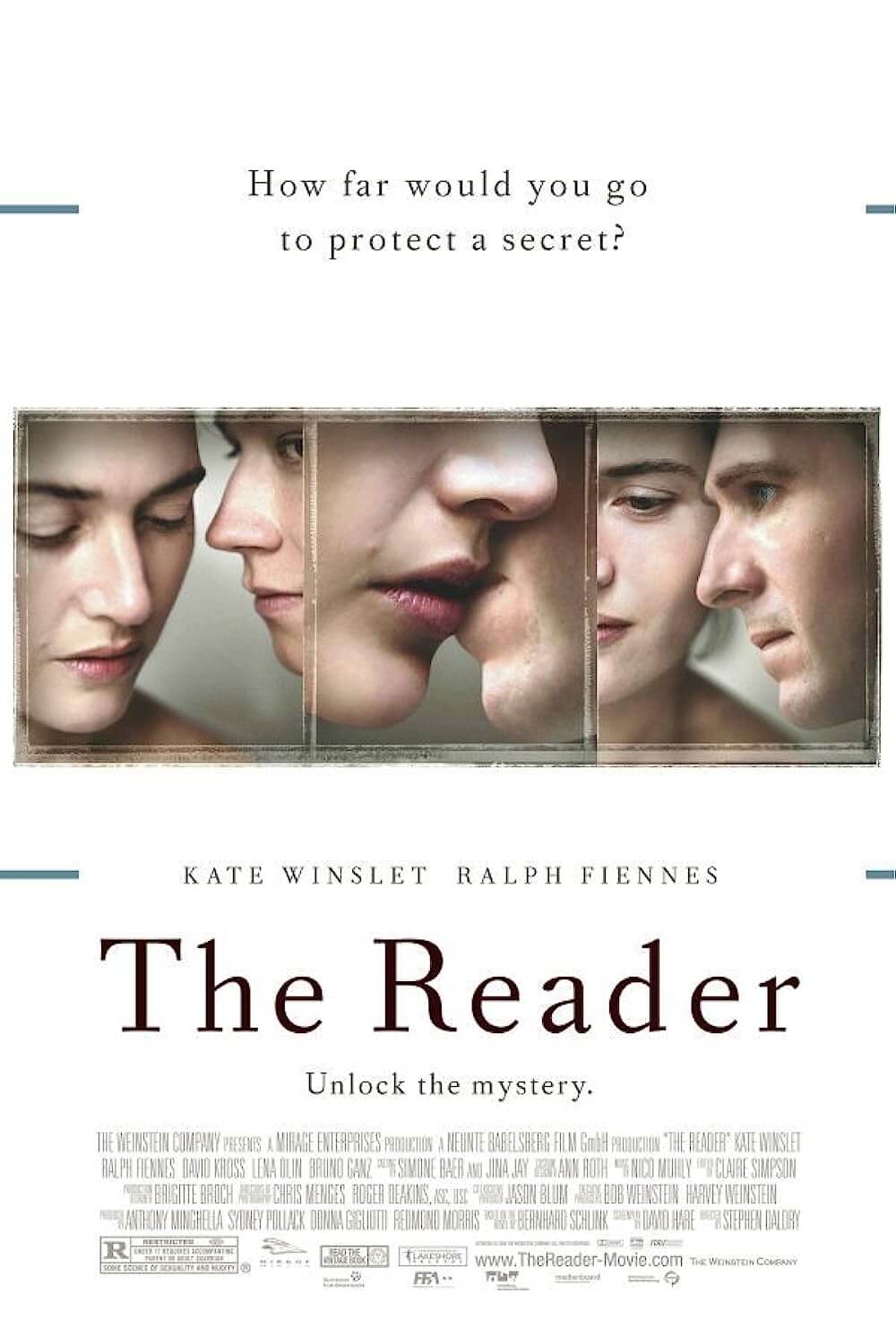

The Reader

By Brian Eggert |

Asking bold and unanswerable questions about morality and the limits of forgiveness, The Reader presents a Nazi character in three-dimensional terms, refuses to damn its subject outright, and instead considers the entire picture. And not just the horrifying sections therein. Screenwriter David Hare adapts the heavily circulated novel by Bernhard Schlink, retaining its probing themes of conscientious ignorance and the eventual acceptance of responsibility with surprising sensitivity.

