The Rover

By Brian Eggert |

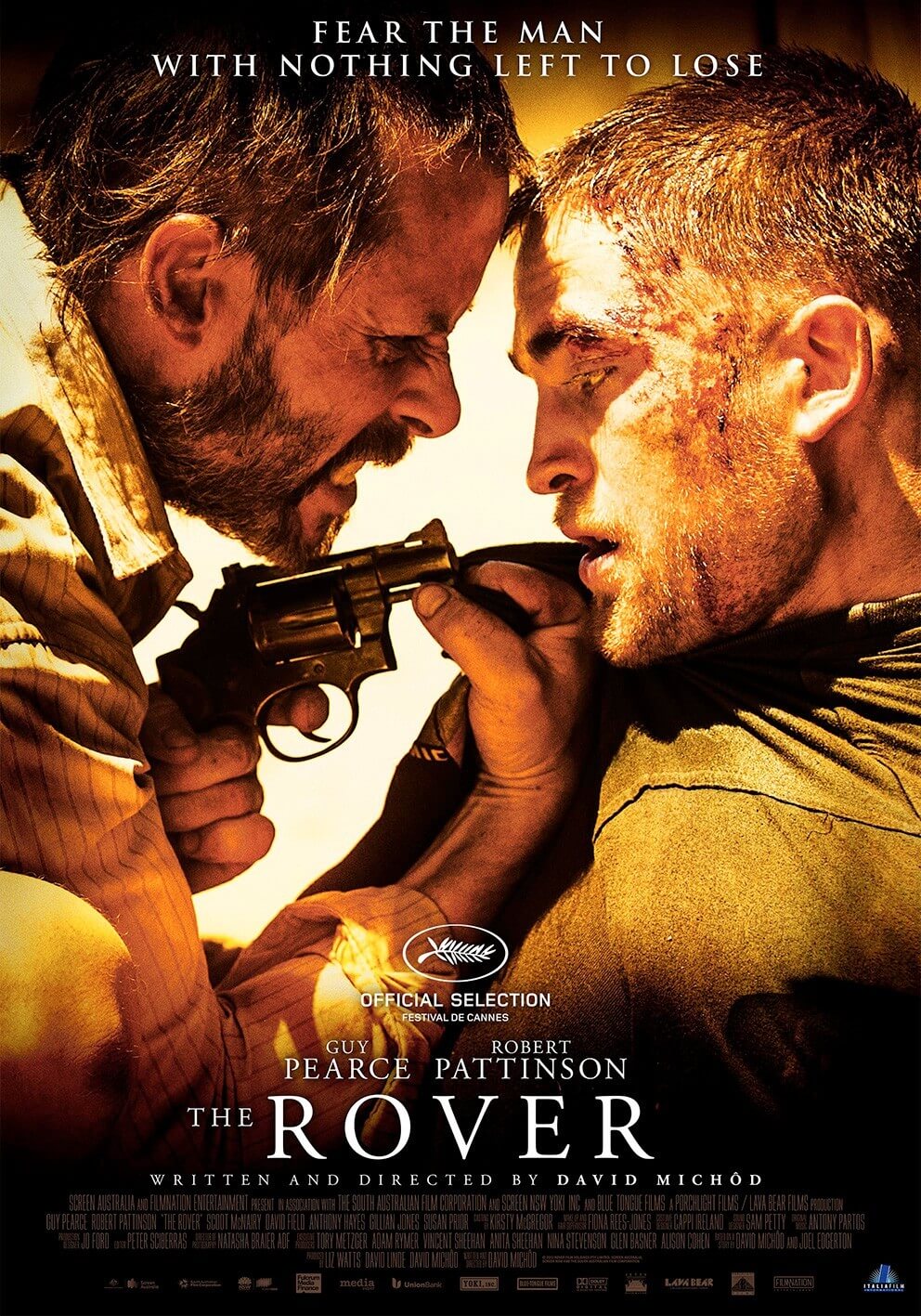

The Rover, Australian filmmaker David Michôd’s sophomore feature as writer-director after his 2010 crime saga debut Animal Kingdom, once again transforms the Australian landscape into an unforgiving post-apocalyptic wasteland. With obvious influence from Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and nods to George Miller’s Mad Max trilogy, Michôd’s second film makes use of an arid backdrop obscurely set “10 years after the collapse” to construct a familiar genre situation. Desperate, grubby characters behave in inhuman ways to scrape by, eking out whatever pathetic victories they can achieve through murder or other horribly violent acts, all to ensure their survival in a world suffering from a presumed economic disintegration. To be sure, audiences have been inundated with tales from after the downfall of society, most with more plot details than Michôd’s carefully restrained presentation and vague scenario offer. But the film’s tense grip and pristine technical approach latch onto the viewer early and don’t let go until the final, deeply rewarding scene.

