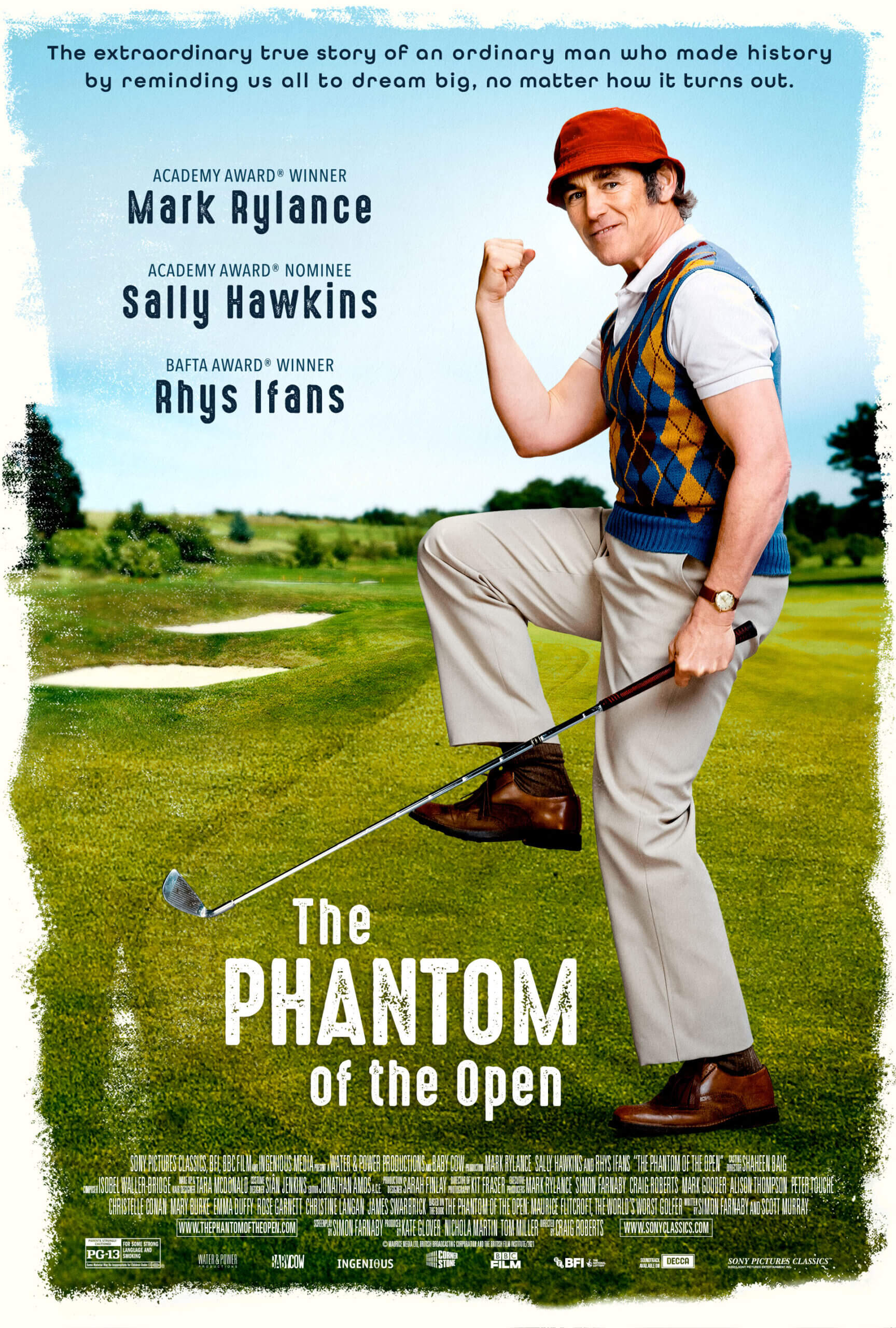

The Phantom of the Open

By Brian Eggert |

Note: This review was originally published for the 2022 Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival. Sony Pictures Classics will release the film theatrically on June 3, and in Minnesota on June 18.

In The Phantom of the Open, Maurice Flitcroft, a shipyard crane operator played by Mark Rylance, in his latest unassuming and affable performance, flips through television channels late at night. Before landing on a game of golf, which will become his destiny, Maurice briefly glimpses a scene from John Schlesinger’s Billy Liar (1963)—the classic wherein Tom Courtenay stars as a young working-class nobody who loses himself in elaborate fantasies. The inclusion signals Schlesinger’s film as an evident source of inspiration for director Craig Roberts when Maurice, hilariously entranced by a game of golf, drifts away into a reverie: The backdrop turns into a swirling Van Gogh dreamscape and the moon into a golf ball. Maurice climbs steps straight out of A Matter of Life and Death (1956) that lead to an elaborate tee, and once there, an enormous club swings and launches him on a journey around the planet. Roberts returns to this imagery to tell the surreal true story of how Maurice, a man who, in his late forties, having never shot a round in his life, found a way to compete in the 1976 British Open.

Written by Simon Farnaby and based on his 2010 book co-authored by Scott Murray, The Phantom of the Open combines two modish types of stories: There’s the based-on-a-true-story aspect, complete with real-life footage of Maurice Flitcroft during the epilogue, showing us how well the filmmakers replicated this stranger-than-fiction account of “the worst golfer in the world.” And then there’s the British comedy that pokes fun at elitists in the venerable British class system. Of course, everyone loves a David and Goliath story in which the underclasses get the better of the stodgy and privileged, especially the British, as recent movies such as Dream Horse (2020) and The Duke (2022) demonstrate. But such conflict remains standard in golf movies, and comedies such as Caddyshack (1980) and Happy Gilmore (1996) occupy the slobs versus snobs dynamic, underscoring the sport’s inherently elitist roots. And so, Maurice Flitcroft’s true story fits nicely into a cinematic format, delivering a healthy supply of belly laughs and tender moments to crowd-pleasing effect.

