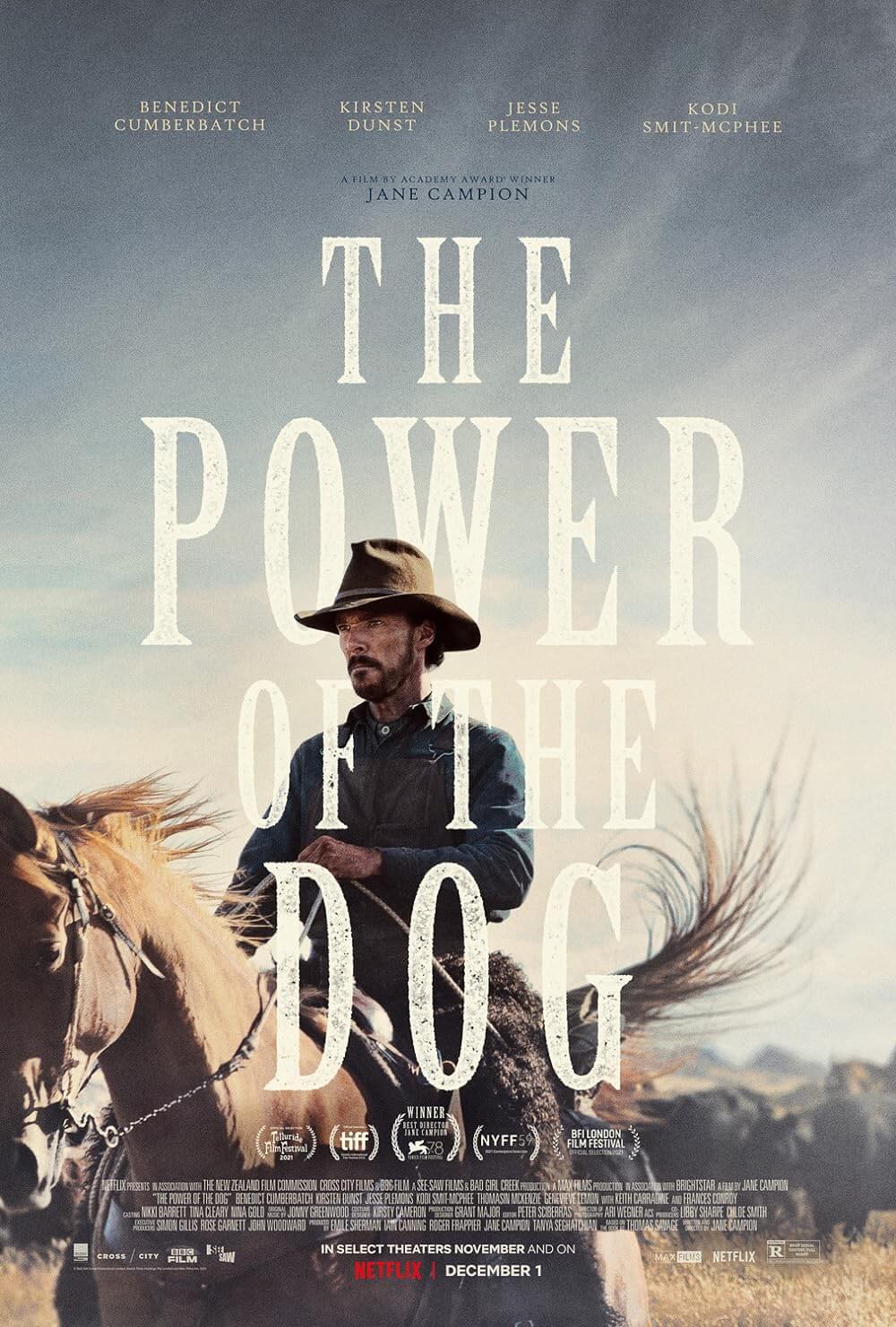

The Power of the Dog

By Brian Eggert |

The Power of the Dog is Jane Campion’s reconsideration of the American West and its hypermasculine archetypes. The story takes place in Montana, in 1925, well after the conquering of the frontier and mythologizing of the era’s legendary figures. It follows Phil Burbank (Benedict Cumberbatch), an angular and spartan rancher who throws insults with the same neutering effect as his bare-handed bull castration. Phil’s inward and gentle brother, George (Jesse Plemons), in many ways his brother’s opposite, is a rounder and softer sort of man who endures Phil’s bluster. The two have maintained the same dynamic for years: They have an equal say in their family’s successful cattle business, only Phil barks orders a little louder than his brother. Their equal partnership includes sleeping in the same room in separate beds, like a married couple in an old movie. Campion explores Phil’s relationships with others, each marked by his atmosphere of oppression. Some feel silenced or intimidated by his posturing; others have less predictable reactions. Most of these relationships begin with layers of subtext, and the narrative gradually peels away those layers to lay bare traditional models of male identity.

Campion treats her Western psychodrama differently than her more ponderous works of feminist filmmaking like An Angel at My Table (1990) and The Piano (1993). Instead, it’s a film of direct and surgical precision, her scalpel sharpened by her TV miniseries Top of the Lake (2013) and its 2017 follow-up. Rare for a Campion film, The Power of the Dog features predominantly male actors, and Phil’s presence makes it feel strident and raw. The first sign of Phil’s monstrous behavior comes in his casual nickname for his brother: “Fatso.” After a successful cattle drive, Phil and George treat their men to a meal at the local inn. Rose (Kirsten Dunst), a widow, prepares the meal, and her son Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee), a gangly, pale, and effeminate boy, helps serve. Phil almost does a