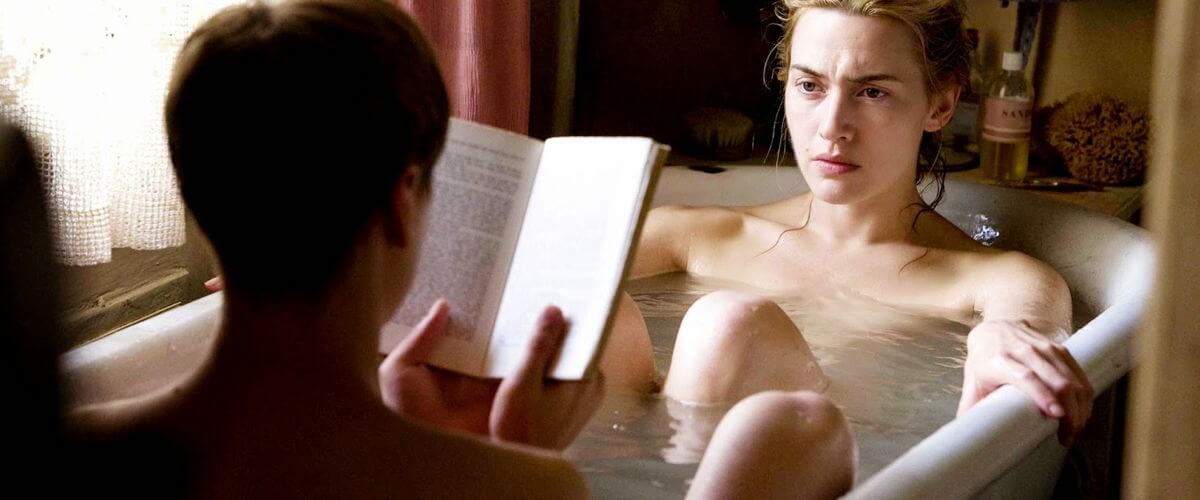

The story begins in Berlin around 1958, wholly engulfed in WWII’s shadow. Teenager Michael Berg (David Kross) finds himself sick on the way home from school; he’s rescued by Hanna Schmitz (Kate Winslet), a woman in her thirties who escorts him home. When finally cured after months with Scarlet Fever, he looks her up to thank her, and the two engage in a sudden affair. Director of Billy Elliot and The Hours, Stephen Daldry constructs honest bedroom scenes that are curiously frank and, like a Rembrandt painting, avoid sexual exploitation to reside in natural and psychological nakedness. Hanna asks that she be read to as their pre-coital ritual, and Michael proceeds, doing everything she asks, always on her terms. But eventually she realizes their affair has held him back from a normal teen life, and she disappears.

Years later, Michael attends a law school seminar under a Socratic professor (Bruno Ganz), who takes his students to witness an ethically perplexing case that will shed light on the course’s theme of morality vs. law. In court, Michael watches as Hanna is placed on trial, much to his shock and revulsion, for her time as an SS Guard at Auschwitz, where she and nine other guards decided who was sent for execution and who lived. Hanna bears a childlike confusion at the trial, responding to the questions with a blind honesty and orderly sensibility. She’s specifically accused of allowing three hundred Jewish victims to burn to death in a church fire; the doors were locked, and if she and the other guards opened the doors to save them, the prisoners would’ve escaped. As a guard, it was her duty to keep order, thus she couldn’t open the doors. Emotion never entered into it—and certainly no inner dialogue about right and wrong.

