The Post

By Brian Eggert |

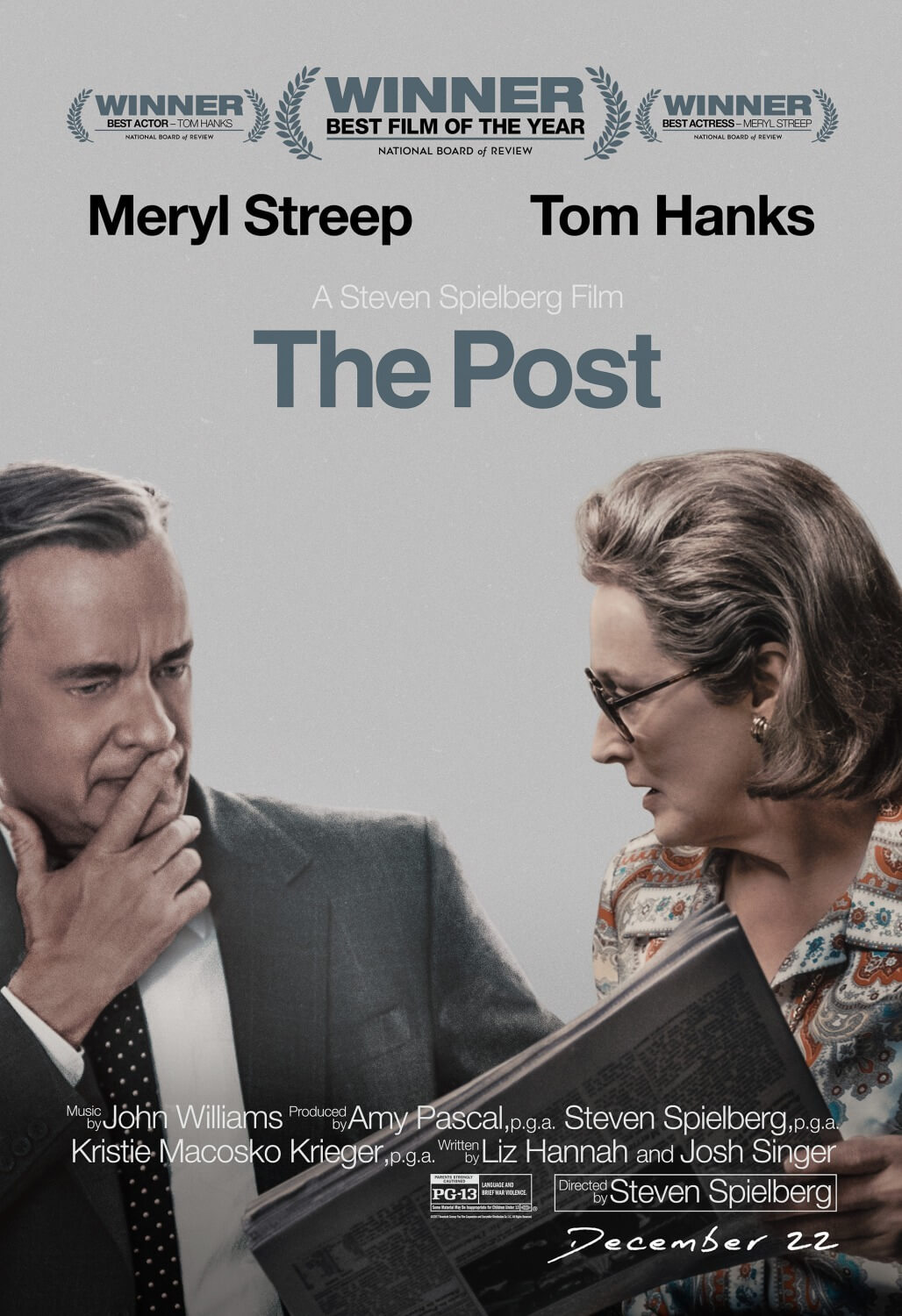

In his strain of historical films, Steven Spielberg has searched for moments in history where humanity emerged better for the lessons learned, regardless of how atrocious the conditions of the instruction. Humanity grows from Oscar Schindler’s example; from the sacrifices on D-Day; from the racist laws on which America allowed slavery; from Lincoln passing the 13th Amendment to the Constitution; and from the peaceful negotiation of a captured spy exchange between the Cold War enemies. With The Post, the director creates a vital lesson for the present by establishing a parallel to the past. The film is about The Washington Post‘s daring decision to print the Pentagon Papers in 1971, leading to a Supreme Court ruling that reinforced the First Amendment. Angry that journalists had dared criticize his administration, Nixon had attempted to control what journalists wrote about him by making thinly veiled attacks on the credibility of the news media, going so far as to order illegal wiretaps on reporters. The modern-day parallels are unavoidable. The Post responds to the political zeitgeist, while also reflecting feminist and journalistic issues under the Trump administration. To call this film of the moment would be a gross understatement. But more importantly, it’s another deftly entertaining Spielberg film.

Not long after the Trump regime took power, Spielberg received a script from first-time screenwriter Liz Hannah about the Pentagon Papers. It didn’t take long to see that the material was vital for today. Rushing into production, the director assembled his usual technical crew and a cavalcade of Hollywood’s best to complete the picture in a brief, nine-month schedule, demonstrating his famed efficiency and considerable clout. Who else but Steven Spielberg could convince arguably the two most well-known, well-liked, most talented and iconic performers working today to star on such short notice? Tom Hanks and Meryl Streep lead the film alongside a who’s who of today’s best character actors: Bruce Greenwood, Bob Odenkirk, Michael Stuhlbarg, Sarah Paulson, Carrie Coon, Jesse Plemons, and Bradley Whitford to name a few. The director’s usual composer, John Williams, provides a romantic and urgent score that carries the film along with an almost airy intensity. Janusz Kaminski once again serves as Spielberg’s director of photography, making every shot a cinematic feat that dazzles the viewer with Steadicam movements, saturated light, and extended takes—despite the material being rooted in decidedly non-cinematic conversations and journalism. Instead, this is one of the most visually engaging films in Spielberg’s recent career; he captures the bustling energy of a newspaper room from this era and does so with an unlikely formal bravado.

