Reader's Choice

The Salesman

By Brian Eggert |

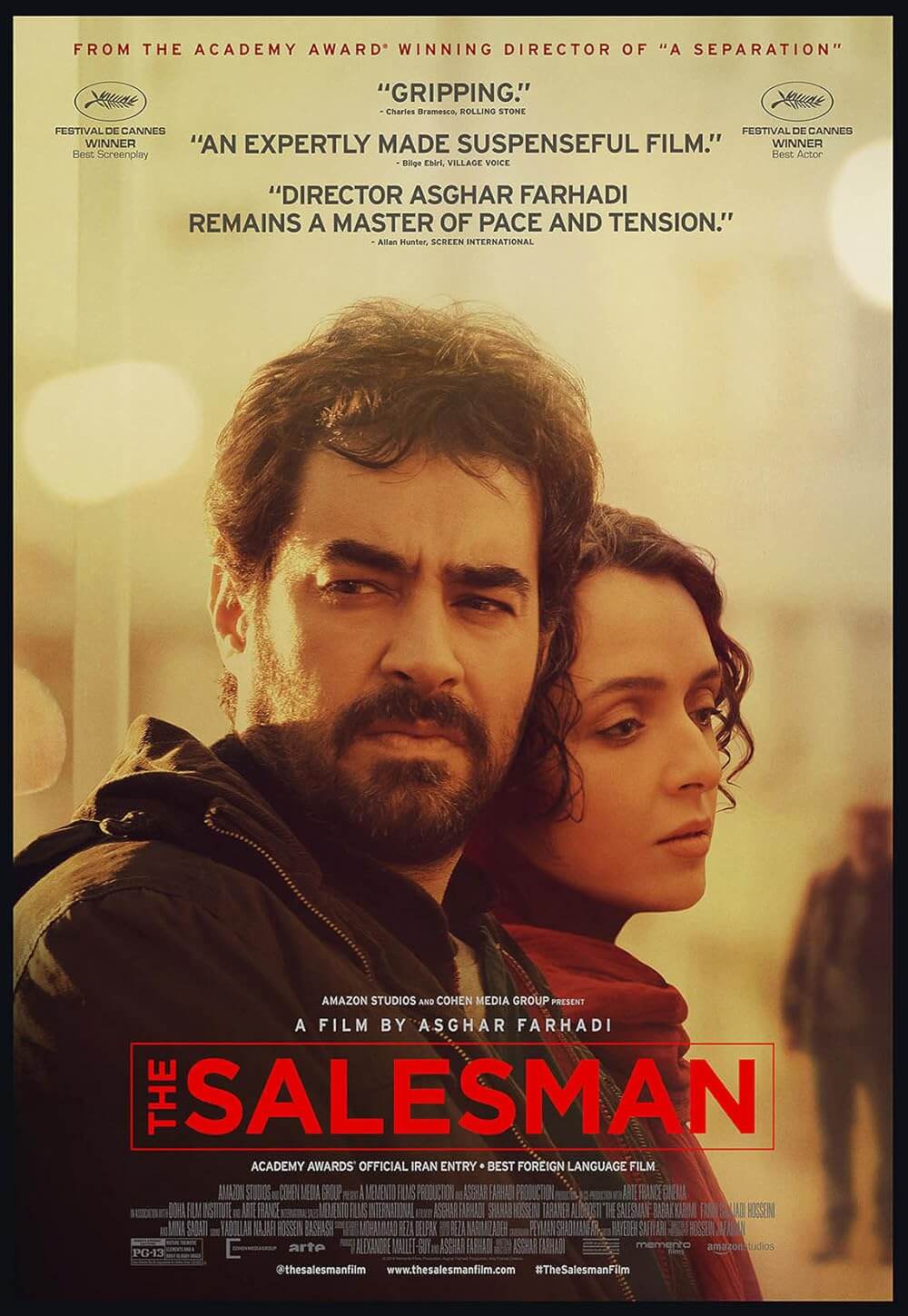

In Asghar Farhadi’s The Salesman, the Iranian filmmaker crafts a moral dilemma to which there is no solution. Those familiar with his cinema will recognize his tactic and usual narrative framework. He begins with a minor indiscretion, a passable micro-offense that barely registers. Gradually, the misdeed unravels into a life-altering event, raising questions about the consequences of our actions, no matter how trivial. Farhadi also challenges the viewer’s sympathies. Although he invests us in central characters at the outset, before long, we begin to scrutinize their behavior and reconsider our initial impressions. By the end, no one is innocent, and we’re left questioning how we feel about these characters and what they have done. Farhadi’s dramaturgy functions like a stage play, while his naturalist aesthetic places the story in the real world. This dynamic might seem incongruous but represents the filmmaker’s distinct, neorealist style. Yet, his moral puzzles do not end by passing judgment from a moralist perspective; they prompt us to search inward to assess the choices and behavior on display.

