The Return

By David Hill |

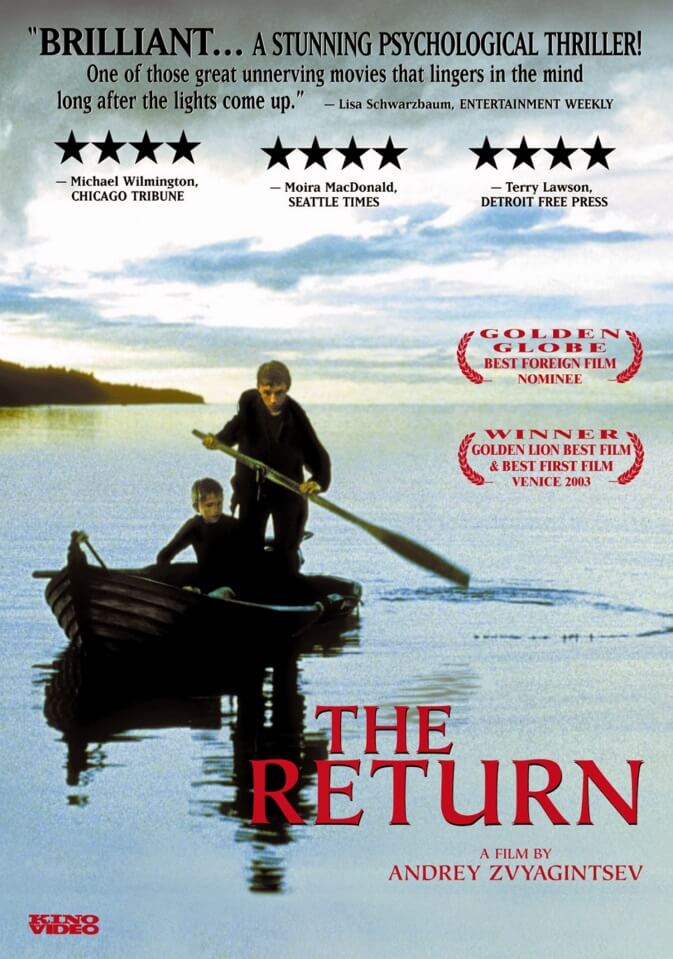

In 2003, Russian director Andrey Zvyagintsev came seemingly out of nowhere to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival for his visually stunning debut feature The Return. This award announced Zvyagintsev as a major directing talent, and he went on to become one of the most important and respected contemporary directors in Russian and international cinema. However, his triumph at Venice was overshadowed by the fact that child actor Vladimir Garin, who played a starring role in The Return, tragically passed away shortly after the filming was completed. In his award acceptance speech, a visibly moved Zvyagintsev dedicated the Golden Lion to Garin in what was a bittersweet moment for the director.

The Return tells the story of two young teenage brothers, Andrey (Garin) and Ivan (Ivan Dobronravov), who go on a trip with their long-absent father (Konstantin Lavronenko). It opens with a spectacular sequence involving the two brothers and four of their friends. All six boys are supposed to jump into the water from a high tower as a dare. Ivan, who suffers from fear of heights, is the only one who does not dare to jump, and the others call him a chicken and abandon him. He is only able to descend from the tower once his mother (Nataliya Vdovina), who is shown as a loving and protective parent, comes to his aid much later.

On the next day, when Andrey and Ivan return home after having had a fight, they are stunned to learn from their mother that their father has returned home from a twelve-year absence. Zvyagintsev quickly establishes the father as an authoritarian patriarch and as a direct opposite to the mother, among other things by shooting the father from a slightly lower angle than the rest of the family members during a tense dinner scene where the brothers meet their father for the first time after his return. Following this reunion, the father takes the two brothers on a trip that ends up being very different from what they had imagined.

As it turns out, the opening sequence involving the tower does not remain the only test of courage that Andrey and Ivan are subjected to in the course of The Return. Their father puts them through various horrendous ordeals during their trip, which takes on an almost mythical dimension as the three characters leave civilization more and more behind and end up on an uninhabited island in the Russian wilderness. On that island, there is another crucial scene involving a tower. This scene once again underlines the film’s oppositional portrayal of the warm and loving mother on the one hand and the cold and authoritarian father on the other hand, and it makes for a fascinating bookend to the film’s opening sequence.