Contained in an interview framing device, Maurice tells how he proposed to Jean (Sally Hawkins), a woman with a child out of wedlock, and promised her a life of world travel, champagne, caviar, and diamonds. Nearly two decades later, after adding two identical twin boys to their family, Maurice hasn’t fulfilled his promise. Instead, they have contentedly settled into quiet domesticity, having passed on loftier opportunities to support their family. But with the eldest son Michael (Jake Davies) out on his own as an executive at Maurice’s shipyard, and the rambunctious twins (Christian and Jonah Lees) planning to take their disco dancing routine on a world tour, Jean gives Maurice license to explore his interests. Settling on golf, he invests in the cheapest set of clubs he can buy and naively applies to participate in the British Open, knowing next to nothing about the sport. When Jean fills out the entry form for him, she asks, “What’s your handicap?” Maurice replies, “Arthritis.” When she asks whether he’s a professional golfer or not, he confirms that yes, he intends to play professionally. No one on the entrance committee questions Maurice’s form because, as its snobby director (Rhys Ifans) insists, “No one would be so stupid to check professional if they weren’t.”

Rylance’s performance as Maurice Flitcroft might, initially, make the man appear ignorant or dim-witted. But, like his performances in Bridge of Spies (2013) and Don’t Look Up (2021), the actor speaks with a slow, intentional cadence that hides his intelligence. Maurice at first seems oblivious to the hierarchies and procedures of his new favorite sport, which results in humorous displays of his eccentricity and confused looks from the “tossers” at his local golf club. But Maurice reveals there’s more to him than meets the eye. When, after months of training on his own since the resident club refused to admit him, he debuts at the 1976 British Open, he casually converses in Spanish with a fellow golfer in the locker room. Despite shooting the worst round of golf in the Open’s history, he proves smarter than he looks and lives by a “love your mistakes” philosophy. Afterward, facing an embarrassed Michael and an enraged upper-crust that works to keep him out of every club in the country, Maurice becomes the “People’s Golfer”—a hero whose initial badness (he gets better) makes a mockery out of the elitist sport. “It’s called an Open,” he reasons in a letter to the director, “it should be open to everyone.”

Rylance’s performance as Maurice Flitcroft might, initially, make the man appear ignorant or dim-witted. But, like his performances in Bridge of Spies (2013) and Don’t Look Up (2021), the actor speaks with a slow, intentional cadence that hides his intelligence. Maurice at first seems oblivious to the hierarchies and procedures of his new favorite sport, which results in humorous displays of his eccentricity and confused looks from the “tossers” at his local golf club. But Maurice reveals there’s more to him than meets the eye. When, after months of training on his own since the resident club refused to admit him, he debuts at the 1976 British Open, he casually converses in Spanish with a fellow golfer in the locker room. Despite shooting the worst round of golf in the Open’s history, he proves smarter than he looks and lives by a “love your mistakes” philosophy. Afterward, facing an embarrassed Michael and an enraged upper-crust that works to keep him out of every club in the country, Maurice becomes the “People’s Golfer”—a hero whose initial badness (he gets better) makes a mockery out of the elitist sport. “It’s called an Open,” he reasons in a letter to the director, “it should be open to everyone.”

Besides an occasional dream sequence in Schlesinger territory, Roberts borrows techniques established in Martin Scorsese’s most urgent cinema. Cinematographer Kit Fraser and editor Jonathan Amos employ whip pans, zooms, and cracking camera flashes in the fluid, ever-moving camerawork, turning this modest story about golf into a fast-paced and visually active piece of filmmaking reminiscent of Goodfellas (1990) or Casino (1995). Roberts becomes the latest director to borrow these visual devices, along with a soundtrack of playful needle drops, in Scorsese reverence—Craig Gillespie borrowed them to similar effect for I, Tonya (2017) and Cruella (2021). Roberts uses them to ironic effect given the lower stakes of the story, but that doesn’t mean The Phantom of the Open doesn’t genuinely tug on the heartstrings. Hawkins, who starred in Robert’s last film, 2019’s Eternal Beauty, has a profound presence by the third act, serving as Maurice’s rock and staunchest supporter. As a part-time theatre company costumer, she designs the disguises Maurice uses to sneak into subsequent tournaments under false names. Likewise, the father-stepson relationship begins with an embarrassed Michael shaming his father for pursuing his dreams so late in life. How dare he. Inevitably, they reconcile in a grab-your-Kleenex moment.

Although it would be easy (and callous) to condemn The Phantom of the Open for its conventional structure and evident pulling of heartstrings, Roberts and his excellent cast render a deeply felt underdog story about never giving up on your dreams. Maybe it’s too lighthearted for today’s cynical society, and perhaps it spends too much time considering the real-life Maurice at the end. But the setup is deeply relatable, as everyone has things they wish they had done but didn’t. Likewise, each member of the Flitcroft family makes compromises, choosing reality over their wildest ambitions because they have settled in some way or another. Maurice’s example becomes an inspiration for many inside his family and beyond, resulting in his unlikely international celebrity in some golfing circles. Evidenced by Isobel Waller-Bridge’s equally lithe and nimble score, this story packs a surprising amount of joy and emotion into its delivery. Even if the sport registers as dull and stuffy, moviegoers will find the film irresistible.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review