The Salesman follows Emad (Shahab Hosseini) and Rana (Taraneh Alidoosti), a married couple who, in the first scenes, must rush out of their apartment complex. A backhoe digging on the ground level has caused the building to quake, leaving massive cracks in the structure and inside their home. Already the film has taken on symbolism, hinting that actions have unexpected consequences. Emad and Rana look for another apartment, and their coworker Babak (Babak Karimi) suggests a place. The former tenant, a single mother with a young child, still has some items locked in a spare room, but otherwise, it’s an adequate living space—and they’re desperate. The childless Emad and Rana move in, despite the former tenant’s protests to Babak. All is well until one night when Rana is home alone and waiting for Emad to return with groceries, and the buzzer sounds. Rana remotely unlocks the gate and opens the apartment door for her husband. But instead of Emad, a man enters the apartment and attacks her in the shower, leaving Rana bloodied, traumatized, and unable to remember her attacker’s face. The details of what happened remain unclarified, but Emad assumes the worst.

While trying to understand what happened, Emad learns from neighbors that the former tenant had many male callers, and likely one of them arrived at the apartment expecting her but found Rana instead. However, Emad seems less concerned about Rana’s well-being and the lingering psychological effects that have crippled her emotions than servicing his sense of a husband’s justice. Farhadi’s script mentions in passing that such a crime would never warrant police attention, perhaps because it’s a crime against a woman in Iran’s stark patriarchal society. Emad resolves to pursue the matter himself after locating some keys and a phone left by the attacker, but in doing so, he fulfills an aggressive masculine stereotype. Eventually, he uncovers the likely culprit in an older man with a weak heart (Farid Sajjadi Hosseini), whom Emad arranges to confront and expose, in front of the man’s family no less. Doing so requires him to lock the man in a bathroom until the family can arrive. When Rana finds out what he has done, she threatens to end their marriage (“If you talk to his family, it’s over between us,” she warns). All the while, Farhadi immerses his audience in the proceedings so thoroughly that it’s difficult to tell the moment everything spiraled out of control.

While trying to understand what happened, Emad learns from neighbors that the former tenant had many male callers, and likely one of them arrived at the apartment expecting her but found Rana instead. However, Emad seems less concerned about Rana’s well-being and the lingering psychological effects that have crippled her emotions than servicing his sense of a husband’s justice. Farhadi’s script mentions in passing that such a crime would never warrant police attention, perhaps because it’s a crime against a woman in Iran’s stark patriarchal society. Emad resolves to pursue the matter himself after locating some keys and a phone left by the attacker, but in doing so, he fulfills an aggressive masculine stereotype. Eventually, he uncovers the likely culprit in an older man with a weak heart (Farid Sajjadi Hosseini), whom Emad arranges to confront and expose, in front of the man’s family no less. Doing so requires him to lock the man in a bathroom until the family can arrive. When Rana finds out what he has done, she threatens to end their marriage (“If you talk to his family, it’s over between us,” she warns). All the while, Farhadi immerses his audience in the proceedings so thoroughly that it’s difficult to tell the moment everything spiraled out of control.

The Salesman has been described as a thriller by some critics. And it certainly has elements of a thriller, with a seemingly righteous man hunting down the criminal who has done his family an injustice. This and other Farhadi works resemble those 1990s domestic thrillers, such as Single White Female or The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (both from 1992), except he goes deeper than Hollywood’s surfaces. Consider how Farhadi uses a classic of the American stage as a critical and ironic text. Both Emad and Rana serve as actors in their local theater company, mounting a production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. They perform the roles of Willy and Linda Loman, respectively, in a play about the quiet desperation of a family struggling for the good life. Emad, who also teaches literature to high-school students, understands how to read the meaning of a text, so how does he fail to see the link between the older man he cornered and Willy Loman? If he is a villain, he evokes more than a pang of sympathy in his similarities to Willy, especially when he humbly admits his vocation: “I sell clothes by the roadside in the evening.” Does Emad dissociate the two because the play is fiction, and Emad’s life is real (at least in the world of the film)? Or has Emad’s masculine need for retribution blinded him to the parallels?

