royal Air Force pilot. All of them reflect and serve to counteract the stagnations of his everyday life. By the end, he imagines himself stoically facing a firing squad, while his real-life self is forever trapped in the doldrums of reality. Such a poignant—but undeniably downer—message about modern life is unlikely in a Hollywood picture, as demonstrated when Thurber’s story was put into Technicolor in the 1947 production of The Secret Life of Walter Mitty starring Danny Kaye, where, in a fabricated happy ending, Kaye’s harangued book editor finally stands up for himself and stops evading bullies by escaping into his imagination.

Stiller and screenwriter Steve Conrad have envisioned a similarly upbeat narrative for this long-in-development update. After almost two decades of false starts at various studios and a mixed bag of comedy superstars attached (Jim Carrey, Mike Myers, Sacha Baron Cohen, etc.), Samuel Goldwyn, Jr., whose father produced the 1947 version at MGM, finally sees his toiling result in a finished film. Here, Walter (Stiller) works as a photo negative archivist for Life magazine, which has just been acquired by a larger company determined to downsize and move the magazine online, a transition overseen by Walter’s new boss, a smarmy, bearded Adam Scott. Walter’s occupation may seem strange given that Life stopped publishing a magazine back in 2000, but it contains a biting symbolism for the protagonist, a sheltered office worker who hasn’t “lived” at all. In an early conversation with an eHarmony customer service rep voiced by Patton Oswalt, Walter is asked, “Have you done anything noteworthy or mentionable?” At this, Walter stares off, zoning-out into one of his catatonic daydreaming sessions.

The film’s first half concerns Walter’s workday, his smug new boss’ executive entourage poking fun at his virtually unconscious daydreaming like high school bullies. Meanwhile, Walter works up the nerve to approach his office crush, Cheryl (Kristen Wiig). Each awkward encounter is interrupted by one of his cutaway fantasies, realized to outlandish effect by the big-budget CGI of this $90 million production. One sequence has Walter and his boss fighting over a Stretch Armstrong doll (never mind why), battling it out on the streets of New York City in a scene that feels ripped from The Avengers or a Spider-Man movie. Another sequence visualizes a tragic romance between Walter and Cheryl, where our hero grows older and smaller in a spoof that confuses the relationship between time and age from The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, a film Walter admits he never watched. These jokey fantasies feel more akin to Stiller’s Hollywood satire Tropic Thunder and come filled with in-joke humor and overblown visual gags.

Before long, Stiller and Conrad’s story veers into semi-serious adventure territory, far removed from the silliness that occupies the first half. Walter receives the last photo reel of daredevil photo-journalist Sean O’Connell (Sean Penn), whose “quintessential” cover photo for Life’s last issue has gone missing. Without much need of a push, Walter uncharacteristically catches a flight to Greenland on a globe-trotting mystery to find O’Connell: his stops in Iceland and Afghanistan have Walter jumping out of a helicopter, swimming with a shark, evading volcanic eruptions, and climbing the Himalayas. At any moment, we expect the film to cut back to Walter daydreaming in his cubicle again, but instead, we’re meant to swallow his sudden bravery and extrovertedness. All the while, the impetus for Walter’s sudden break in character remains curiously unexplained. With each new exploit, Walter needs to dream less and less, and as this happens, the film moves further and further away from Thurber’s story, while also moving closer into standard commercial fare.

Speaking of commercialism, Stiller jams product placements down our throats by showcasing the Papa John’s pizza chain as Walter’s first job as a teen, the ironic trade Walter took after his father died, which in turn caused the character’s lifelong fearfulness. Our eyes roll at the extreme product placement when he finds a Papa John’s in Iceland. Much like the film as a whole, this detail takes a potentially moving concept and mutates it into something hollow and meaningless. Even the look of the film’s second half resembles a Mountain Dew or Nike ad, Stiller scaling mountainsides and riding a skateboard down a hillside at top speeds like a true Gen X-er. For earlier scenes, cinematographer Stuart Dryburgh dwarfs Walter in the frame and surrounds him in modern architecture and office spaces reminiscent of M. Hulot in Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967), immersed in the staid, grayish color palette of modernity. This is when The Secret Life of Walter Mitty looks its best; later on, the film resembles an extended Monday Night Football commercial.

One needs not look beyond Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985) for a spiritually faithful take on Thurber’s story, even if that film’s plot has no direct linkage to The Secret Life of Walter Mitty. Although Gilliam and co-writer Charles McKeown credited other sources as inspiration, such as Fellini’s 8 ½ and Orwell’s 1984, the structure of Thurber’s text is certainly present in Brazil, complete with a fatalistic finale where the cruel world stomps out the pesky daydreamer. Stiller’s film means well and general audiences will likely enjoy what they see, but its tonal inconsistency and overt commercialism frustrate the more discerning viewer to no end. Thurber’s story becomes a launching pad for something more, but in this case, more plot means less substance. Less about Walter Mitty’s secret life than his actual, perfectly romantic, impossibly realized adventures, the film loses itself in a fantasy world all its own and never fully embraces the everyday balance of reality and imagination.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review