The Running Man

By Brian Eggert |

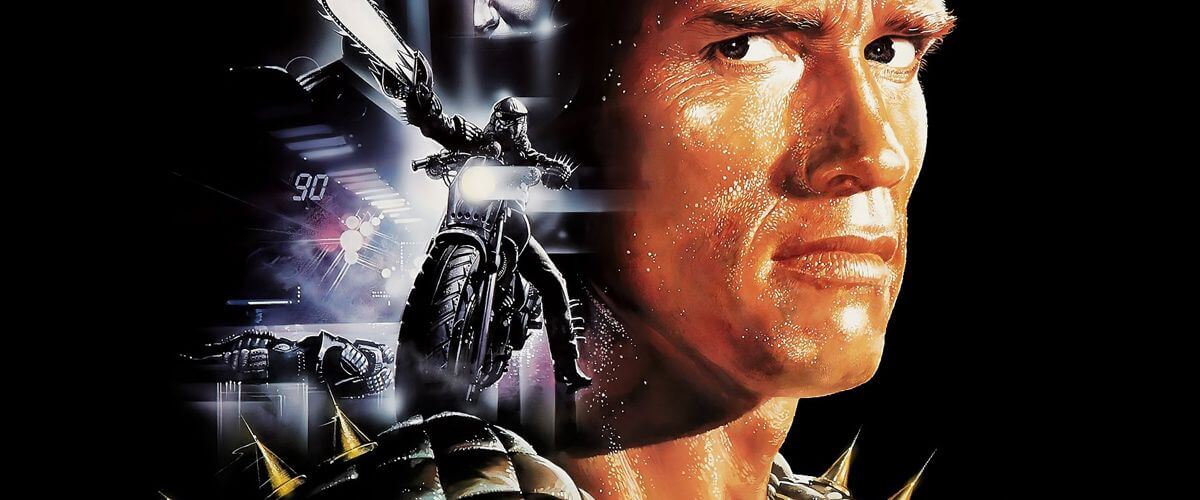

At one point in The Running Man, Arnold Schwarzenegger grabs some random goon by the genitals, looks straight into his eyes with a snarky grin, twists, and says, “Give you a lift?” He then lifts said goon over his head and throws the poor guy over a platform to his death. And that’s about as sophisticated as this Stephen King (writing as Richard Bachman) adaptation gets, being about a televised gameshow of the future in which, to win their own freedom, convicted criminals face hunter-killers called “Stalkers” in an arena. The film by director Paul Michael Glaser (better known as Starsky from TV’s Starsky and Hutch) amounts to a cinematic gladiatorial exhibition—complete with a cast of bodybuilders, boxers, and professional wrestlers—with touches of a cynical post-apocalyptic dystopia to decorate the scenery. At odds with its own purpose, the movie condemns the exhibition of violence, and yet at every turn resolves to be the very thing it condemns.

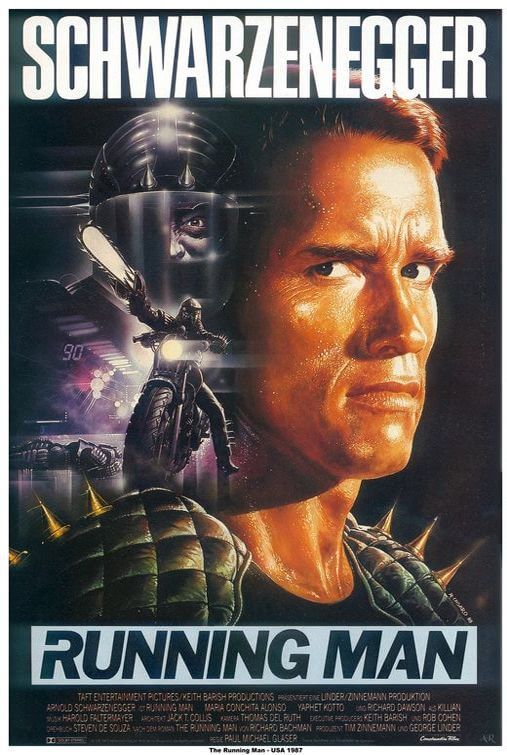

By 1987, when the movie was released, Schwarzenegger had become a household name thanks to Conan the Barbarian, The Terminator, and Predator. Fans of King’s book should have thrown out any hope for a faithful translation as soon as Schwarzenegger signed to star. The protagonist of King’s book, Ben Richards, was a gaunt man vying to save his daughter from disease and his wife from debauchery when he reluctantly agrees to participate in the titular game show, which pays its volunteer contestants. Screenwriter Steven E. de Souza, who also wrote Schwarzenegger’s Commando, changed the story to suit Schwarzenegger’s macho, muscle-flexing needs but also reformatted the setting into a totalitarian rule. Schwarzenegger’s Richards becomes a military man framed by a corrupt government, who then escapes imprisonment with his friends Laughlin (Yaphet Kotto) and Weiss (Marvin J. McIntyre) only to be captured and forced on a government-funded gameshow called “The Running Man,” hosted by beloved personality Damian Killian (TV’s Richard Dawson). As the poster’s tagline reads: “It is the year 2019. “The Running Man” is a deadly game no one has ever survived. But… Schwarzenegger has yet to play.”

