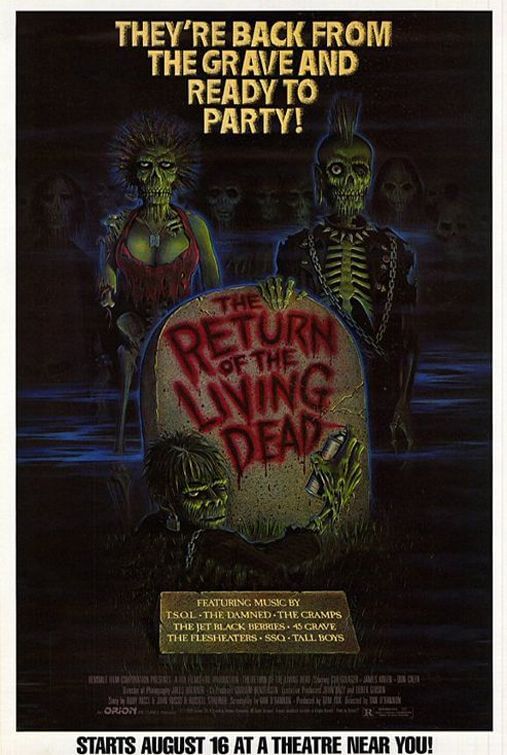

The Return of the Living Dead

By Brian Eggert |

Part spoof comedy, part kitschy horror, The Return of the Living Dead was tailor-made to achieve cult status. Had it been released today and not in 1985, audiences would see its inclusion of punk rockers, talking zombies, larger-than-life absurdist humor, and gooey special FX as an obvious commercial appeal to a niche market, and would thus reject it. But nostalgia maintains the movie’s enduring appear. Writer-director Dan O’Bannon works from a weird realm that mixes heavy metal with nudity and gore, but also macabre yet farcical humor born from 1980s schlock. It’s all loosely tied together with the thinnest possible plot, and if not for a fun balance of zombie horror and comedy, it might be difficult to overlook its complete lack of an ending or blatant exploitative quality. Nevertheless, the movie does not merely replicate George A. Romero’s standardized zombie-isms or attempt to conform. O’Bannon introduces new, decidedly post-modern ideas about zombies that came and went with this title and its immediate sequel from 1988, only to be returned to and celebrated decades later.

Following Romero’s Night of the Living Dead in 1968, co-writers Romero and John Russo collaborated once more (on the 1971 romantic comedy There’s Always Vanilla) and then never again. Years later in 1978, Russo published a little-read novel entitled Return of the Living Dead, a sequel to their original zombie film that established his legal ownership of the “Living Dead” label. That same year, Romero went on to make Dawn of the Dead, and later Day of the Dead (1985), to not always impressive box-office success. As Romero’s cult celebrity bloomed and zombie fans formed a subculture, his zombies became iconic for their slow movements and flesh eating. Meanwhile, Russo sought to produce an adaptation of his book. He and producer Tom Fox hired Poltergeist director Tobe Hooper to oversee the production, but Hooper chose to make Lifeforce instead. Oddly enough, O’Bannon, the writer of Alien (and also Lifeforce), was hired in place of Hooper and tossed aside Russo’s original text for an altogether unique approach.

O’Bannon’s vision employs tongue-in-cheek references to Night of the Living Dead but doesn’t use the same zombie rules as Romero. The Return of the Living Dead’s zombies aren’t mindless corpses shuffling along toward the next human meal, nor does a simple bullet to the brain render them un-reanimated. O’Bannon’s zombies might be considered the first running examples. And though they hardly sprint like those in Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later, they’re certainly better on their feet than Romero’s. They hurry along and leap from the trees at their prey with a specific meal in mind, so to speak: brains. Every zombie that has ever wailed “Brains!” in the subsequent decades has taken a cue from The Return of the Living Dead. As we learn from one of the movie’s talking zombies, eating the brains lessens the pain of death—a haunting and underutilized notion. Even scarier, O’Bannon’s zombies can’t be killed, no matter how much dismemberment they endure. And even if they’re burned, the noxious gas that caused their reanimated state seeps into the atmosphere and comes back down with the next rainfall.

I t all begins because of two bungling idiots at a medical supply warehouse. When Frank (James Karen) trains in young Freddy (Thom Matthews) for his first day on the job, he tells the new guy about the strange government drums that had been mistakenly delivered years ago after a zombie outbreak cleanup. As Frank explains, Night of the Living Dead was based on a real story, and the authorities merely asked Romero to change a few facts around—a detail in O’Bannon’s script that explains why Romero never attributes his zombie outbreak to any particular source. Turns out, the government inadvertently created zombies. Of course, Frank and Freddy cause one of the containers to ooze green gas (never good), reanimating every dead specimen in the warehouse (a medical cadaver, bisected dogs, pinned butterflies, etc.). They also release a liquefying corpse and infect themselves in the process.

t all begins because of two bungling idiots at a medical supply warehouse. When Frank (James Karen) trains in young Freddy (Thom Matthews) for his first day on the job, he tells the new guy about the strange government drums that had been mistakenly delivered years ago after a zombie outbreak cleanup. As Frank explains, Night of the Living Dead was based on a real story, and the authorities merely asked Romero to change a few facts around—a detail in O’Bannon’s script that explains why Romero never attributes his zombie outbreak to any particular source. Turns out, the government inadvertently created zombies. Of course, Frank and Freddy cause one of the containers to ooze green gas (never good), reanimating every dead specimen in the warehouse (a medical cadaver, bisected dogs, pinned butterflies, etc.). They also release a liquefying corpse and infect themselves in the process.

