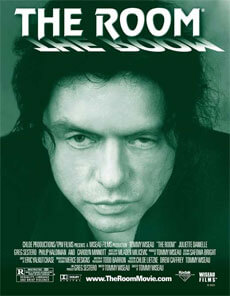

The Room

By Brian Eggert |

Most cult films transgress typical notions what we consider good and bad taste; they operate on another level entirely. Cult films usually have a rebellious streak, defying genre boundaries by blending established regimes in unlikely ways. They’re frequently morbid, triggering the audience’s reactions through excessive gore, sexuality, or otherwise unconventional material. They often deliver politically subversive commentaries to embolden counter-cultural viewership as well. And this, in part, is why communities of devoted viewers flock to repeated midnight madness screenings or buy countless home video editions of their favorite cult film—initiating titles like The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) or Eraserhead (1977) into an alternative canon. Tommy Wiseau’s The Room is exceptional because it contains none of these usual qualities of a cult film, apart from its rampant, enthusiastic following. There are no space aliens or scenes of gory excess. The sexuality is rather tame, albeit frequent and droning. And you would be hard-pressed to decipher any transgressive thematic message from the inane, often nonsensical dialogue and narrative.

The Room‘s cult status is predicated on how awful it is. There’s an active celebration of its badness, complete with ritualized viewing trends and a communal organization built around mocking it. Released in 2003, the independently produced film premiered in Los Angeles, where it received harsh reviews from those few who reviewed it. After two weeks, the film was a financial disaster, having flopped with just $1,800 in box-office receipts for a production with a shockingly high price tag of $6 million (the production looks like it was filmed with a household camcorder in 1992). But at the same time, a small segment of viewers couldn’t believe their eyes or adequately describe to their friends just how hilariously terrible it was. Within a year, those who had seen The Room began demanding additional exhibitions. Before long, midnight madness screenings emerged all over the country, with audiences throwing things at the screen or shouting quips, creating their own live version of Mystery Science Theater 3000.

The Room‘s following closely mirrors the ironic viewing of Ed Wood’s Plan 9 from Outer Space (1959), in that both Wiseau and Wood’s films have been called “the worst movie ever made.” Both have a curious anatomy; their methods of form and narrative seem to exist on another planet, and their directorial ineptitude removes any hope of relating to their story, characters, or experiencing their intended reaction. And yet, the filmmakers instill a contagious enthusiasm into their work. Wiseau and Wood both pour their heart and soul onto the screen with a profound inability to articulate their feelings in any intelligible way that other human beings might understand. To be sure, The Room‘s so-bad-it’s-good aesthetic, along with the film’s hilariously misguided sex scenes and attempts at sincerity, result in a camp quality. For Wiseau, who serves as writer, producer, and (contested) director, his film has an ineffable formality that operates in the name of good taste but, quite unintentionally so, achieves a laughable outrageousness.

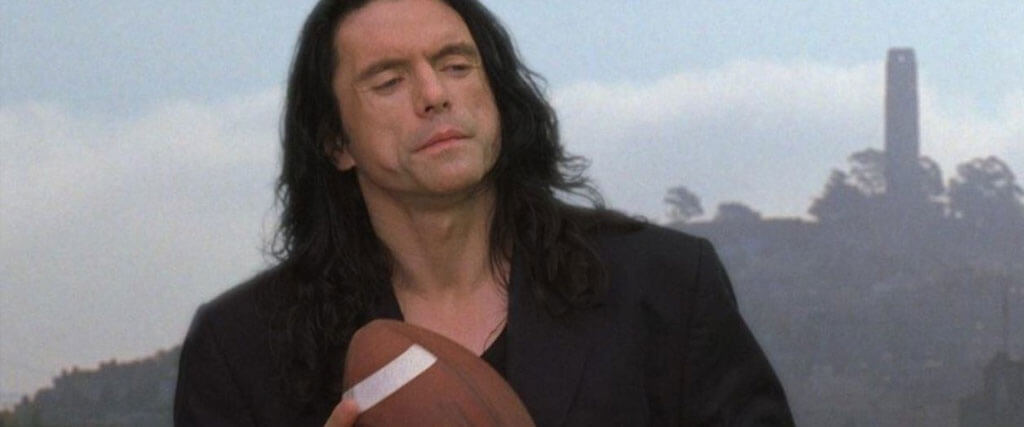

The plot follows Johnny (Wiseau, looking like a death metal bandleader just out of rehab), a successful banker who loves Lisa (Juliette Danielle), his “future wife” (the word “fiancée” is not in Wiseau’s vocabulary). Lisa, always dissatisfied and conniving, tries to manipulate Johnny into hitting her so she’ll have a reason to leave him. At the same time, she cheats on him with Mark (Greg Sestero), Johnny’s best friend. And that’s about the extent of it. On the periphery, Johnny and Lisa serve as makeshift parents to Denny (Philip Haldiman), a boy from next door in his late twenties. Denny, a creeper who not-so-secretly loves Lisa, has a pronounced desire to watch Johnny and Lisa make love. And make love they do (in the naval, apparently), about every 5-to-10 minutes in the film. Elsewhere, Johnny’s goof-faced friend Mike has underwear trouble, Denny discover’s drugs, Johnny plays wiretapper, and Lisa’s mother learns she has breast cancer—all plot points that are dismissed almost as quickly as they’re introduced.

