The Purge: Election Year

By Brian Eggert |

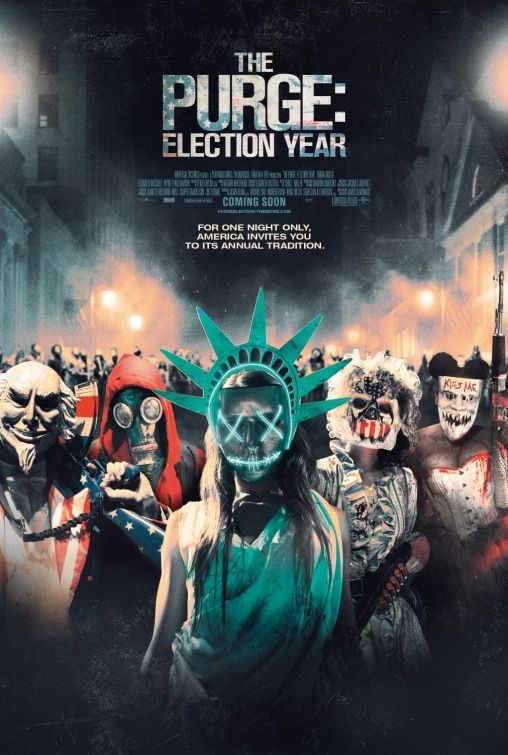

David Bowie’s “I’m Afraid of Americans” plays over The Purge: Election Year’s end credits. This might represent the one redeemable quality about the third and most aggressive entry in writer-director James DeMonaco’s ongoing series for Blumhouse Pictures. Painting America as a den of bloodthirsty psycho-killers, the Purge idea itself seems ever more possible as the U.S. begins to look less like a democracy founded on equality and more like an isolationist idiocracy. After all, Donald Trump, star of Home Alone 2: Lost in New York, has a real shot at becoming president this year on a campaign of hatred. But instead of providing a precise critique, DeMonaco caters to his target audience by communicating in terms they can understand. The outcome contains all the subtlety of a gunshot to the face.

If you’re unfamiliar, the movies revolve around the so-called “Annual Purge,” 12 hours held each year on March 22, during which people may engage in all manner of crimes without legal repercussions. Designed by a bonkers political party known as the “New Founding Fathers of America” (or NFFA), the Purge was meant to cleanse people of negative emotions. As such, the Purge is the ultimate emotional laxative. At the same time, those who cannot afford to protect themselves from stalking nutjobs on Purge night become victims. And because those victims are often homeless, helpless, or minorities, many believe the NFFA has engineered the countrywide event as a way to rid the country of undesirables, as well as provide a source of revenue. As a result, the government saves on welfare by eliminating the homeless and poor; the insurance companies profit by increasing their “Purge coverage” premiums.

Rather than use this subtext to address any real-world political parallels, each Purge movie stands as a tense survival story, where a small group of people tries to stay alive until the Purge ends. Election Year and its predecessors remind me of Roger Corman’s exploitation fare from the 1960s and 1970s—Gas-s-s-s (1970) and Death Race 2,000 (1975) come to mind. Ultimately, they’re trash, pure and simple, with a smidgen of social commentary added to appear more intelligent than they really are. And while I suspect certain systems of government have been warped to keep the populace in check, DeMonaco is less interested in creating genuine relevance than tapping into his audience’s anger and providing an ugly form of catharsis. The effect is nothing more than cinematic rabble-rousing.