A bearded, patchily-haired Guy Pearce plays a character named, according to the press release, Eric (although if his name is ever said in the film, this critic missed it). A grave man, Eric arrives at a dusty wayside stop, and like something out of a Western, he enters an Asian tavern for a solitary drink. Outside, a trio of panicky fugitives—the embittered Archie (David Field), driver Caleb (Tawanda Maryimo), and wounded Henry (Scoot McNairy)—have just escaped a shootout, and while arguing over why they left Henry’s brother behind, they flip their truck not far from Eric’s sedan. The three scramble, and in a frenzy, abandon their stuck vehicle and commandeer Eric’s car. Incensed, Eric has better luck dislodging their pickup and quickly pursues the three car thieves to retrieve his sedan. During the inevitable confrontation, Eric is outmatched and outgunned, but no less provoking and intent on recovering his car to an almost blindly self-destructive extreme.

Eric behaves as if he has nothing to lose and, searching for both his car and a place to buy a gun, with which he plans to confront the men who stole his car, fearlessly engages others who would no doubt kill him if he had anything to offer. Eric seems soulless, viciously carrying on down a literal and existential highway where stopping means a kind of spiritual death, both the actualization and the ironic opposite of a “death drive.” This much is understood when he stops in a small, decrepit town and finds a circus sideshow living in a rundown home. Its chillingly mannered caretaker, referred to as Grandma (Gillian Jones), tries to offer Eric the company of a young boy, and a little person loses his life when he strong-arms Eric over the price of a handgun. Elsewhere, those who’ve settled down seem washed out, as though every moment of their lives is spent in these dimly lit, garbage-strewn interiors, heaped over on some dilapidated mattress and deprived of any meaningful existence. Fascinatingly, Eric’s raison d’être remains curiously unknown. When Grandma asks Eric his name, he refuses to answer or explain when she asks why he wants his automobile back so much, and instead, persists with his own line of questioning.

Just as we’re asking those same questions ourselves, Eric finds a wounded young man, Rey (Robert Pattinson), Henry’s dimwitted brother, sniffing around the truck and looking for his gang. To keep Rey alive so he can show the way to Henry, and then his sedan, Eric takes Rey to a compassionate lady doctor (Susan Prior). At the doctor’s secluded home, our antihero pauses to regard kennels in which dogs are kept to prevent them from being eaten by humans; this seemingly insignificant scene has great bearing later on, and might be the defining clue to Eric’s humanity. On the road with Rey as a pseudo-hostage, Eric grows sympathetic to the cowardly innocent in a strain echoing the novelistic pages of John Steinbeck. Pattinson is outstanding as the near-helpless Rey, the resident Lennie Small, and gives layers to the Southern-American character through his endearingly weak portrayal. As Rey becomes a kind of loyal dog to Eric, and therein all the more meaningful, Pattinson never overacts scenes or character traits that could’ve easily become garish in another performer’s hands and, after Water for Elephants and Cosmopolis, takes another major step toward shedding his Twilight persona.

And while Michôd’s homage to the aforementioned post-apocalyptic staples remains evident, so too are other Australia-bound pictures where the bleak quality of the landscape eats away at its human inhabitants. Elder examples in Walkabout (1971) and Wake in Fright (1971) come to mind; Pearce himself starred in The Proposition in 2007 for John Hillcoat, a grueling Western set on an Outback even more punishing than the Wild West. Along with Pearce’s ragged presence in Ravenous (1999), the actor strangely looks at home with days of grime on his flesh and flies endlessly buzzing around his face. Pearce’s intensity never falters, yet he exudes a weary humanity under coats of sweat and dirt. Something about Eric’s merciless actions being delivered by Pearce permits the audience some glimmer of hope for understanding the character—and getting our entrenched questions about him answered. Like Charles Bronson’s gunslinger in Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), the story hints at the character’s backstory in a late scene, but without Sergio Leone’s attributed grandiosity. Michôd’s script, written from an idea he conceived with Joel Edgerton, represses any ostentatious revelations and contains just enough input to make Eric an intriguing mystery.

Refreshingly shot on film by cinematographer Natasha Braier, The Rover‘s presentation looks gorgeous and trance-like in its long, measured shots of dilapidated towns, purple-hued skies at dusk, and barren countryside. Further contributing to our hypnotic immersion, Aussie composer Antony Partos teamed with sound designer Sam Petty to construct evocative music of haunting electronic sounds and tempos aurally fused with the picture, save for one scene where pop music plays over a comically sweet moment to develop Rey’s vulnerability. Throughout, Michôd’s direction is masterful, his containment of the plot and what might’ve been too many unnecessary details are circumscribed down to an efficient, tight-wound minimalism that pays off in a surprisingly delicate way. Some may find the ending elusive, or the entire structure of The Rover aimlessly wandering throughout an underdeveloped setting. But upon reflection on the work as a whole, the viewer will find a carefully structured picture designed to manipulate our thinking that this film is a bleak downer devoid of humanity, whereas the answers to our questions about the source of Eric’s compassion are waiting to be discovered in the trunk of his car.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review