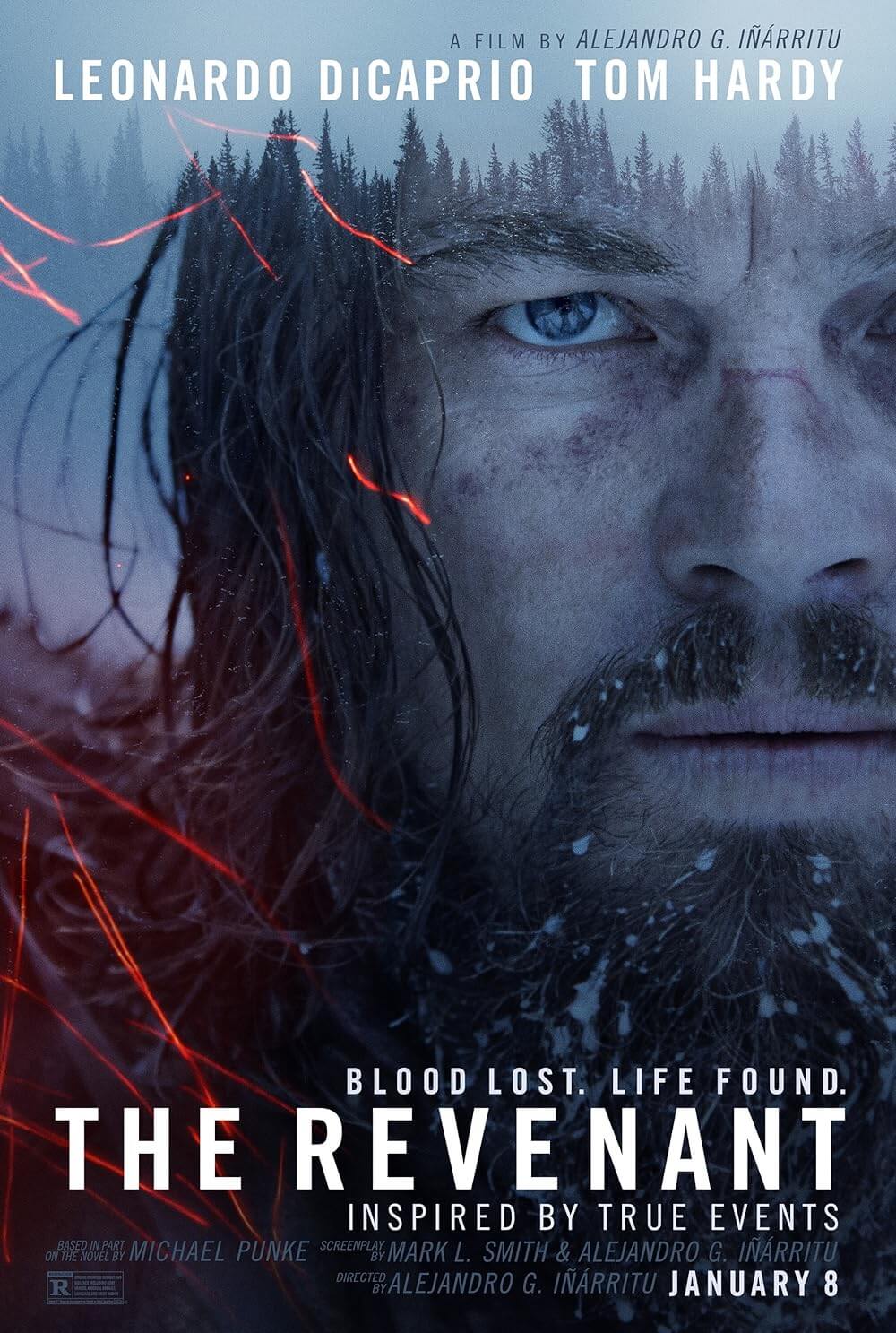

The Revenant

By Brian Eggert |

At once spiritual and primal, The Revenant stands as Alejandro González Iñárritu’s elegy to Nature in all its cruelty and beauty. Although the story contains familiar Old West elements about revenge and man’s survival in the unforgiving outdoors, there’s a visual and narrative poetry that elevates the picture to high cinematic art. This film showcases often breathtaking panoramas, shot with natural light and immersive depth of field by cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, and these images link the punishing experiences of the film’s protagonist with the beyond-words splendor of its setting. Iñárritu’s passion project features Leonardo DiCaprio in a tour de force performance as an early nineteenth-century explorer, but The Revenant also showcases the director’s uncompromising vision, both in terms of what appears on the screen and how it was achieved. Iñárritu demands much from his audience, asking us to endure a series of punishing physical trials depicted in equal measures of visual majesty and harsh realism. But those willing to face the confronting film head-on reap the rewards of one of 2015’s best films.