Set in 1971, the film involves The Washington Post‘s editor Ben Bradlee (Hanks, excellent) trying to secure a scoop by getting his hands on the Pentagon Papers. A top-secret Department of Defense study of the U.S. political and military presence in Vietnam, the 7,000-page report covered a period from 1945 to 1967 and detailed how every presidential administration from Truman onward seemed to know any victory in Vietnam was impossible. Nevertheless, the U.S. government, advised by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (Bruce Greenwood), kept sending troops to avoid looking like a loser. Early in the film, military analyst Daniel Ellsberg (Matthew Rhys) recognizes the problem here and copies the report, providing portions to The New York Times. They’re the first to publish information from the Pentagon Papers in a series of front-page articles, and subsequently, the first to be slapped with a restraining order against them, arguing that further publication would pose a risk to national security. Meanwhile, in a spy-thriller subplot, one of Bradlee’s top journalists, Ben Bagdikian (Bob Odenkirk), thinks he may be able to contact Ellsberg to secure a copy of the report for The Washington Post. Once Bradlee’s team receives a copy, there’s the lingering question of how much trouble it will cause them.

Set in 1971, the film involves The Washington Post‘s editor Ben Bradlee (Hanks, excellent) trying to secure a scoop by getting his hands on the Pentagon Papers. A top-secret Department of Defense study of the U.S. political and military presence in Vietnam, the 7,000-page report covered a period from 1945 to 1967 and detailed how every presidential administration from Truman onward seemed to know any victory in Vietnam was impossible. Nevertheless, the U.S. government, advised by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (Bruce Greenwood), kept sending troops to avoid looking like a loser. Early in the film, military analyst Daniel Ellsberg (Matthew Rhys) recognizes the problem here and copies the report, providing portions to The New York Times. They’re the first to publish information from the Pentagon Papers in a series of front-page articles, and subsequently, the first to be slapped with a restraining order against them, arguing that further publication would pose a risk to national security. Meanwhile, in a spy-thriller subplot, one of Bradlee’s top journalists, Ben Bagdikian (Bob Odenkirk), thinks he may be able to contact Ellsberg to secure a copy of the report for The Washington Post. Once Bradlee’s team receives a copy, there’s the lingering question of how much trouble it will cause them.

