Reader's Choice

The Prestige

By Brian Eggert |

Christopher Nolan’s The Prestige involves the secret world of magicians who obsess over and make profound sacrifices for their craft. They thrive on new ways to make the ordinary do something unexpected, and then, to the audience’s delight and wonderment, reveal their mastery over the illusion. In many ways, that’s just what Nolan does in this tale of dueling magicians at the turn of the last century. Along with his brother Jonathan Nolan, the director adapts the 1995 novel by Christopher Priest and applies the three-part structure of a magic trick defined in the story: the Pledge shows the characters and their motivations; the Turn shows them doing extraordinary, impossible things; the Prestige reveals the nature of their illusions. Yet, there’s another type of magic in the film—the same kind of magic Arthur C. Clarke wrote about in his 1962 book Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry into the Limits of the Possible, when he claimed, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” And while the illusions and science—and the science of illusions—remain central to the narrative and its complex structure, what’s at stake, even more than his characters’ fates, is whether Nolan is as accomplished a cinematic magician. His challenge to the audience—“Are you watching closely?”—rewards upon first viewing, but, as with any magic trick, once you know how it’s done, the fascination dissolves.

This review is not so much a response to an initial screening—which, after seeing The Prestige in the theater in 2006, was enthusiastic—but a reaction to subsequent viewings (spoilers to follow). After seeing how the story plays out, how well does the film work? Does it have the same impact, despite the viewer knowing where it ends up? Many of the greatest films continue to grow and improve upon revisiting them, revealing hidden layers and dimensions. It’s a key aspect of what makes a classic. Others rely so much on a sense of gamesmanship that a second viewing will never be as satisfying as the first, so they’re best left to the fond memory of the initial experience. Certain facets of Nolan’s film, his first after directing the blockbuster hit Batman Begins (2005), have been enriched by time and reward closer inspection. Specifically, Nolan’s approach to form—how he creates a novelistic narrative structure and editing technique. However, the emotional payoffs and plot twists become less powerful upon revisitation, after the viewer has been exposed to its secrets, leaving the film to become a site of extraordinary details, most of which service the structure more than the drama.

Chronologically, The Prestige begins with two magicians, Robert Angier and Alfred Borden, played by Hugh Jackman and Christian Bale, respectively. They both work under Cutter (Michael Caine), who designs their illusions. Angier’s talent resides in the performance, in presentation, but at first, he sacrifices nothing for his craft. Borden does, however, and he believes that a great show is less about showmanship and more about the veracity of the illusion; great magic takes dedication. Borden believes a magician with a great trick cannot perform without first surrendering himself to the act. After Angier’s wife (Piper Perabo) dies onstage during an underwater escape routine, he blames Borden for tying the wrong knot and seeks revenge. Angier retaliates out of grief, and the two launch independent acts and stage personas before engaging in a years-long rivalry, each trying to out-magic and expose the other’s methods to the public. Though Angier is the more successful of the two financially, as an artist and craftsman, Borden proves superior. Angier’s desperation to outshine and thereby destroy Borden consumes him. Each man attends the other performer’s shows, and each man sabotages his opponent’s routine by posing as an audience volunteer, all while attempting to perfect a new trick.

