The Piano Lesson

By Brian Eggert |

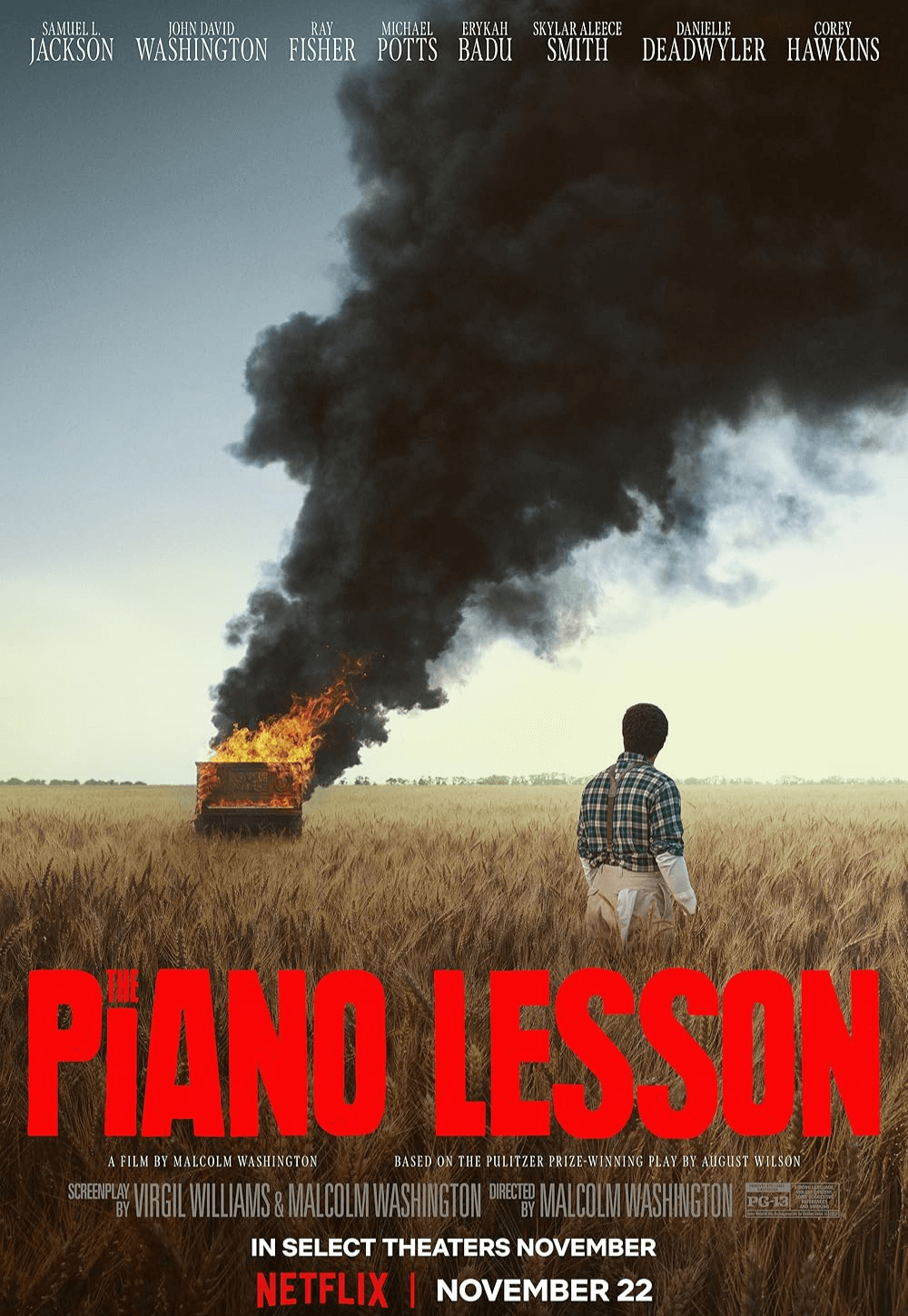

Denzel Washington continues his project of producing screen adaptations of playwright August Wilson’s Pittsburgh Cycle with The Piano Lesson, the third of a proposed ten-film series. Each example in Wilson’s thematically linked plays considers the Black experience in a different decade, and the producer, with the support of Wilson’s estate, shows no pattern in selecting which installment comes next. First came Fences (2016), directed by and starring Washington, following a Pittsburgh family in the 1950s. Next came Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020), a vibrant and energetic film about the blues scene of the 1920s—and arguably the best of the adaptations so far. The Piano Lesson takes place in the 1930s and is even stagier than the previous Wilson films. Bringing his family into the mix, the producer taps his eldest son, John David Washington, to star and his youngest, Malcolm Washington, to make his directorial debut. Malcolm Washington also co-wrote the screen version with Virgil Williams (Mudbound, 2017), though it’s debatable whether this film, or any of Wilson’s plays, makes for great cinema. They’re inherently different mediums, and filmmakers often attempt to compensate for the constraints of the stage with the freedom of cinema.