double-take at Peter’s appearance, then proceeds to mock his slight lisp and the paper flowers Peter made to adorn the tables. Phil tells Peter to “get human” and later gives him the nickname “Miss Nancy.” But the “suicide widow and a half-cooked son,” as Phil describes them, soon become fixtures in the Burbank home. George and Rose marry, despite Phil’s written protestations to their parents, affectionately dubbed the Old Lady and the Old Gent (Frances Conroy and Peter Carroll). In one scene, Phil tries to remind his brother of the prostitutes they shared as adolescents, how women were objects then, and Rose is just another of them. George doesn’t listen. For Phil, George’s sudden romantic interest in a woman represents a betrayal.

Johnny Greenwood’s acoustic guitar accents the paranoid scenes where George courts and marries Rose, capturing how Phil twists with jealousy. It’s another brilliant score by Greenwood, bringing out the menace and torment in every interaction between Phil and his brother’s new family—who move into the ornate Burbank home, filled with wood walls and ominous animal heads. Beyond the score, music plays a vital role in The Power of the Dog. Phil plucks his banjo with baleful impatience, stewing over his desperate need to maintain control of George. There’s a slight panic in his eyes when he finally realizes he lost some part of George to Rose. His subsequent attack on Rose begins when she moves in, and he denounces any familial relation. Then George buys her a baby grand piano, hoping she will play for an upcoming dinner party. Rose, no pianist and struggling to practice, feels Phil nearby, signaled by the faint sound of his banjo echoing her piano keys. It’s a punishing scene, as Campion places the camera from what Rose imagines to be Phil’s presence, ratcheting ever closer, as if he were about to catch her in the act of failure. Finally, he humiliates Rose and frays her nerves beyond repair by playing the song’s notes over her. When the time comes to perform for her in-laws and the governor (Keith Carradine), she’s too shaken to press her fingers to the keys.