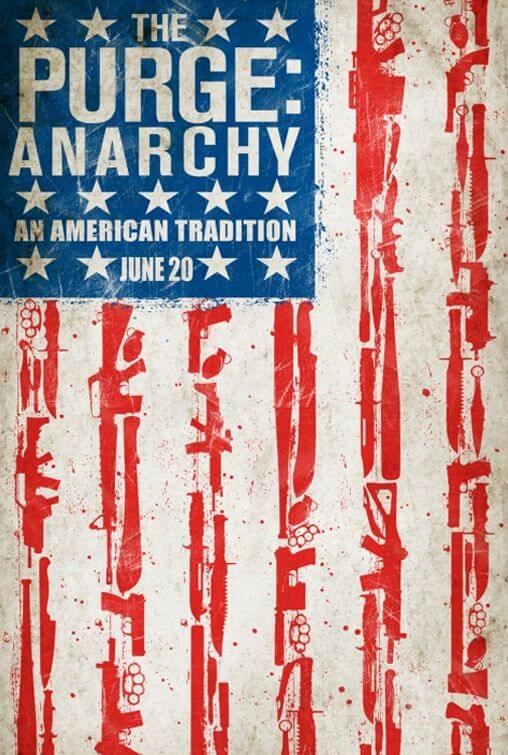

The Purge itself becomes a topic of political debate within Election Year, as the title suggests. Senator Charlie Roan (Elizabeth Mitchell, likable), who, as shown in the movie’s prologue, experienced some Purge unpleasantness sixteen years earlier, vows to do away with the carnal ceremony if elected POTUS. Her opponent, Minister Edwidge Owens (Kyle Secor)—a fascist NFFA stooge, prone to shouting “Purge and purify!”—arranges for Charlie to be assassinated on Purge night to ensure his victory. Charlie’s security detail is none other than Leo (Frank Grillo), the only returning character from The Purge: Anarchy. When Charlie’s other security forces prove ineffectual against the high-tech, white-power mercenaries on the NFFA’s bankroll, Leo must escort Charlie through chaotic city streets to keep her alive.

Along the way, they meet up with an underground movement determined to get Charlie elected and stop the Purge. A deli owner named Joe (Mykelti Williamson), his employee Marcos (Joseph Julian Soria), and their friend, a badass triage nurse Laney (Betty Gabriel), agree to protect Charlie as well. Also, the film dedicates lot of screentime to a couple of nasty teenage girls (Brittany Mirabile, Juani Feliz) determined to murder Joe and burn down his deli, all in pursuit of a candy bar. Throughout the night, Joe presents himself as the comic relief of the bunch, doling out racist remarks meant to be incorrigible; but he’s an offensive, lowest-common-denominator character. The audience in my screening loved him. Moreover, DeMonaco saddles his entire cast with the latest in mindlessly bad dialogue: “You got this?” Joe asks Leo. “I got this,” Leo responds. (If ever there was an overused phrase in movies today, it’s “I got this.”)

Within DeMonaco’s interesting, albeit logic-defying concept, Election Year puts forth a few inspired ideas and innovations within the Purge world. For example, we learn about “murder tourists” traveling to the U.S. from other countries to take advantage of Purge night. They get the jump on Leo and Charlie mid-film, each of them donning a different mask of a former president. Elsewhere, we see rival gangs formed in a circle around two opponents, who attack each other with swords and axes (this made me wonder if LARPers put away their foam weaponry, stop pretending, and engage each other with real weapons on Purge night). In future sequels (which will undoubtedly happen given the production’s meager $10 million budget), it would be fascinating to hear what other countries in DeMonaco’s world think of the Purge.

Not that the average moviegoer thinks about such things during Election Year. If they’re anything like the audience in my screening, they’re cheering, laughing, and shouting at the screen—oblivious or just unconcerned about the implications of both the movie and how they’re cheering it along. Again, Corman’s B-movies come to mind. However, unlike most exploitative releases from those days, Election Year is relatively well put together, thanks to clear nighttime lensing by Jacques Jouffret and only moderately hectic editing by Todd E. Miller. Worse, the Purge movies aren’t a cult phenomenon; they’re mainstream and bound to perform well, especially on a gimmicky July 4th weekend. The mean-spirited movie might even be admirable, in a grim sort of way, if it didn’t so irresponsibly reflect today’s increasingly vile populace. Ultimately, DeMonaco’s movie provides his audience with the very thing the movie seems to condemn: mindless, uninhibited aggression. And people seem to love it. Like the late David Bowie, that makes me afraid of Americans.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review