How fitting that Washington and sons worked together on this film, given its interest in family, history, and generational conflicts. Central to the drama is the family piano—an object with a rich and complex history—stolen back in the first scene, set in 1911, in Mississippi, against a barrage of red, white, and blue fireworks on the Fourth of July. That distinctly American imagery gives way to another facet of the country’s identity when, after reclaiming a piano from the white Sutter home, Boy Charles (Stephan James) is visited by white men on horseback carrying torches. They burn down his home, but the piano has already been carried off in the night by others. Twenty-five years later, in Pittsburgh, Boy Willie (John David Washington) arrives at the home of his uncle, Doaker Charles (Samuel L. Jackson, behind an unconvincing fake mustache), where his sister Berniece (Danielle Deadwyler) lives. Determined to stop sharecropping and buy his own land, Boy Willie wants to sell the piano, even though his father died to reacquire it. “All that’s in the past,” he argues, resolving to sell his heritage to make something of his future.

With the family’s faces etched in the wood, the piano is a loaded symbol, carrying tales of history, slavery, and other ghosts—most of them told by Doaker. Jackson played Boy Willie in the original 1987 production of Wilson’s play. Here, he lends his magnetism to the storyteller role, imbuing the instrument with almost mythic importance. Since most of the narrative unfolds in a Pennsylvania home, where the piano ties the drawing room together, many scenes in The Piano Lesson involve characters telling stories and debating what comes next for the instrument. Among those involved are Boy Willie’s pure-hearted friend Lymon (Ray Fisher), the amusing Wining Boy (Michael Potts), and the ghost of James Sutter (Jay Peterson)—a specter who serves as a catalyst for the story’s spiritual reckoning. Indeed, the film culminates in an impromptu exorcism performed by a resident holy man (Corey Hawkins); however, the sequence is less interested in delivering scares than supplying a symbolic resolution (in a similar manner as Lee Daniels’ The Deliverance, another Netflix production from earlier this year).

While the dramaturgy remains sound, with the screenwriters capturing the weight and symbolism of Wilson’s play, the execution sometimes distracts from the raw emotional nerve at the center. Consider the leading man. As Boy Willie, John David Washington acts as though he’s on a stage, not in a movie, shouting every line to distracting effect, as though he had hundreds in the audience to reach. He is a larger-than-life actor anyway, but outside of BlacKkKlansman (2018) and perhaps Amsterdam (2022), he hasn’t lived up to his potential. The funny thing is, had he given the same performance on a stage, it would have been pitch-perfect. Director Malcolm Washington tries to resolve the stage-to-screen conflicts by conceiving cinematic flourishes with director of photography Mike Gioulakis. One such expressive touch is a high-contrast monochrome cutaway showing Sutter falling down a well. In a critical error, the film also takes the story outside the domestic space. While the excellent opener in 1911 adds much in visual terms, a trip to a nearby nightspot feels superfluous. The play’s single location inside the Doaker home may have given the production the quality of a filmic chamber drama, but maybe that’s what it needed to support Wilson’s story.

Of Wilson’s plays, The Piano Lesson and Fences earned him Pulitzer Prizes, and that prestige factor no doubt helped convince Denzel Washington to select this title for his latest adaptation. Unfortunately, this awards contender for Netflix is the weakest of the Wilson-Washington films so far, despite several terrific performances and some handsome production design. The writing is resonant, particularly concerning Boy Willie’s desperate search for an identity next to his father and other family members. The filmmaking has an earthy dramatic realism that, combined with distinctly literary dialogue, carries the theatricality of a stage production. Williams and Washington’s script never resolves that tension, neither in the writing nor the filmmaking, leaving The Piano Lesson feeling like a missed opportunity. Among the few moments that find a balance is when several of the characters burst into a performance of “Berta, Berta,” a song about resistance and survival that, like the piano, links the past to the present. It’s a rare moment of genuine harmony and joy in the film, but it arrives early and has no equal in the remainder.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review