Iñárritu’s film has had a long road to the screen, from its development to the much-publicized shoot. The story is “based in part on” Michael Punke’s 2002 book The Revenant: A Novel of Revenge, which follows the true story of Hugh Glass, an American frontiersman and fur trapper. Glass famously survived a bear attack and, abandoned and left with no weapons or provisions by his fellow explorers, traveled from the Grand River in present-day South Dakota to Fort Kiowa on the Missouri River, some 200 miles away. From there, Glass set out to find the fellow trappers who left him for dead. Though he did not take revenge on his former associates and only recovered his stolen weapons, he earned the nickname “the revenant,” a French word meaning ghost or returner. Glass’ story was previously filmed in 1971 as Man in the Wilderness, distributed by Warner Bros. and starring Richard Harris. However, that film scarcely captures the unbelievable visceral extremes of Glass’ physical toil. The film rights for Punke’s book were purchased in 2001, before the original publication. Various talents have since been involved in developing an adaptation and then dropped out, including directors John Hillcoat and Park Chan-wook, and stars Samuel L. Jackson and Christian Bale.

Finally in 2011, Iñárritu agreed to direct with a budget of $60 million, financed by Twentieth Century Fox—reteaming with the director once more after their Fox Searchlight label distributed his Best Picture winner at 2015’s Oscar ceremony, Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance)—RatPac Entertainment, and Megan Ellison’s Annapurna Pictures, among others. Iñárritu wrote the script along with Mark L. Smith and diverted much from the source material. The film’s most notable alteration is avoiding factual reference to time and place, whereas the book featured maps and references to actual locations. Rather than detailing the specific setting and length of Glass’ punishing journey, we experience them through DiCaprio’s performance. There’s also no inner thoughts or voiceover from Glass; after the character’s throat is nearly clawed out by a grizzly bear, DiCaprio channels Glass’ anguish and desperation through grunts and the occasional, grumbled line of dialogue.

The film’s narrative follows the basic trajectory of Hugh Glass’ real-life experiences, while the character has been altered to enhance the more ethereal and spiritual elements of the story. Glass guides a company of fur trappers, commanded by Captain Andrew Henry (Domhnall Gleeson), through dangerous territory after securing their loot. Alongside his half-Pawnee son Hawk (Forrest Goodluck), whom Glass fathered with his late Pawnee wife. She was killed by an American officer, and Glass responded by killing the man—a legend that already precedes him when the film begins. After surviving an attack by a band of Arikara natives, Henry’s company loses a third of their party and looks for sanctuary in the forest, where they bury their furs until Glass can lead them through the wilderness to safety. There, Glass disrupts a mother grizzly with her two cubs, leading to an unforgettable, brutal attack in which the bear rips and bites at Glass’ back, swipes him down, and finally steps on his head before he’s able to kill the beast—though he’s left torn up beyond belief and near death. Achieved with stunningly realistic looking CGI, this scene will have you squirming in your seat and gasping aloud at its savagery.

Though they expect Glass to die, Henry leaves two men behind, Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy) and Bridger (Will Poulter), along with Hawk to ensure he receives a proper burial when the time comes. But the wicked Fitzgerald, impatient and scared, kills Hawk and convinces Bridger to leave Glass behind. They cover him in a thin layer of soil, burying him alive, and make their way over mountains to safety. Glass, meanwhile, wills himself along, impelled by fever dreams of his wife’s spirit and the need to avenge his son. Surviving on roots and an occasional mouthful of raw animal flesh, Glass heals slowly as he carries himself across impossible country and encounters more Arikaras, a lone and friendly Pawnee survivor, and a band of ruthless French trappers. Along with the brutality of the terrain, hunger, and hypothermia, these obstacles are mere interruptions until Glass can find Fitzgerald.

