The Room Next Door

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published on DFR’s Patreon on December 5, 2024.

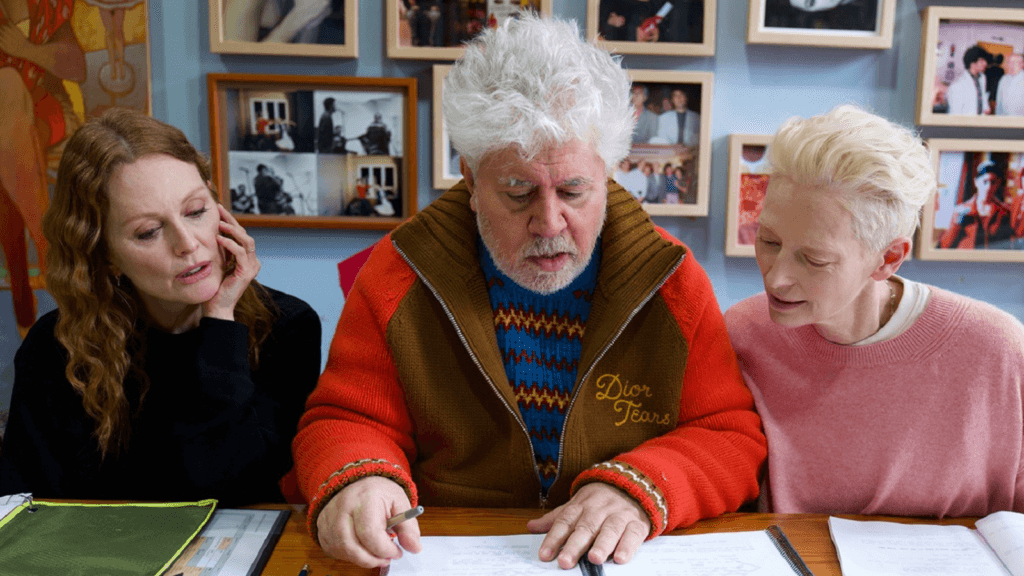

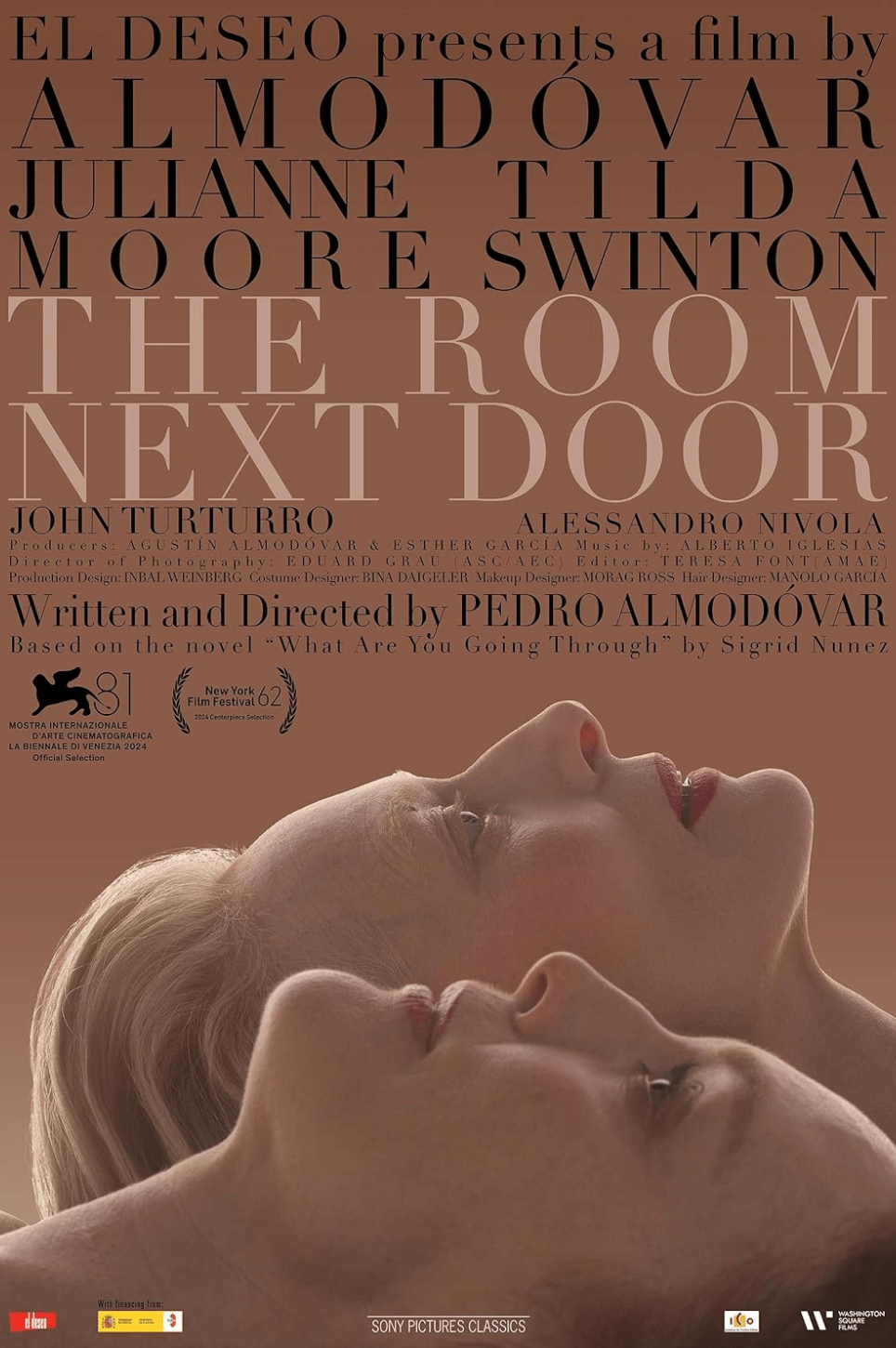

Few credits are more reassuring to this critic than “A Film by Almodóvar.” The Spanish auteur makes his English-language debut with The Room Next Door, a quiet, somber work of reflective tenderness, presenting a stark contrast to, albeit with no less color than, his otherwise signature bursts of melodrama and humor. Despite some superficial differences, his latest film adheres to what audiences associate with his distinct brand of filmmaking and storytelling. Almodóvar’s tale involves complex emotions and backstories, giving way to flashbacks that recontextualize the present, weaving an elaborate narrative structure that embraces deep feeling and rewards intellectualization. Like most Pedro Almodóvar films, there’s a harmony here between the aesthetic, emotional, and cerebral, allowing its pleasures to be that much more enriching. And what pleasures, from two carefully calibrated performances by his leads, Tilda Swinton and Julianne Moore, to the relatable outpouring of existential dread that feels so vital at this moment in time. The Room Next Door is a delicate, deeply felt film about friendship and death, and another of Almodóvar’s late-career films about taking stock of one’s life.

Based on the 2020 novel What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez, the film follows Ingrid (Moore), an author who just published her latest book. She learns that her longtime friend, Martha (Swinton), a former war correspondent for The New York Times whom she hasn’t spoken to in years, is dying from inoperable Stage 3 