Reader's Choice

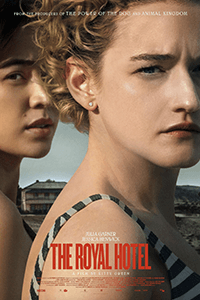

The Royal Hotel

By Brian Eggert |

Every few years, a new movie warns us about the perilous conditions and dangerous people in the Australian outback. Most famously, Ted Kotcheff’s Wake in Fright (1971) finds a young British schoolteacher corrupted by hard-drinking locals into abhorrent behavior, including a revolting kangaroo hunt sequence. That same year, Nicolas Roeg’s masterful Walkabout considered Nature’s sublimity in the outback, though he made domesticity look even more treacherous. Elsewhere, it’s a location inhabited by backwoods psychopaths, such as the one in Greg McLean’s Wolf Creek (2005). But more often than not, filmmakers from George Miller (the Mad Max series) to David Michôd (The Rover, 2014) depict the hardened nature of the sun-baked terrain as post-apocalyptic, equating the dusty and unforgiving environment to what the movies would have us believe are its equally uncivilized inhabitants. Of course, this cinematic myth unfairly characterizes the outback and a segment of Australian culture.

Then again, in the case of Australian filmmaker Kitty Green’s The Royal Hotel—a thriller about two female backpackers on a work-for-travel program, who accept an ill-advised job in an isolated mining town bar where they’re ogled and harassed by the boozy locals—there’s some truth to it. Green, working alongside co-writer Oscar Redding, based her scenario on Pete Gleeson’s 2017 documentary, Hotel Coolgardie. Gleeson’s fly-on-a-wall style captures what happens when two young Finnish women work behind the bar in a small Australian town. Even with Gleeson’s cameras on, the locals engage in discrimination, lewd insults, and unwanted sexual advances toward the two women, making one wonder what might’ve occurred had the cameras been off. It’s a disturbing watch, and Green dramatizes those events. She replicates the bar’s layout and borrows dialogue verbatim, delivering a tense experience that imagines a heightened version of the doc with a fanciful catharsis in the end.

The film opens with two vacationing Americans, Hanna (Julia Garner) and Liv (Jessica Henwick), running out of money and reluctantly accepting bartender gigs, for which they must be willing to deal with “a little male attention.” Unfazed, they quickly realize upon their arrival that the caution was an understatement. The perpetually drunk owner, Billy (Hugo Weaving), calls Hanna a “smart cunt,” and the sign outside announces “Fresh Meat” with a crude chalk drawing of breasts underneath. The film alludes to Hanna and Liv seeking to escape some sort of trauma in the States with an international “adventure,” but they’re thrust into a world where unruly drinkers pile into the bar during evening hours, shout obscenities, and make crude passes. Hanna immediately wants to leave, attuned to the male sexual aggression on display, whereas Liv seems to compartmentalize what seem like clear warning signs.

The film opens with two vacationing Americans, Hanna (Julia Garner) and Liv (Jessica Henwick), running out of money and reluctantly accepting bartender gigs, for which they must be willing to deal with “a little male attention.” Unfazed, they quickly realize upon their arrival that the caution was an understatement. The perpetually drunk owner, Billy (Hugo Weaving), calls Hanna a “smart cunt,” and the sign outside announces “Fresh Meat” with a crude chalk drawing of breasts underneath. The film alludes to Hanna and Liv seeking to escape some sort of trauma in the States with an international “adventure,” but they’re thrust into a world where unruly drinkers pile into the bar during evening hours, shout obscenities, and make crude passes. Hanna immediately wants to leave, attuned to the male sexual aggression on display, whereas Liv seems to compartmentalize what seem like clear warning signs.

The Royal Hotel builds danger and suspense through what is obviously a bad situation from the start. Watching the film, the viewer grows frustrated with Liv, who apologizes for the behavior of the bar’s top creep, Dolly (Daniel Henshall). But then, Hanna is perhaps too quick to trust Matty (Toby Wallace), a younger bar patron whose smile disguises his dodgy behavior. Their willingness to remain at the bar evokes the same reaction as when you’re watching a horror movie, and someone decides to explore a strange noise in the dark basement with an unreliable flashlight. “Get out of there,” you want to shout at the screen. And while much of Green’s film draws from the documentary, The Royal Hotel invents the last third. The only other reliable woman, Carol (Ursula Yovich), the bar’s cook, takes Billy to the hospital after an accident, leaving Hanna and Liv alone, and the dynamic between the inebriated customers and the young bartenders escalates.

Similar to her work with Garner on 2020’s The Assistant, Green’s exposition is spare, and the characterizations prove thin. But where that minimalism served her previous feature, Green’s narrative vagaries leave unsatisfying questions here. Most nagging among them is Dolly and his intentions, which may be sexual and aggressive in nature, or they may extend to sex trafficking, depending on how you read his scenes. More subtle is how even the seemingly nice guys have predatory or groupthink tendencies. A quiet but muscular type, Teeth (James Frecheville) rescues the women in one scene, only to proclaim about Liv, “She’s mine!” Elsewhere, when a Norwegian traveler Hanna met at the beginning of the film comes to their rescue, he falls into toxic male camaraderie and joins in calling her a C-word. All of this might seem unlikely or a reductive portrait of Aussie men, until you remember Hotel Coolgardie, and how it’s not far from the truth of the real situation.

Shooting with the alternately sun-drenched and squalid color palette one might expect, cinematographer Michael Latham and Green apply a conventional thriller aesthetic to The Royal Hotel. The filmmaking looks inspired by titles such as Wake in Fright or Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971), where the sweaty throng of men and rapey backwoods types present a threat to modern young women. By the final scene, which adopts sociopolitical “burn it down” imagery, The Royal Hotel might prove a tad on the nose, but it’s always involving, despite its underdeveloped characters and simplistic situations. Of course, Green and Garner make an irresistible director-actor team, with Garner again lending her fierce presence to a seemingly diminutive role in which she ends up being an axe-wielding badass. Whatever the 90-minute feature lacks in dimension, it makes up for with an immersive and even horrifying situation told from a woman’s perspective.

(Note: This review was originally posted to Patreon on November 9, 2023.)

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review