The screenplay of The Return was written by Vladimir Moiseyenko and Aleksandr Novototsky, and it was revised by Zvyagintsev (although uncredited). It is deliberately ambiguous and leaves much to the viewer’s interpretation. In particular, the nature of the father’s twelve-year absence and the motivation for his actions are never explained, and there is a mysterious strongbox that the father digs up on the uninhabited island whose contents are never revealed. This ambiguity is one of the reasons why The Return does not unfold its full impact until after the credits have rolled. It is a film that lingers on the mind and that can be read in a number of different ways, namely theologically (with the father representing a figure of God), psychologically (with the film being a meditation on masculinity and power), and politically (with the father representing the authority of the Russian state). Zvyagintsev has refused to comment on the actual meaning behind The Return, stating that he respects the audience’s intelligence and own creative potential.

The screenplay of The Return was written by Vladimir Moiseyenko and Aleksandr Novototsky, and it was revised by Zvyagintsev (although uncredited). It is deliberately ambiguous and leaves much to the viewer’s interpretation. In particular, the nature of the father’s twelve-year absence and the motivation for his actions are never explained, and there is a mysterious strongbox that the father digs up on the uninhabited island whose contents are never revealed. This ambiguity is one of the reasons why The Return does not unfold its full impact until after the credits have rolled. It is a film that lingers on the mind and that can be read in a number of different ways, namely theologically (with the father representing a figure of God), psychologically (with the film being a meditation on masculinity and power), and politically (with the father representing the authority of the Russian state). Zvyagintsev has refused to comment on the actual meaning behind The Return, stating that he respects the audience’s intelligence and own creative potential.

Regardless of how one chooses to interpret The Return, there can be no doubt that it is an accomplished film. With the help of his cinematographer Mikhail Krichman, Zvyagintsev has come up with some stunning shots of the Russian wilderness. His direction is remarkably assured, especially for a debut feature film. He adopts a deliberate pace, and he takes his time to build a tense atmosphere of mystery and impending doom. The film’s color palette is muted, and it is mostly made up of blues and greys. However, the father’s red car constitutes a notable exception that underlines the father’s alienation from the other family members.

Furthermore, The Return features great performances across the board, especially by the two child actors, Garin and Dobronravov. As already mentioned, Garin tragically passed away shortly after the filming of The Return was completed. The circumstances of his death chillingly mirror the film’s opening sequence: After having been dared by friends to jump into a lake from a high tower not far from where the opening sequence of The Return was shot, Garin drowned after he had presumably gotten a cramp because of the freezing water.

Despite the tragedy of Garin’s death and the fact that The Return can be read as a sly critique of Russia, Zvyagintsev’s triumph at Venice was celebrated in his home country. It was widely reported upon in the Russian media, and Vladimir Putin even congratulated Zvyagintsev on his win. This stands in contrast to the controversial reactions that some of the director’s more recent films have received in his homeland, in particular his 2014 film Leviathan, which was criticized by Russia’s Minister of Culture at the time. Meanwhile, Western critics heralded The Return as a return to the world stage for Russian cinema, and they drew comparisons between Zvyagintsev and the great Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky (Solaris).

The Return is a well-crafted film that contains some stunning images and great performances. The film can be enjoyed on a pure surface level given its emotional power, but it also leaves room for various subtextual readings. While its deliberate pace and ambiguity will undoubtedly frustrate some viewers, patient viewers who are willing to engage themselves with the film will find watching The Return a deeply rewarding experience.

Bibliography:

Menashe, Louis. “The Return.” Cinéaste, Vol. 29, No. 2, Spring 2004, pp. 25-27.

Kroll, Thomas. “Die Rückkehr.” Pädagogisches Begleitmaterial. EBJW and Vision Kino, 2006, https://www.kinofenster.de/download/the_return_die_rueckkehr_filmheft_pdf. Accessed 12 October 2020.

Walsh, Nick Paton. “‘He is alive in my head.'” The Guardian. 11 September 2003, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2003/sep/12/venicefilmfestival2003. Accessed 12 October 2020.

David Hill is a lawyer from Switzerland who currently works as a legal counsel for an insurance company. He has long had a passion for cinema, and he uses most of his spare time to watch and research films. His main interest focuses on arthouse films, and he occasionally makes contributions to Deep Focus Review as a guest writer.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review