The Personal History of David Copperfield

By Brian Eggert |

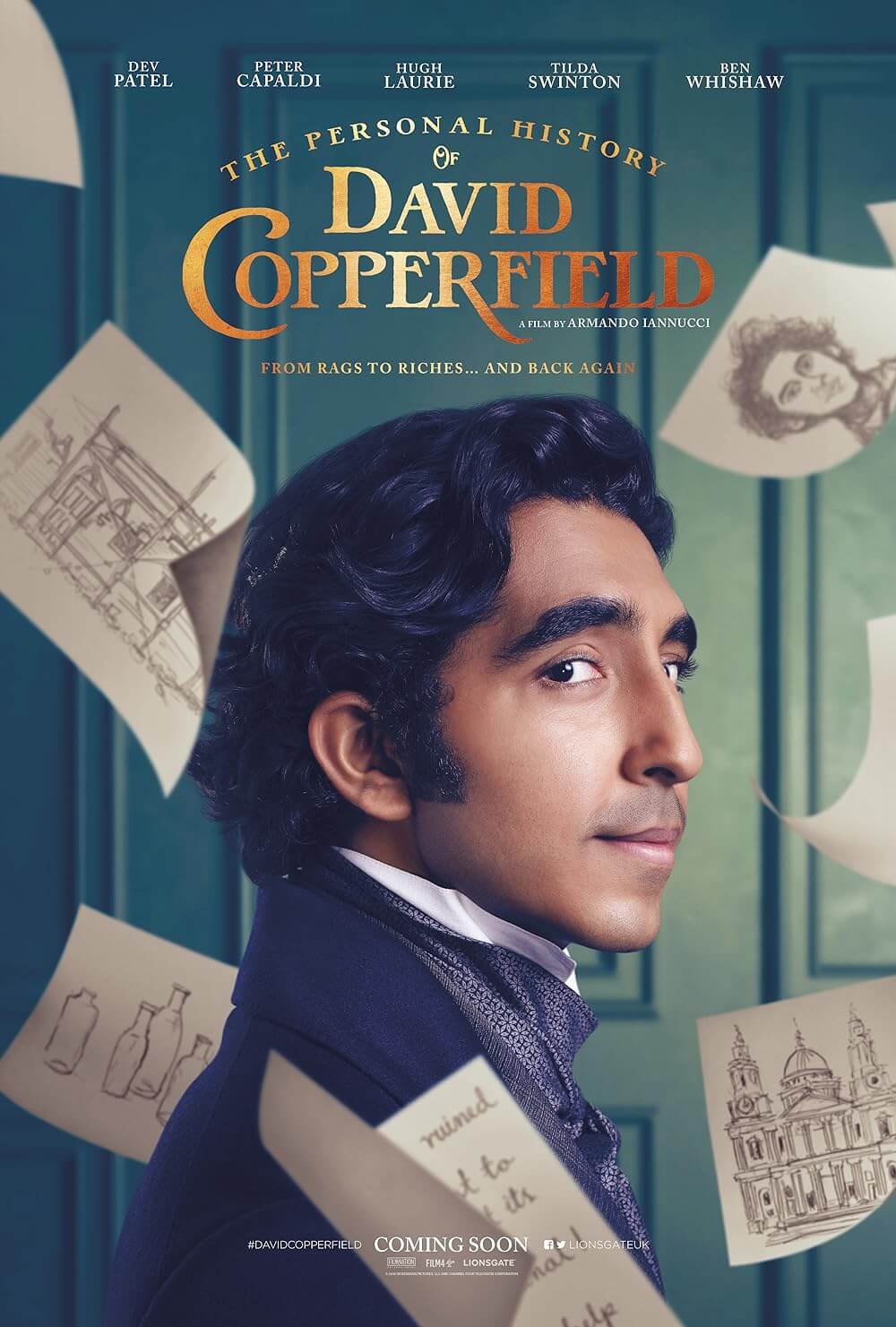

Armando Iannucci reinvigorates the work of Charles Dickens with The Personal History of David Copperfield, an urgent and richly postmodern take on the classic novel. No one would expect the Scottish comedian, satirist, and director to carry out another in a long line of stately and respectable adaptations. Iannucci isn’t the sort to color inside the lines. His version stars Dev Patel as Dickens’ adaptable protagonist, an enduring hero whose pliable youth gives way to a fully formed adult writer. Although it’s the model for countless stories of self-discovery, David Copperfield invites reinterpretation every few years, occasionally in film but more often in extended television miniseries, and almost always as a reflector of the present in new and invigorating ways. But it’s difficult to imagine a screen translation more vibrant and alive, from its rambunctious visuals to the sheer beauty of the images before us, from Iannucci’s inspired casting to the interest in language and wit he shares with the author. And if Alfonso Cuarón’s adaptation of Great Expectations in 1998, or even Carol Reed’s musical Oliver! (1968), proved that Dickens could survive a radical repurposing of the source material, Iannucci’s film shows how timeless and resilient the author remains. Sure enough, the film’s Victorian backdrop gives rise to a pressing look at class, poverty, and identity, albeit through a spirited and modern lens.

After more than a year of serialized monthly installments starting in early 1849, Dickens’ novel was published as a book in late 1850, under the name The Personal History, Adventures, Experience and Observation of David Copperfield the Younger of Blunderstone Rookery (Which He Never Meant to Publish on Any Account). It was vaguely autobiographical for the author, who had worked in a factory as a child and experienced many of the financial ups and downs of the story’s hero. For Dickens, the book celebrated an author’s necessary