Drafting Hanna as a human character versus an inhuman Nazi comes at a great price for the film, which is unlike any cinematic exploration of the Holocaust in that it views the events in gray terms. Of course, how can we blindly empathize with a Nazi who failed to prevent the deaths of three-hundred people based on some deranged sense of duty? Then again, what about the rest of her life? Through Michael’s eyes, his version of Hanna is the lover from his memories of adolescence. Her Nazi side is unreal, something he hasn’t experienced or witnessed, therefore he can forget about that aspect of her life and remember her fondly. Hanna plainly says she lives in the moment and resists brooding on the past (not that this is any consolation or redemptive argument for her judgment). Indeed, the film weighs how the postwar generation of Germans live with the darkness of their past, and uses the key of reading, rather illiteracy, as a clear metaphor for how much of the country systematically played ignorant to the Hitler-purveyed atrocities around them.

The film’s structure is told in long flashbacks remembered by an older, emotionally distant Michael, played by Ralph Fiennes. The broken timeline jumps back and forth, flashbacks within flashbacks, which is more distracting than dramatically effective. Shown in the decades following, he remembers Hanna at lonely or ponderous times, sometimes affectionately, but never dismisses or grants her forgiveness for her role during the war. The Reader doesn’t excuse Hanna’s actions, leaving her judgment, however uncertain, up to the viewer. How you feel about Hanna is something you’ll debate with yourself long after the end credits.

Some critics have argued the film invalidates itself when in one of the last scenes Michael visits Ilana Mather, the daughter of the church fire’s sole survivor. Played by Lena Olin, Ilana tells Michael, who in pseudo-confessional has come to explain his relationship with Hanna, “Go to the theater if you want catharsis.” In effect, because it tells a story that treats a Nazi with humanist consideration and spends comparatively little time mourning for the Jewish dead, Ilana waves off films of this sort as unrealistic. And no doubt she would condemn this film specifically for lamenting the death of Hanna. But the story poses big questions to its audience, unlike this year’s very cut-and-dry The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, by asking you to consider individuals over events.

The production recalls The English Patient or The Talented Mr. Ripley in its sensitive yet profoundly complex tone, which makes sense, because the director of those films, the late Anthony Minghella, co-produced this picture along with the late Sydney Pollack (Out of Africa). Both Minghella and Pollack, to whom this film is dedicated, specialized in romances of an epic scale; both engaged complicated and often unsympathetic characters with an open mind, and both earned due attention from Mr. Oscar. No doubt Daldry’s film will be acknowledged by Academy voters as one of this year’s best, though the film’s impact rests chiefly on the shoulders of Kate Winslet, whose performance embodies the complex feelings held by the audience.

Winslet’s presence onscreen is simply haunting, leaving the viewer unsure how to feel about her Hanna Schmitz. She displays an omnipresent obsession for control and order, yet underneath resides an evident desire to escape. Exhibiting hints of nuanced complexity and inner disorder amid an exterior of straightforward mechanical regulation, Winslet does what only Claude Rains in Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious has done before: she creates a Nazi character who, though contemptibly involved in a monstrous faction, still shows evidence of compassionate humanity. Her performance offers some of the finest acting this year; perhaps she’ll finally earn that Oscar that’s eluded her so many times in the past.

The Reader will challenge your humanist views, if they exist, by presenting a moral dilemma under the gravest of circumstances. Whereas the Holocaust has become an easy go-to historical epoch for dramatic storytelling, this story changes convention and curiously offers ignorance as another piece of a puzzle—not as an excuse to the Hannas out there, but as a chief symptom of an atrocity we’re still desperately trying to understand. Our emotional reactions surprise us, especially our empathy for the curious relationship that ensues, despite its clearly disturbing undertones. And although the film offers no solution to the pained questions of culpability and intention, its haunting effect is undeniable and will leave you pondering for days to come.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review