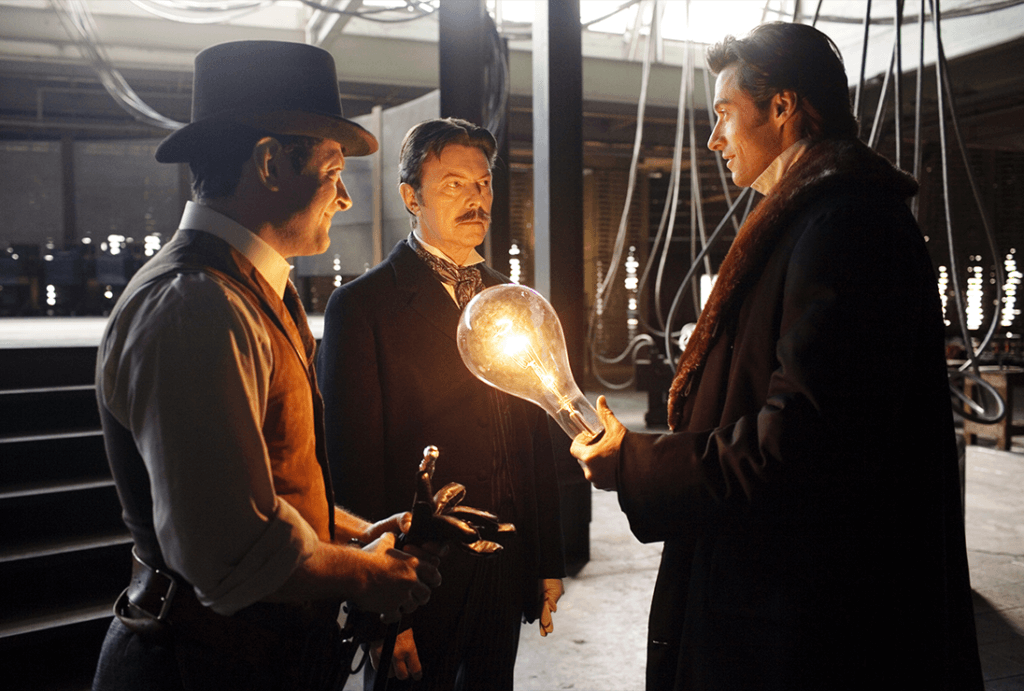

While the craft of magicians remains central to The Prestige—supported by legendary illusionist, technical advisor, and brief on-screen performer Ricky Jay—much of what makes the film unique is how the Nolans and editor Lee Smith structure the story. Priest’s book framed the past through Adam Westley, a contemporary publisher, who reads various documents and investigates the past with differing perspectives and viewpoints on the magicians’ rivalry. The film offers what has become a typically intricate structure for Nolan, who resists linear storytelling here in favor of a narrative arranged in the manner of a trick, armed with a reveal that doesn’t necessarily occur at the chronological finale. As scholar David Bordwell notes in his book Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages, the film enters from the middle and unfolds across several distinct timelines: the then-present, where Cutter teaches Jess (Samantha Mahurin), Borden’s young daughter, a disappearing bird trick; the recent past, involving Borden on trial for murdering Angier; the backstory of Angier and Borden first starting out with Cutter, leading to the fissure in their collaboration and start of their competition; and Angier’s trip to Colorado to visit Nikola Tesla (David Bowie) in hopes of acquiring an illusion to outdo Borden’s new gimmick, “The Teleported Man.” But Tesla does not devise mechanisms that appear magical; he discovers a kind of magic by harnessing the subline power of Nature through science. Nearly every piece of stage magic in the film is explained to us, but there’s no explaining Tesla.

Nolan often constructs his films in nonlinear terms to draw attention to timelines and structure, therein placing dramatic emphasis where a temporally straightforward presentation might not. The Prestige not only deconstructs the events around Angier and Borden and reorders them into a kind of puzzle, but it also places the narrative within two separate frames. In excerpts from Angier’s diary, he reads Borden’s encrypted notebook, thereby housing the narrative in a frame-within-a-frame, which the screenplay then segments in a nonlinear format. Such dramatic puzzlework has been relatively commonplace in Hollywood cinema since Quentin Tarantino popularized the trend with 1994’s Pulp Fiction, which reframed its narrative in nonlinear chapters. Although the structure sounds confusing, the real feat of The Prestige is that Nolan trusts the audience to piece together the timeline along the way, consciously and unconsciously assembling the crosscut pieces of the narrative. These threads burst onto the screen in the first few minutes, recalling the technique deployed later to disorienting effect on Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023). But where Oppenheimer’s structure rewards and matures on subsequent viewings, after the viewer has gone through the work of assembling the narrative in their mind, The Prestige reveals that the characters have fewer dimensions than one might hope. The film’s pleasure derives from the story and characters, but more from the pleasure one experiences from putting the pieces together.

Much of the drama involves secrets. How does Borden perform “The Teleported Man”? He stands on stage right, in front of the door of a boxed-in enclosure, and bounces a rubber ball toward an identical enclosure on the opposite side of the stage. He steps back into the enclosure, shuts the door, and suddenly opens the door stage left, just in time to catch the ball. Cutter, who works alongside Angier, attempts to convince him that Borden is using a double to accomplish the illusion. But that’s too simple for Borden, Angier believes, and he commits himself to discovering Borden’s secret. Angier even employs a double, Gerald Root (also Jackman), a comical and duplicitous drunkard, to replicate the trick. What’s revealed later is that Borden has committed his life to his craft—or rather, Borden and his identical twin alternate playing the role of his right-hand named Fallon, each split between the two personas. They have gone to extreme lengths to conceal that a twin exists, from cutting off fingers to ensure they look the same to keeping his wife Sarah (Rebecca Hall) and child Jess in the dark, regardless of how much it strains their marriage. For Borden’s trick, there is no magic, only what he conceals from the world. What’s disturbing is how much he eventually sacrifices to preserve his secret: Sarah’s emotional wellbeing and life, his twin’s freedom, and his daughter’s livelihood.

But just as “The Teleported Man” is about doubles, The Prestige draws thematic parallels between Borden and Angier, each of whom have their on-stage doubles while also reflecting one another. Nolan reinforces this throughout with cinematographer Wally Pfister framing Borden and Angier in identical shots in various scenes, suggesting that the two magicians have parallel obsessions, similar drives, and will meet the same ruinous end. For Angier, he seeks Telsa’s help to replicate Borden’s trick, and Tesla builds him a mysterious machine that, from the audience’s perspective, seems to actually teleport him. Angier learns that the machine doesn’t teleport; it copies. Regardless, he takes the machine to the stage, knowing that its use in his version of Borden’s trick will be unrepeatable because there is only one machine. And so, he takes Borden’s philosophy to “live the act” to a deathly extreme, resolving to kill a version of himself each night—self-destruction, both literal and symbolic, on an unthinkable scale—all in service of a stage performance to outmaneuver Borden. Like Dr. Frankenstein, Angier becomes an engrossed madman who wields an uncontrollable scientific force to satisfy an emotional craving. Angier even allows Borden (one of the twins, anyway) to endure a trial, imprisonment, and execution. After Borden discovers Tesla’s machine in the trap room, with a copy of Angier locked inside, drowning, Cutter arrives on the scene and assumes Borden has trapped Angier. Neither of them suspects the disturbing reality: that Angier sacrifices a version of himself, possibly even his actual self, night after night.