Principal photography began in October 2014 in Canada and was supposed to wrap in March 2015, but when the weather did not provide the needed snow, the production moved to Argentina. The shoot was described as “a living hell” by crewmembers because of the physical requirements of filming on location in sometimes sub-zero temperatures, but also because producer Jim Skotchdopole clashed with the director, who, after a six-week production hiatus beginning in December 2014, was replaced by producer Mary Parent. Iñárritu insisted on filming on real-life locations and shooting in chronological sequence—a rarity for most productions with a larger budget. What’s more, Iñárritu and Lubezki (who also shot Birdman) wanted to use natural light and shoot in extended, unbroken shots to engage the viewer in the film’s most harrowing moments. With the weather changing every day, it proved difficult to achieve similar light for a sequence that could not be completed in one day of shooting, which meant a strange balance of rehearsals and on-set improvisation was necessary.

Combined, all of these requirements represent a visually ambitious but practically daunting production. Iñárritu told The Hollywood Reporter, “If we ended up in greenscreen with coffee and everybody having a good time, everybody will be happy, but most likely the film would be a piece of shit.” To be sure, all of Iñárritu’s bold choices come to wonderful life on the screen, but at a heavy cost—the director’s methods required shooting until August 2015, with even more shooting after that, skyrocketing the budget to $95 million at first. Though, the final cost of the film was closer to $135 million, more than double the original price tag. But the director’s obsessive, demanding methods and overall meticulousness are meant to immerse his actors and audience in the story and dreamlike wonder the film has toward the natural surroundings.

Describing the sheer gorgeousness of The Revenant proves challenging. How can you put such exquisiteness into words? Every shot of Lubezki’s fluid, probing camerawork captures the grayish, luminescent light the production found in Calgary, Alberta, and Argentina—places that Iñárritu and Lubezki could pass off as virgin territory. The difficult conditions of the shoot seem to have challenged Lubezki to achieve several shots and sequences that feel too beautiful to be real. And yet they are. There’s also the virtuosity of Lubezki’s approach to consider: During one battle scene early on, we follow a trapper in the fray; he’s cut down by an Arikara on horse, who the camera now follows; the Arikara is shot by a trapper, and now the shot follows him. And so it goes, on like this from one combatant to another in a brilliant shot. In another scene, Lubezki gets so close to DiCaprio that his breath fogs up the lens. It might seem like an interesting accident that occurred and was left in as a flourish; however, Iñárritu uses breath in a significant transition from fog on the lens to clouds in the sky, and then to the breath of Fitzgerald far, far away. This kind of visual poetry is everywhere from epic battles to dream sequences in The Revenant.

Just as Lubezki’s lensing places us on a merciless landscape, Iñárritu draws the primeval out of his actors. With this role not offering much dialogue, DiCapio embodies a raw, elemental performance rooted in the purest kind of acting—reacting to one’s environment. He’s not unlike the very bear who attacked him, lashing out with unbridled rage at the one who threatened, or in this case killed, his young. As Glass’ dreams guide his character’s conscience, DiCaprio is able to communicate a pure, linear mission of revenge with a layer of complex internal dialogue behind his eyes, further shaped by the film’s dream sequences (and Ryuichi Sakamoto’s breathy score). At a crucial turn in the film, DiCaprio looks right into the camera so that we might fully acknowledge the suffering this man endured, and it’s a transporting moment. The supporting cast of Gleeson and Poulter are excellent as well, whereas Hardy is another force of nature altogether—a cruel man operating on much the same level of pure survival of Glass, except without an inkling of decency or regret.

The Revenant may seem narratively simple, but its treatment is a wonder. Call it Jerimiah Johnson meets The New World, as there is indeed a Terrence Malick-esque poetry to the work. Iñárritu even uses Malick’s frequent production designer Jack Fisk and costume designer Jacqueline West, who lend to the film’s all-encompassing sense of realism throughout. Shots of the Sun through the trees and the dreamy, poetic presentation feel less like a wilderness adventure story than a spiritual journey into the primal nature of human beings. That unruly throughline is balanced only by Glass’ later, rare, and very human ability to control those primal instincts. Few performers could achieve that interplay to the exceptional extreme that DiCaprio achieves here. From his use of visual to spiritual to formal bravado, Iñárritu has made a striking motion picture whose shared visual and thematic weight amount to a rare kind of cinematic grace.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review