cervical cancer. Ingrid visits Martha at the hospital, and the two reconnect, realizing how much they’ve missed each other’s company. Martha has been undergoing experimental treatments, but she finds their existence almost disappointing; she had all but prepared herself for The End. Still, Ingrid and Martha share meals, shop in bookstores, and see movies together—the moments that fill a life. Eventually, Martha asks Ingrid to join her at a vacation house near Woodstock, NY, where she will live out her final days before taking a euthanasia pill she acquired illegally. Ingrid needs only to be there, sleep in the room next door, and, when the time comes, report her death.

Even in English, the setup recalls several other Almodóvar films, such as Talk to Her (2002) and Julieta (2016), in its tone and themes. The director cut his teeth in English-language filmmaking with two recent 30-minute short films. With The Human Voice (2020), based on the play by Jean Cocteau, the director first paired with Swinton for a surreal story highlighting his formal bravado, along with themes that weigh genuine emotions next to manufactured façades. Last year, Almodóvar unveiled Strange Way of Life, his queer Western starring Ethan Hawke and Pedro Pascal, inspired by the aesthetic of Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar (1954), a favorite of the director. In both, he went big, wielding bold stylistic flourishes and dramatic touches that could only be called Almodóvarian. Maybe that’s why The Room Next Door feels softened by contrast. This is a far more nuanced and meditative film, with characters who have perspective on their lives, how they’ve changed, what lessons they’ve learned, and how the world has warped around them.