Johnny Greenwood’s acoustic guitar accents the paranoid scenes where George courts and marries Rose, capturing how Phil twists with jealousy. It’s another brilliant score by Greenwood, bringing out the menace and torment in every interaction between Phil and his brother’s new family—who move into the ornate Burbank home, filled with wood walls and ominous animal heads. Beyond the score, music plays a vital role in The Power of the Dog. Phil plucks his banjo with baleful impatience, stewing over his desperate need to maintain control of George. There’s a slight panic in his eyes when he finally realizes he lost some part of George to Rose. His subsequent attack on Rose begins when she moves in, and he denounces any familial relation. Then George buys her a baby grand piano, hoping she will play for an upcoming dinner party. Rose, no pianist and struggling to practice, feels Phil nearby, signaled by the faint sound of his banjo echoing her piano keys. It’s a punishing scene, as Campion places the camera from what Rose imagines to be Phil’s presence, ratcheting ever closer, as if he were about to catch her in the act of failure. Finally, he humiliates Rose and frays her nerves beyond repair by playing the song’s notes over her. When the time comes to perform for her in-laws and the governor (Keith Carradine), she’s too shaken to press her fingers to the keys.

Campion’s film is based on a 1967 novel by Thomas Savage, a closeted gay man who wrote Western fiction. Savage’s inspiration came from his upbringing on a farm in Montana, and he regularly wrote about life on the ranch while challenging traditional motifs. In her adaptation, Campion shows Phil overseeing the ranch in his chaps and spurs, occasionally venerating the late Bronco Henry, a cowboy and frontier legend he refers to as “the wolf who raised us.” Bronco Henry taught Phil how to ride horses, make rope out of hyde, oversee the ranch, and generally be a man. Phil tells grandiose stories about Bronco Henry, his wise ways, and his instruction. Among them, he considers a nearby mountain range and claims to see something there. His loyal ranch hands don’t see it, and they speak amongst themselves of Phil’s rare talent to see what they cannot. When he asks Peter to look, hoping to establish his superiority in the same manner that Bronco Henry did him, Peter only needs a second before he identifies the shadow that looks like a dog. But how could someone so fey as Peter see what only men of superior manliness and intelligence see? The Power of the Dog demystifies Western ideals and, as the film progresses, reveals them to be false fronts.

Indeed, Phil could be described as a “man’s man,” but he doesn’t follow the rugged male archetype. Doubtless, Campion had this in mind when she cast Cumberbatch, who doesn’t have the singular screen persona of John Wayne or Clint Eastwood. The character doesn’t partake at a local brothel alongside his men, nor does he engage in the ranch hands’ communal bathing ritual. Instead, we come to learn he is more complex than he seems, having studied classics at Yale to some aplomb. He has chosen a life of ranching and the accompanying characteristics. For instance, he takes pleasure from refusing to wash for George and Rose’s dinner party, wielding his stink like a badge of honor but also a protective layer to keep others away and from looking too closely. But all of his swagger and bullying give way to his intimate, private scenes. Campion follows him to a secret hiding place where he can be alone and bathe, naked—a word uttered in a scene between Phil and Peter later on, making it sound salacious. Phil is not merely a nude figure bathing in these scenes. His nakedness is both literal and figurative, leading to a sequence where he adorns himself with a cloth monogrammed with the letters “BH,” which he hides down the front of his pants. To be sure, it’s more apt to describe Phil as a man who, not unlike his idol, adopts the persona expected of him and forces that persona onto others, perpetuating a cycle of toxic masculinity and defining an era of American history. In doing so, he buries his sexuality.

Similarly, Peter is not what he seems. Although sensitive and inward, gawky and gaunt, Peter studies to become a surgeon, like his late father who committed suicide. When he returns home for the summer, he finds Phil has put Rose into a state of emotional ruin and alcoholism. In helping him acclimate to ranch life, Rose doesn’t do her son any favors when she buys him white, brand-spankin’-new cowboy duds fit for Roy Rogers. Ever the outsider, he spends most of his time exploring the land alone, where he catches a rabbit, seemingly to keep as a house pet. There’s a shocking moment when a house attendant (Thomasin McKenzie, in a curiously reduced role) peers over Peter’s shoulder to find he has dissected and splayed the animal on his desk for research. Meanwhile, Phil and his men snicker and mock the boy. But after Peter sees the dog shadow in the hills and finds Bronco Henry’s erotica, which Phil has kept and hidden away inside what can only be described as a child’s fort, the dynamic changes. Peter goes from staying out of Phil’s way to wanting his approval and instruction. He allows Phil to teach him to ride a horse and make a rope. Phil’s opinion of the boy begins to change as well. That Peter sees the dog shadow like Bronco Henry suggests that he, too, sees the world differently. Phil can’t imagine just how differently, leading to a dark outcome that feels almost too pulpy for what came before.