At one point near the finale, after Johnny grinds on Lisa’s dress before tragically shooting himself, Mark finally tells Lisa, “As far as I’m concerned, you can drop off the Earth. That’s a promise.” Every scene in The Room makes about as much sense as that line. Even when the viewer can actually make out what Wiseau or his cast is talking about, it still fails to make any sense. The writing sounds as though a glitchy, 16-bit robot was fed hundreds of soap opera scripts, and then asked to come up with its own screenplay. The outcome is repetitive, illogical, and often beyond all reason. Most exchanges begin with “Oh, hi,” most transitions are marked by “Anyway,” and most conversations end with either “Don’t worry about it”—or Lisa’s frequent line, “I don’t want to talk about it.” The other-worldly quality of the dialogue is only matched by Wiseau’s cornball character descriptions. For instance, whenever Wiseau depicts male bonding, he shows men playing a catch with a football or talking about their inability to understand women. The incoherence of everything onscreen, and the lack of connective tissue from one scene to the next, make the proceedings compulsively watchable.

Wiseau’s formal approach does not correlate with the considerable amount he spent on cameras and filmmaking equipment; instead, the look proves only that Wiseau had no idea how to make a film. Shooting in alleyways and cramped sets, which sometimes took the place of actual locations nearby, the production has the look of an eighties sitcom (in fact, most scenes have a softness that suggests cheap processing, unfocused cameras, or just altogether lousy craftsmanship). Additionally, according to Sestero’s 2013 book, The Disaster Artist: My Life Inside The Room, the Greatest Bad Movie Ever Made, Wiseau failed to obtain the necessary permits to shoot outdoors in San Francisco. Rather than just acquire the permits, the film’s numerous rooftop scenes were achieved with an embarassing green-screen effect to digitally render a San Francisco backdrop—an effect that appears to have cost about $12 to animate. The sensory assault also extends from the visual to the aural, with several R&B tracks that mirror the worst of 1990s slow jams being placed over the very long, very unsexy, and very awkward sex scenes.

The film’s following has some less charming qualities—such as the mostly young, male hipsters who maintain the fandom for The Room and ignore or laugh-away some of the film’s more disturbing overtones. Wiseau’s self-pitying character, reportedly based on his own experiences, maintains a disturbingly low view of women as manipulative, unfaithful, lazy, gold-digging, and always sexualized. Female characters are either “babes” or “bitches” in Johnny’s view, whereas Mark observes, “Oh man, I just can’t figure women out. Sometimes they’re just too smart. Sometimes they’re just flat-out stupid. Other times they’re just evil.” (Smart, stupid, evil—the three potential states of a woman, according to the Book of Mark.) Along with Wiseau’s rather slimy use of soft-core sex scenes that seem to carry on forever, there’s a debauched undercurrent to the film’s treatment of women, one made even pervier given the film’s pretense of a pseudo-wholesome and emotionally profound melodrama.

The film’s following has some less charming qualities—such as the mostly young, male hipsters who maintain the fandom for The Room and ignore or laugh-away some of the film’s more disturbing overtones. Wiseau’s self-pitying character, reportedly based on his own experiences, maintains a disturbingly low view of women as manipulative, unfaithful, lazy, gold-digging, and always sexualized. Female characters are either “babes” or “bitches” in Johnny’s view, whereas Mark observes, “Oh man, I just can’t figure women out. Sometimes they’re just too smart. Sometimes they’re just flat-out stupid. Other times they’re just evil.” (Smart, stupid, evil—the three potential states of a woman, according to the Book of Mark.) Along with Wiseau’s rather slimy use of soft-core sex scenes that seem to carry on forever, there’s a debauched undercurrent to the film’s treatment of women, one made even pervier given the film’s pretense of a pseudo-wholesome and emotionally profound melodrama.

Of course, a cultish fandom has formed around Wiseau as well. Having supposedly bankrolled the $6 million production from a Korean leather jacket importing scheme, the independently wealthy filmmaker has maintained his mystique since the film’s release. At the same time, The Room and its release demonstrate the ego of a shameless self-promoter: To publicize his film, Wiseau purchased a billboard featuring his then-unknown face, arrived at the lackluster premiere in a limo, and submitted his flop for Oscar consideration. Meanwhile, his film presents Johnny as a sort of sexual icon—excellent in bed, emotionally supportive, great at tossing the football with friends, and this generation’s James Dean from Rebel Without a Cause (“You’re tearing me apart, Lisa!”)—even though he looks like a former stand-in for The Crow who later became a serial killer. With an ego this unchecked, who wouldn’t be oddly drawn to the resulting abomination?

To dwell on every bizarre detail of The Room would miss the point and rob you of the minor joy that is watching this film, preferably with a crowd, and definitely while under the influence of alcohol or narcotics. Midnight screenings of The Room appear every few weeks at my local Uptown Theater in Minneapolis, where Wiseau has made appearances to fan the fervor; chances are, the film plays somewhere near you as well. Attend one of these screenings for the full cult value, or simply gather a group of MST3K-loving friends for home screening. The Room and Wiseau have an undeniable appeal, like that of a car wreck or nineteenth-century freak show. The combination so ugly and terrible and weird, so artless and bungling, though it’s also sort of irresistible. But judging the film on any conventional scale proves impossible. Surely, the film has earned, and deserves, a zero-star rating. Still, there’s no denying the pleasure one receives from the viewing experience—not from the film, per se, but from the experience of watching the film. The Room doesn’t work on any level that it’s meant to, but it functions quite well on the level of cult-camp viewing. And given the rarity of a genuine self-unaware cult or camp experience—which many filmmakers try, and fail, to replicate, resulting in hollow poser efforts such as Repo! The Genetic Opera—a film as authentic and dreadful as The Room must be celebrated.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review