ability to watch the world, record those experiences in notes, and then shape them into a literary expression. This is true of Iannucci’s adaptation, which finds Patel’s take on the character scribbling memorable lines and behavioral ticks of those he meets onto bits of paper, or later, performing their mannerisms in the mirror. But Iannucci’s screenplay, co-written with Simon Blackwell, concerns itself with authorship less in a writerly sense than taking ownership of one’s identity. Write your own story, this film seems to say. And it’s a lesson explored not only in the protagonist’s journey to become a writer and his acceptance of himself under the name Copperfield, but it’s also hinted at in Iannucci’s casting choices.

Given the director’s earlier output, a rather optimistic Dickens novel might seem uncharacteristic for Iannucci, who’s best known for crafting hilariously vitriolic insults and skewering modern politics. After all, this is the creator of the BBC series The Thick of It (2005-2012), one of the most acerbic send-ups until its spin-off film, In the Loop, debuted in 2009. Then came HBO’s Veep (2012-2019), a show that even Capitol Hill politicians said resembled reality to depressing extremes. More recently, The Death of Stalin (2018) turned the horrific power-maneuvering after the Soviet leader’s demise into the stuff of riotous laughter, even while it proved grimly reflective of modern-day politics. Through his signatures—breathless wordsmithing, buoyant camerawork, relaxed performances, fluid pacing—Iannucci compresses and refines Dickens’ own favorite of his books into a rousing success. It contains dialogue lifted straight from the novel, blended with Iannucci-brand intelligence and sarcasm, and occasional silliness. Take the verbing of the word “kite,” or Morfydd Clark’s role as Dora, an intellectual latecomer who speaks for her dog in a goofy voice, or the visual gags that resemble silent film stunts. It’s all deliriously blended in a film that may require a second viewing to assess its cleverness properly.