Because The Prestige has submerged itself in the fixated missions of these two illusionists, the women in their lives feel underdeveloped—a common and fair criticism of Nolan’s output. The director never adequately confronts the inherently creepy nature of Borden and Fallon’s relationship with Sarah, each taking turns playing her husband. In another director’s hands, Borden’s dynamic with Sarah would be the premise of an unnerving identical twin film akin to Dead Ringers (1988). Sarah senses that there’s something wrong with her husband. Sometimes when her husband declares his love, it’s true; other times, as she observes, “Not today.” One brother loves Sarah; the other prefers Olivia (Scarlett Johansson), Angier’s assistant who switches sides. While Sarah’s eventual depression, alcoholism, and suicide in response to her husband’s seemingly split personality feel like afterthoughts to the central competition, Olivia is a plot device rather than someone who exists organically within this world. She also has no arc and disappears from the film without ample closure for her character. These are secondary concerns for Nolan, who often makes films about obsessives who commit to a philosophy or an idea and make all other relationships in their lives secondary—see Following (1998), Memento (2000), Inception (2010), the Dark Knight trilogy, and Oppenheimer.

Besides the duality of Angier and Borden, their shared obsessions, and themes of twins and doubles, an extratextual duality exists around The Prestige in its similarities to The Illusionist, another film about turn-of-the-century magicians released earlier in 2006—this one directed by Neil Burger and starring Edward Norton, Paul Giamatti, and Jessica Biel. Both involve skilled magicians who use their talents for all-consuming pursuits; both offer little dimension to their female characters; both are handsomely mounted productions, sparing no expense on sets, costumes, and production values. The Prestige remains superior for how Nolan once again weighs the fallout of obsession: suicide, physical violence, wrongful execution, and repeated self-annihilation. But unfortunately, both films rely on a ham-fisted device of explaining the finale by flashing back to earlier footage to remind the viewer of the clues they missed—a technique popularized by the lazy-if-effective ending of The Usual Suspects (1995) to reveal the film as an elaborate Keyser Söze lie. If Nolan’s use of this technique isn’t so blatant as Burger’s, it’s no less pandering.

Even without that montage finale, Nolan disrupts the emotional integrity of his ending for the viewer with a post-text choice. The Prestige’s chilling last shot shows Angier drowned in a tank, an image the viewer saw earlier, but now with the full scope of Angier’s self-destructive agenda in mind. The image might have lingered and even haunted the viewer. Instead, without skipping a beat, the credits roll, and Thom Yorke’s “Analyse” echoes on the soundtrack. It’s clear why Nolan chose the song—its lyrics speak of “playing a part” and having “no time” to “make sense” or “think things through,” which are on point for Nolan’s desire to create a puzzle of a film and encourage the audience to assemble its pieces. However, the sudden shift from an early-twentieth-century mindset to a contemporary song provides a jarring and ungainly anachronism in a film otherwise immersed in its period setting. Rather than allow the viewer to sit with the final image in silence or consider its implications with some moody period-appropriate music from David Julyan’s score, the Yorke song betrays the moment and neutralizes its lasting power. This ungainly jolt has always bothered me and always left me with a lingering sour taste about the otherwise engaging experience.

A scene early in the film has Borden alleviating Sarah’s concern about how a dangerous bullet catch trick is accomplished by revealing its secret. “Once you know it’s so obvious,” she remarks dismissively after he shows her the simple solution. Watching The Prestige a second time is a similar experience. Once the viewer knows how Nolan’s cinematic puzzle fits together, the wonder is gone. Instead of improving or revealing new dimensions with each new viewing, it becomes a flatter film, best appreciated for the surface-level details of the production: the two excellent performances by Jackman and Bale, the splendor of its visuals, and the thematically intricate symbolism. However, the potency of the dramatic turns and their emotional wallop are so closely tied to the puzzle quality of the film’s structure that they prove less effective after Nolan reveals his tricks. Regardless, it’s easy to see what draws Nolan to this material. A filmmaker of his caliber is a twenty-first-century magician, using craft, artistry, and science to create a smoke-and-mirrors show best reserved for a single sitting. Beyond that, Nolan reveals himself to be an expert craftsman with a fascinating, unconventional approach to narrative structure. If The Prestige is a disappointment on another viewing from an audience perspective, it’s also worth investigating, like trying to understand how a master magician has accomplished his illusion.

(Note: This review was originally commissioned and posted to Patreon on May 25, 2024. Thank you, Cooper!)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review