Frank calls Burt (Clu Gulager), the warehouse manager who shows up and, just like Frank and Freddie, doesn’t have the good sense to call the “in case of emergency” number stenciled on the government drums. Instead, Burt does the least logical thing possible: he tries to cover up the evidence by cutting a zombie up into pieces and convincing his friend, Ernie (Don Calfa), a mortician with crematorium facilities in the cemetery across the street, to burn the twitching remains. Once Ernie sets them ablaze, more green gas drifts from the smokestacks into the clouds and then, with the rain, back down into the cemetery soil, reviving hundreds of buried dead into brain-eaters. Meanwhile, the story also follows a group of random punks whose sole purpose within the movie is to increase the body count. As they wait for their friend Freddy to finish his shift, they bide their time in the cemetery—until zombies begin to emerge and eat members of their gang, that is.

Despite some infrequent, underwhelming moments, the practical makeup remains the movie’s showcase. Some of the zombies, such as the liquefied “Tarman” locked in the medical supply warehouse basement, look superb and disgusting. Also impressive is a female torso-only cadaver conceived with animatronics; her cries for brains are both funny and creepy. Indeed, these zombies can think, talk, and even problem-solve. Among the funniest gags in The Return of the Living Dead is one that involves a series of paramedics and policemen who are quickly consumed by zombies. In each case, a zombie gets on the radio afterward and says, “Send more cops” and eventually “Send more brains”—a demand to which emergency services dutifully comply. Elsewhere, it seems like O’Bannon’s makeup crew just rubbed mud on their extras, resulting in zombies who hardly look as though they’ve been rotting in the ground for years.

However, alongside the occasional squirm-inducing gore and laugh-out-loud moments of silliness, there are less savory scenes. Consider the female punk named Trash, played by scream queen Linnea Quigley. At one point early on, this sexed-up, red-wigged rebel talks herself into a tizzy. Obsessed with death and presumably sadomasochism, she rubs her thighs and seductively says her greatest fear is being devoured by old men. Then she begins disrobing in the cemetery. “Somebody get some light over here,” one of her fellow punks calls out. “Trash is taking off her clothes again.” They all gather around a tomb, atop of which Trash proceeds to dance naked in the light of the gang’s road flares. As things go south on the zombie front, Trash never regains her clothes; she remains mostly naked, even after she’s conveniently devoured by a group of “old men” zombies and turned into a gray-skinned, brain-eating monster herself. Quigley’s thankless role injects the requisite sex element into this 1980s horror fare, but her presence feels cheap and uncomfortable today.

However, alongside the occasional squirm-inducing gore and laugh-out-loud moments of silliness, there are less savory scenes. Consider the female punk named Trash, played by scream queen Linnea Quigley. At one point early on, this sexed-up, red-wigged rebel talks herself into a tizzy. Obsessed with death and presumably sadomasochism, she rubs her thighs and seductively says her greatest fear is being devoured by old men. Then she begins disrobing in the cemetery. “Somebody get some light over here,” one of her fellow punks calls out. “Trash is taking off her clothes again.” They all gather around a tomb, atop of which Trash proceeds to dance naked in the light of the gang’s road flares. As things go south on the zombie front, Trash never regains her clothes; she remains mostly naked, even after she’s conveniently devoured by a group of “old men” zombies and turned into a gray-skinned, brain-eating monster herself. Quigley’s thankless role injects the requisite sex element into this 1980s horror fare, but her presence feels cheap and uncomfortable today.

Even less impressive is the ending, which concludes with The Bomb blowing this small town to smithereens. Rather than shoot a new scene, O’Bannon replays some of the exact same footage from earlier. As contaminated rainwater drains into the cemetery, causing another zombie outbreak, and the same skeletal body emerges from the ground to the same heavy metal riff. It’s a lazy moment that cannot help but leave the viewer with a bad taste. Likewise, most of the acting crosses into pure camp. Karen and Matthews, who returned in similar roles for the sequel, alternate between grating and utterly hilarious, as their characters gradually sicken from gas poisoning and transform into zombies. Though their over-the-top hysterics seem comically outlandish at first, O’Bannon leaves them in this whining state for far too long, which of course becomes funny again. But after a few minutes of listening to them scream and howl, we wish they’d just shut up and die already.

In his original review, Roger Ebert called the movie a “sensation machine,” and perhaps he’s right. It’s impossible to watch The Return of the Living Dead without reactions of disgust, annoyance, hilarity, and occasionally terror. That O’Bannon’s zombies cannot be killed with a bullet to the brain remains an intriguing, thoughtful, and scary notion. But O’Bannon is more interested in the potential laughs than scares. And so, the writer-director delivers some hilariously campy moments and details, such as Ernie’s curious affection for all things German (undoubtedly a Nazi reference, given his access to a furnace). Made in the spirit of intentional bad taste, O’Bannon achieves that and more—to such an extent that The Return of the Living Dead doesn’t work unless you’re surrounded by a bunch of rowdy horror fans with a broad sense of humor and no concern for story.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review