In a way, Farhadi’s films, including The Salesman, function as moral fables. Remember the story about Emad and Rana, someone might say. What is the lesson they learned? The story can be taken apart and pieced back together from a moral standpoint in many ways, functioning like a social prompt designed to create a critical curiosity about class, gender, and power in contemporary Iranian society. The film’s mise-en-scène occupies a realistic mode of handheld camerawork by Hossein Jafarian and urgent editing. Even so, it occasionally gives way to stagelike lighting and locations that resemble the theater production of Death of a Salesman. Note the pivotal scenes in Emad and Rana’s abandoned former apartment complex, how the stark lighting and empty spaces serve as a stage. A grand drama plays out inside of these rooms, not only from Emad’s unwillingness to back down despite Rana’s pleas but when the old man’s family arrives and his seemingly impulsive act (“Forgive me, I was tempted,” he confesses) becomes the pathetic admission of a defeated human being. Rana sees the humanity of her attacker, but can Emad? Does the old man deserve Emad and especially Rana’s forgiveness? Hosseini’s performance contains a seemingly grounded sense of the world until his character’s hunger for vengeance consumes him. Both Hosseini and Alidoosti, having worked with Farhadi before on About Elly (2009), give astounding performances that never overplay how their subtle shifts in perspective inform the morality tale at the film’s center.

When The Salesman debuted in 2016, Farhadi was perhaps the most widely celebrated Iranian filmmaker apart from Abbas Kiarostami. His 2011 film, A Separation, won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, prompting his earlier films, such as About Elly, to earn distribution in the US. Today, his series of domestic dramas and thrillers have a regular place in the arthouse circuit. The Salesman is among Farhadi’s most renowned pictures, having won prizes for Best Actor (for Shahab Hosseini) and Best Screenplay at the Cannes Film Festival, and later the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. But when the Trump administration signed a racially targeted executive order in January 2017, commonly known as the “Muslin ban,” Farhadi and Alidoosti boycotted the Academy Awards ceremony scheduled for late February 2017. When Farhadi’s film won the Oscar, Anousheh Ansari, an Iranian-American engineer and space tourist, accepted the award and read his speech decrying the “inhumane” policy. For a filmmaker who has fought censorship in his own country, Farhadi must have seen the boycott as an affront to the message of his film.

When The Salesman debuted in 2016, Farhadi was perhaps the most widely celebrated Iranian filmmaker apart from Abbas Kiarostami. His 2011 film, A Separation, won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, prompting his earlier films, such as About Elly, to earn distribution in the US. Today, his series of domestic dramas and thrillers have a regular place in the arthouse circuit. The Salesman is among Farhadi’s most renowned pictures, having won prizes for Best Actor (for Shahab Hosseini) and Best Screenplay at the Cannes Film Festival, and later the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. But when the Trump administration signed a racially targeted executive order in January 2017, commonly known as the “Muslin ban,” Farhadi and Alidoosti boycotted the Academy Awards ceremony scheduled for late February 2017. When Farhadi’s film won the Oscar, Anousheh Ansari, an Iranian-American engineer and space tourist, accepted the award and read his speech decrying the “inhumane” policy. For a filmmaker who has fought censorship in his own country, Farhadi must have seen the boycott as an affront to the message of his film.

To look upon people with the individual attention and empathy they deserve forms one of The Salesman’s major themes. In a brief scene early in the film, Emad shares a taxi. A woman seated next to him in the back asks the cab to stop; she doesn’t want to sit next to Emad. Later, Emad’s student, who was also sharing the taxi, asks his teacher about the woman’s behavior. Emad reasons, “Someone behaved badly to that lady in a taxi, and now she thinks they’re all the same.” He does not take offense to her behavior but understands her reaction to judge a group for one individual’s crime—to a point. The question remains: Does Emad recognize that the woman’s fear derives from her relegated role as a woman in Iranian society? Even though he remains aware of humanity’s tendency to judge groups of people (by race, gender, sexuality, etc.), Emad seems oblivious to his privilege. Furthermore, he acts on his dominant role in the culture by pursuing vengeance, even after Rana pardons the attacker. When she tries to stop him, he tells her “Don’t interfere” with a superior tone. In this way, he’s both aware of dangerous generalizations and fulfilling them.

Farhadi’s characters inhabit a story that forces questions about masculinity in Iranian culture and hopes that audiences can see beyond assumptions to recognize that a common ground extends to every human being. However, The Salesman does not depict any such universal similarities, only the problems that keep people from identifying with one another. To be sure, Farhadi offers more questions than answers, but he never resorts to didacticism, which may be why many mistake the film for a thriller. His treatment of the social and psychological puzzle is subtle, never sacrificing dramatic involvement for his Socratic method of asking questions through storytelling. Indeed, The Salesman is crafted with the precision of a great dramatist who effortlessly weaves form and content into a story that, while set in modern-day Iran, could take place anywhere.

(Note: This review was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on April 28, 2022.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review