To be sure, much of The Room Next Door involves realistic scenes of two seasoned friends talking about old lovers, friendships, experiences, and professional limitations. Ingrid listens as Martha shares details from her past that, given her recent relationship with mortality, have rekindled in her mind. She recalls Fred (Alex Høgh Andersen), an early lover who, upon returning from the Vietnam War, got her pregnant, left to work in a hospital, and died in a fire. Michelle, their daughter, has always blamed Martha for Fred’s absence in her life. Martha talks about her time covering wars in Iraq and Bosnia, and they laugh over sharing the same lover, Damian (John Turturro). When Martha finally asks Ingrid to be there when she dies, she admits that Ingrid wasn’t her first choice. Three other, closer friends declined. Regardless, they go to an “unknown place” upstate for Martha; somewhere she won’t be tempted to feel nostalgic about life—a modernist house resembling metal cubes with vast windows dropped into a forest landscape.

Although most of the film’s city sequences were filmed in New York, Almodóvar shot the house scenes in Madrid at Casa Szoke, a brutalist structure on Mount Abantos, nestled in the La Herrería Forest. Designed by María José Aranguren López and José González Gallegos’ architectural firm, the house remains Almodóvar’s most expressive flourish. The setting gives his cinematographer Edu Grau, in their first collaboration (the director’s usual d.p., José Luis Alcaine, retired), geometric frames and natural angles to heighten the otherwise quiet drama unfolding onscreen. Few filmmakers are so attuned to design and spaces as Almodóvar. While less visually pointed than his other films, The Room Next Door boasts a touch of artificiality, lavishness, and expressivity with Bina Daigeler’s lovely costumes and Inbal Weinberg’s attention to the production design. The film is rich with muted colors accented by bright artwork and primary-colored props, most of them from the director’s personal collection. Only compared to Almodóvar’s other, more vivid films does this one seem less striking.

Once again, Alberto Iglesias, Almodóvar’s frequent composer since the 1990s, supplies a score that sounds like it’s playing against a brooding conspiracy thriller. But The Room Next Door maintains a thoughtful tone, not only when considering Martha’s situation but also when Ingrid and Damien meet. Turturro plays an intellectual who, long ago, delighted both Ingrid and Martha with his superb lovemaking. Now, he sees the world in “death throes” from climate change and extremist ideologies. “I’ve completely lost faith in people doing the right thing,” he admits. At 75, Almodóvar no doubt shares some of this worldview. He survived Francoism and thrived in the liberal outpouring that followed, only to see far-right ideologies once more take power today. Late in the film, Alessandro Nivola appears as a self-described radical and god-fearing cop who investigates Ingrid after Martha’s death. The sanctimonious cop feels like a character from one of Almodóvar’s earlier films designed to unpack the oppression and consequences of Franco’s right-wing religious conservatism. At one point, a character remarks, “This world is absurd and inhumane, and I don’t see it improving anytime soon.” Almodóvar almost certainly agrees.