Just before he’s launched into the arena with his friends, Richards comes face-to-face with Killian, and Schwarzenegger (shamefully) threatens, “I’ll be back,” just in case you forgot how badass that line was when you first saw it in The Terminator, or in the half-dozen other movies in which he says that line. Anyway, once Richards and Co. land in the danger zone, Killian asks an audience member to pick the first Stalker, one of several elaborately dressed, annoyingly themed villains that Ah-nuld makes short work of: former WWF star Professor Toru Tanaka plays Sub-Zero, who zips around on ice skates, slap-shots explosive pucks, and swings his bladed hockey stick; brutish Gus Rethwisch plays Buzzsaw, a chainsaw-themed baddie on a dirtbike; Olympic wrestler Erland van Lidth plays Dynamo, a lightbulb-suited fat man that shoots electric bolts; boxer Jim Brown plays a flamethrower-wielding Stalker called Fireball; wrestler Jesse Ventura is Captain Freedom, whose America garb seems contrary to the movie’s dystopian worldview; bodybuilder Sven-Ole Thorsen appears as Killian’s bodyguard.

As you can see, it’s all very kitschy and obvious, as Schwarzenegger goes from one opponent to the next, pummeling them in various horrible ways and taking the utmost pleasure in every death he causes. Though Richards was framed for the massacre of innocent women and children, he has no qualms about shoving a chainsaw up Buzzsaw’s groin or stomping in Dynamo’s face. After each killing, Richards turns to the show’s camera, as if addressing Killian, and utters any number of silly one-liners: “Hey, Killian! Here’s Subzero! Now… plain zero!” A line like this is so stupid one wonders if Schwarzenegger improvised it himself and no one on set had the heart (or guts) to tell him how dim it sounded. Oh, and what happened to Buzzsaw? “He had to split.” Actually, he didn’t go anywhere, Arnold, he’s right there where you left him, on the floor in two pieces. Curiously enough, though his cohorts seek to bring down the government’s signal so they can broadcast their rebel message, Richards seems more intent on putting on a good show. Killian’s audience begins cheering for Richards instead of the Stalkers, thus allowing the movie’s audience to cheer along. By the end, if you buy into this violent gameshow-of-a-movie, you’ve become just as bad as the bloodthirsty crowds that are portrayed as mindless, uninformed hordes.

As you can see, it’s all very kitschy and obvious, as Schwarzenegger goes from one opponent to the next, pummeling them in various horrible ways and taking the utmost pleasure in every death he causes. Though Richards was framed for the massacre of innocent women and children, he has no qualms about shoving a chainsaw up Buzzsaw’s groin or stomping in Dynamo’s face. After each killing, Richards turns to the show’s camera, as if addressing Killian, and utters any number of silly one-liners: “Hey, Killian! Here’s Subzero! Now… plain zero!” A line like this is so stupid one wonders if Schwarzenegger improvised it himself and no one on set had the heart (or guts) to tell him how dim it sounded. Oh, and what happened to Buzzsaw? “He had to split.” Actually, he didn’t go anywhere, Arnold, he’s right there where you left him, on the floor in two pieces. Curiously enough, though his cohorts seek to bring down the government’s signal so they can broadcast their rebel message, Richards seems more intent on putting on a good show. Killian’s audience begins cheering for Richards instead of the Stalkers, thus allowing the movie’s audience to cheer along. By the end, if you buy into this violent gameshow-of-a-movie, you’ve become just as bad as the bloodthirsty crowds that are portrayed as mindless, uninformed hordes.

Perhaps because, as I write this, Gary Ross’ version of Susanne Collins’ The Hunger Games—a tale about children forced to fight to the death in televised combat for a totalitarian government—is due in theaters soon, and so, having just finished the trilogy of books, I am forced to consider how similar these stories are, and thus how one-note The Running Man proves to be in contrast. Collins does such an exemplary job of reflecting on the psychological and physical ramifications of being put through hell for the entertainment of an oppressive world, that one cannot help but find this movie such a dull experience, so amazingly one-note in its raison d’être, which is to provide entertainment for cheering crowds of kill-hungry viewers. When all Richards has to do in the finale is flex his muscle, quip another one-liner, and kiss his resident damsel Maria Conchita Alonso, it’s disappointing that the filmmakers didn’t explore the greater themes otherwise present in King’s source material.

Then again, perhaps this assessment is not fair. Defenders might argue that the movie’s “just an action flick” and one from the 1980s no less—an era ruled by cornball action fodder from screen heroes like Schwarzenegger and Stallone. Muscles prevail over brains at every turn, and to hope for more is, unquestionably, missing the point. Here’s a movie where Hollywood has lined up a smorgasbord of beefy heroes and villains to slaughter each other for our entertainment, and I’m questioning the morality of it. How dare I? Nevertheless, The Running Man equates its gameshow to the Roman Colosseum, where unruly masses are controlled and settled by the government’s willingness to put on a spectacle, while the anti-establishment protagonists—rather like Ridley Scott’s Gladiator—seek to bring the show down. Only, in Gladiator, Russell Crowe fought every staged battle to survive and avenge his family, to protect Rome, whereas Schwarzenegger’s Ben Richards takes a little too much pleasure in committing excessive acts of violence.

The Running Man and everyone involved in the film-making seem more concerned with spectacle than with a plot rooted in thwarting The Powers That Be. Never once does Richards refuse to fight or rebel against the TV show—he’s not even particularly interested in the rebels’ mission. He’s a motivation-less hero and a killing machine. We’re never truly meant to find the violence deplorable or sickening, though it is; instead, we’re supposed to clamor along with Killian’s brainless fanbase as they win door prizes, like “The Running Man Home Game.” Incidentally, a computer game based on The Running Man was released in the late 1980s. What’s so offensive about this movie is how little respect it has for its audience. It aligns the moviegoer with Killian’s crowds, portrays gory acts for our entertainment, and ultimately sends mixed messages about how we’re supposed to feel about what’s onscreen. But hey, it’s just an action flick.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review