Similarly, Peter is not what he seems. Although sensitive and inward, gawky and gaunt, Peter studies to become a surgeon, like his late father who committed suicide. When he returns home for the summer, he finds Phil has put Rose into a state of emotional ruin and alcoholism. In helping him acclimate to ranch life, Rose doesn’t do her son any favors when she buys him white, brand-spankin’-new cowboy duds fit for Roy Rogers. Ever the outsider, he spends most of his time exploring the land alone, where he catches a rabbit, seemingly to keep as a house pet. There’s a shocking moment when a house attendant (Thomasin McKenzie, in a curiously reduced role) peers over Peter’s shoulder to find he has dissected and splayed the animal on his desk for research. Meanwhile, Phil and his men snicker and mock the boy. But after Peter sees the dog shadow in the hills and finds Bronco Henry’s erotica, which Phil has kept and hidden away inside what can only be described as a child’s fort, the dynamic changes. Peter goes from staying out of Phil’s way to wanting his approval and instruction. He allows Phil to teach him to ride a horse and make a rope. Phil’s opinion of the boy begins to change as well. That Peter sees the dog shadow like Bronco Henry suggests that he, too, sees the world differently. Phil can’t imagine just how differently, leading to a dark outcome that feels almost too pulpy for what came before.

Campion lends these characters empathy, even Phil, by directing superb and multilayered performances. Cumberbatch has rarely been better, presenting Phil as a carefully constructed and antagonistic façade, the microscopic cracks on which hint at the repressed feelings underneath. Dunst’s transitions from a shattered widow to tenderly lovestruck newlywed to a fraught alcoholic are among the most subtle and convincing turns in this actor’s career. Save for Melancholia (2011), it might be her best. Plemons, Dunst’s real-life partner, plays internalization achingly well, particularly in a scene where he steps away from his new wife for a moment, overwhelmed that he will no longer feel alone among such hardened men. Smit-McPhee, no stranger to the genre (see Slow West, 2015), also defies his character’s initial appearance, gradually revealing Peter to be far more aware and capable than he seemed. If there’s a flaw in the film’s construction, it’s not with the terrific performances. It has to do with the finality of the conclusion, which finds Peter dealing with his mother’s nemesis in no uncertain terms—a solution alluded to perhaps too often earlier in the film. When so much of the film relies on ambiguity and understatement, demonstrated when Phil touches Peter or shares his cigarette, the certainty, in the end, feels somewhat limiting. Still, Campion’s screenplay avoids spelling out what happens in the dialogue, relying on the viewer to make assumptions from clear visual input.

Shot in Campion’s native New Zealand, the film has an otherworldly look. Although the standard dusty trails and jagged mountains fill out the Western setting, they appear more expressive, their color manipulated by cinematographer Ari Wegner to almost fantastical heights. Lofty aerial photography zooms over the landscape, making The Power of the Dog feel like it takes place in a wondrous exaggeration of the American West—a landscape where legends are made. The filming of the landscape is even more pronounced and reflective of its characters’ emotional states than an Anthony Mann picture, such as The Naked Spur (1953) and Man of the West (1958). However, Campion’s restraint in portraying the exact natures of her characters serves the material well, reminding the viewer that the myth of the West derives from a front that conceals desires and represses individuality. Accented by Greenwood’s epic yet hauntingly rhythmic score, Campion’s astonishing film uses the West to explore how the world sometimes forces people to construct a safe and well-understood identity to satisfy others. In beautiful, disturbing, and confronting ways, The Power of the Dog compels viewers to see beyond the surface and recognize that people can be optical illusions—a double image hidden in plain sight.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review