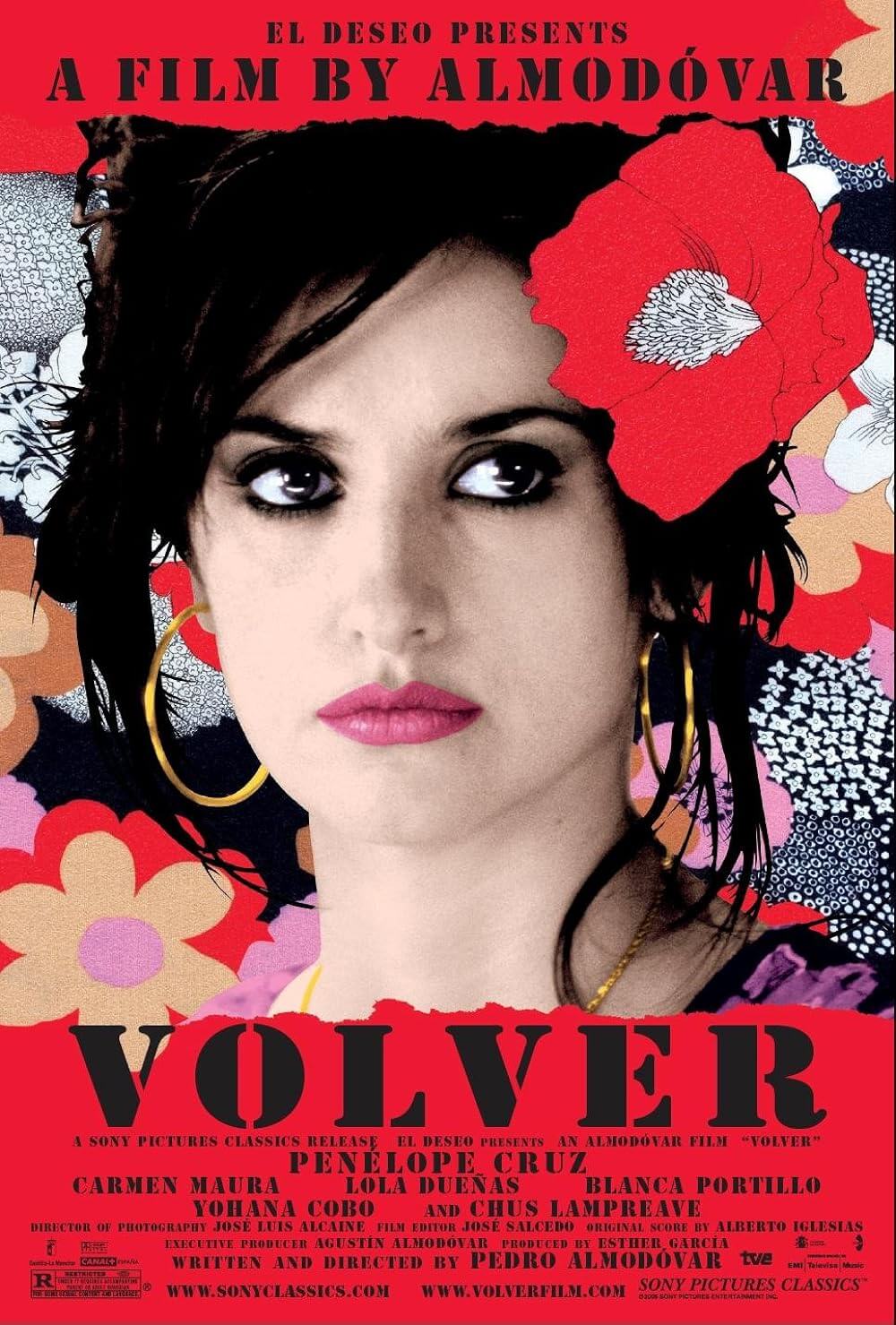

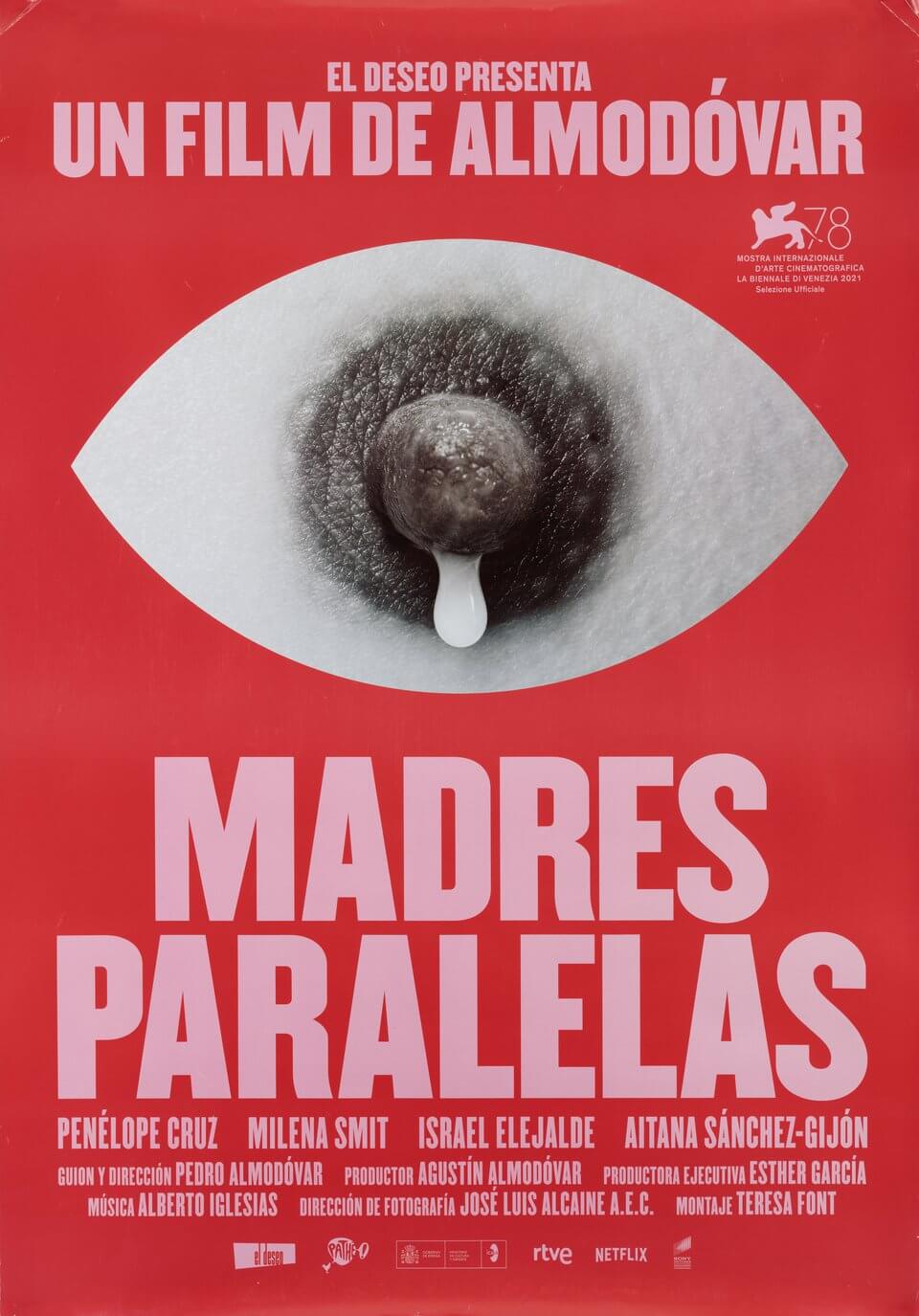

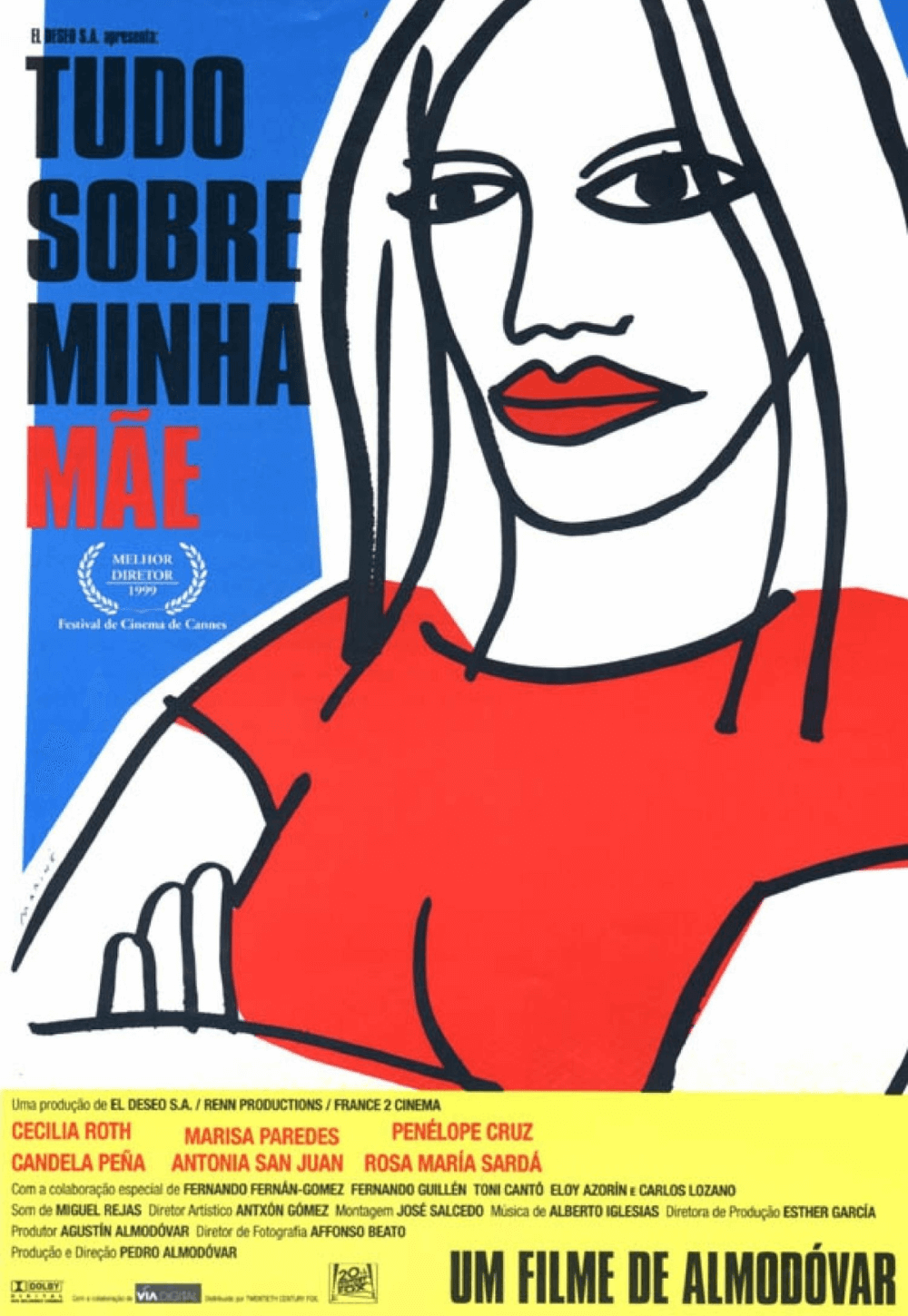

Of course, few have directed women with as much attention and understanding as Almodóvar. He belongs on a shortlist with George Cuckor, Sofia Coppola, Ingmar Bergman, Chantal Akerman, Woody Allen, and Lars von Trier of filmmakers who have been associated with layered female characters and accompanying performances. While Carmen Maura and Penélope Cruz have been his muses in the past, Moore and Swinton shine here. Swinton, who gives two performances after Michelle appears following her mother’s death, allows Martha to be prickly and sometimes inconsiderate of her friend. Looking hollowed out, she performs lines such as “I have practically held death in my hands; I never imagined it would be something so light” with a wounded, knowing quality that makes her disappear into the role. Similarly, Moore’s performance may feel low-key, but her lines, in particular the last few notes of the film, have a poetic cadence that conclude the film with devastating melancholy.

Every Pedro Almodóvar film is an event. He’s had so few underwhelming films in his impressive career, and those that disappoint only do so compared to the astounding heights of his other work. Some critics have unduly labeled The Room Next Door as a lesser film for him, and after the first half, I might have agreed. But the film has a way of sneaking up on the viewer, from its two rich, refined performances to its shared anxieties about the world and how passing might come as a relief. In the last half, the film finds Ingrid and Martha watching movies together. They settle on John Huston’s final work, The Dead (1987), an adaptation of the James Joyce novel. Both Almodóvar’s film and Huston’s end with contemplative remarks about death, expressed against the delicate fall of snow. The Room Next Door is full of tender, wounded passages that have an overwhelming effect, reminding us of Almodóvar’s masterful ability to turn delicate moments into poetry that stays with you long afterward.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review