Perhaps more central to the profound emotional sweep of the narrative and its themes, the film also considers how the choice to publish falls on the newspaper’s publisher and owner, Katharine Graham (Streep, whose greatness in the role is not immediately apparent). Graham lived in the shadow of her father, Eugene Meyer, who bought The Washington Post in 1933. When her father died, he left the paper to her husband, Philip Graham. And when her husband died in 1963, she took over, much to the chagrin of the stuffy, all-male board of directors—Bradley Whitford represents the board’s primary opposition to female leadership. The board watches as Graham ushers her “father’s company” into a public one. At the same time, the decision to publish is tricky, as it could put the business’ initial public offering in jeopardy, which in turn threatens the financial security of the paper. It’s even more complicated because she’s longtime friends with McNamara. But more than that, Graham’s agency is at risk. For nearly a decade she has coasted along, maintaining the integrity of their relatively small newspaper but without much daily oversight; for that, she relies on Bradlee and her fellow board member and advisor, Fritz Beebe (Tracy Letts). But if she wants to run her paper, truly, she has to take ownership and responsibility.

Setting aside the history lesson, Spielberg also makes his most female-centric picture to date (take that, Elizabeth Banks). As Bradlee demonstrates, one might be tempted to question why Graham, a privileged member of the upper-class elite, emerges the hero in this story. In all, she merely approves the decision to publish, which is the right thing to do for journalistic integrity, not to mention America. Was it really that difficult a choice? It was Bradlee’s team that secured the document for their paper and wrote the story. But as Bradlee’s artist wife, Tony (Sarah Paulson), explains in a superb, eye-watering monologue, Graham’s choice is an act of bravery that sets aside the paper’s patriarchal legacy for her own. Perhaps it goes without saying, then, The Post is also about strong women taking a stand for themselves. Many of them look to Graham as an icon of what strong women can do in a male-dominated field. Streep leads them with a complicated performance bound by uncertainty and liberated by newfound conviction. It’s a dramatic arc that anyone could predict (this is, after all, history), and yet her character’s moments are no less affecting given our foreknowledge.

Of course, The Post might stand as a pseudo-prequel to Alan J. Pakula’s timeless thriller, All the President’s Men (1976), based on the book by The Washington Post‘s own Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward, respectively played by Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford. The Post contains a final scene that acknowledges the Watergate scandal, which the paper covered under Graham’s leadership, giving way to Nixon’s eventual resignation. Nixon had threatened Constitutional law to bolster his reputation and, as Bradlee observes, when a president tries to control what journalists can write, their tyranny becomes un-American. “The Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy,” announces Carrie Coon’s reporter. “The press was to serve the governed, not the governors.” Spielberg takes these historic words from the mouth of Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, who ruled on the Pentagon Papers Supreme Court case, and gives them to a woman, who relays them to her colleagues in a quiet and still newsroom. Meanwhile, President Trump, amid accusations of “fake news,” a host of women alleging sexual misconduct, and barring certain media outlets from the White House press room, has threatened to change libel laws so that he can sue journalists that don’t approve of his dangerous manipulations and rhetoric.

Unquestionably, Spielberg’s film is a cautionary tale that takes a stand against Trump and his patriarchal legacy, and the director wants everyone in America to receive his message loud and clear. Given the inclusion of Hanks and Streep, both marvelous, along with its cumulative high-profile status, the film has been designed to draw the most attention possible. As a result, people opposed to any anti-Trump talk will see Spielberg’s work as a product of left-leaning politics, and some may call The Post unforgivable for using a Hollywood film to take such a stance. That’s the culture war talking. The Right is going to continue to accuse the Left, backed by a mostly liberal Hollywood elite, of biases. But The Post is not a work of leftism. As with his other political films, Spielberg searches for an American ideal that, through an imperfect record fraught with humanitarian and political crimes, helped establish the country as a land of freedom—freedom against discrimination, freedom of social equality between all sexes and races, and freedom for the press to behave as intended, as watchdogs to ensure the government does not abuse its power. In that sense, Spielberg uses his considerable talent, and that of his outstanding cast, to tell an American story about our history, and this very moment.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review