The Personal History of David Copperfield draws inspiration from Dickens’ novel, of course, but also various modes of stage and cinema. When Patel’s David faces the crowd in the opening scene’s Victorian jewel-box theater, he reads aloud from his memoir with the book’s famous first lines—“Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else”—and visually transports the viewer into his past. Born to a single mother, Clara (also Clark), and the treasured family housekeeper, Peggotty (Daisy May Cooper), David begins life surrounded by warmth, and his gift for observation and mimesis is encouraged. But very quickly, his childhood begins to resemble Fanny & Alexander (1982): David’s stepfather, Edward Murdstone (Darren Boyd), and his imposing sister, Jane (Gwendoline Christie), arrive in the home, clad in black garb, and bring cruel discipline. In short order, the rebellious David finds himself in London, forced to work as a corker in a bottling factory. His banishment doesn’t come in the usual manner; Iannucci shows him swept away by an almost spectral carriage that seems to travel straight through his home on a miles-long oriental runner.

The Personal History of David Copperfield draws inspiration from Dickens’ novel, of course, but also various modes of stage and cinema. When Patel’s David faces the crowd in the opening scene’s Victorian jewel-box theater, he reads aloud from his memoir with the book’s famous first lines—“Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else”—and visually transports the viewer into his past. Born to a single mother, Clara (also Clark), and the treasured family housekeeper, Peggotty (Daisy May Cooper), David begins life surrounded by warmth, and his gift for observation and mimesis is encouraged. But very quickly, his childhood begins to resemble Fanny & Alexander (1982): David’s stepfather, Edward Murdstone (Darren Boyd), and his imposing sister, Jane (Gwendoline Christie), arrive in the home, clad in black garb, and bring cruel discipline. In short order, the rebellious David finds himself in London, forced to work as a corker in a bottling factory. His banishment doesn’t come in the usual manner; Iannucci shows him swept away by an almost spectral carriage that seems to travel straight through his home on a miles-long oriental runner.

Not every subplot or character from the book makes the cut into Iannucci’s film, but the breezy treatment captures David’s ever teeter-tottering circumstances. Sometimes the boy finds himself living in a storybook in the dreamlike fish market near the Peggottys’ capsized boat-home. Other times, he’s under Mr. Micawber’s (Peter Capaldi) care, who introduces David to the London streets, a land festering with creditors and other unsavory types. Tilda Swinton is at once motherly as David’s aunt, Betsey Trotwood, who has a donkey problem the same way some people have cockroaches. She lives with Mr. Dick, played by Hugh Laurie, who cannot create—the beheaded King Charles’ thoughts consume his mind—a blockage that David heals by attaching Mr. Dick’s notes to a kite and flying them in a form of therapy. At school, he meets James Steerforth (Aneurin Barnard), an elitist who reminds David that class and money doesn’t necessarily translate into good character. But the same is true of the meek; not all are innocent. Just look at the wormy Uriah Heep (Ben Whishaw), a humble if nosy servant who might earn our sympathy as the butt of cruel remarks by David and his schoolmates, except for his bitter and hateful turn.

Iannucci transitions from one scene to the next with delirium that some might mischaracterize as a crammed adaptation, while those versed with the director’s output will recognize his finesse, sophistication, and downright silliness. He’s a master of creating chaos and charting odd behaviors. Watch as Heep’s frumpy mother delivers a mountain-of-a-cake for tea, setting it onto her table with all the delicacy of a cinder block (“I like to know I’ve had a cake,” she says). Or watch Patel stride like a ballet dancer through the proctor’s library to avoid creaking floorboards—he has all the physical dexterity and comic timing of a Chaplin or Keaton. And notice the immediacy with which Iannucci captures the emotional heights, such as when young David evades a beating from Murdstone or rebels against his employer at the bottle factory. With equal amounts of comedy and pathos, Iannucci transitions from one life event to the next with sometimes merry, sometimes grave tonal fluctuations. It takes a receptive audience to roll with the shifting moods and contemporary style of acting on display, especially given its layers of humor and drama.

The same is true of the visual treatment, which finds cinematographer Zac Nicholson capturing scenes in an array of Gilliam-esque styles—complete with frantic close-ups and wide angles. Iannucci circumvents any Masterpiece Theater-style aesthetics for something more modern. It’s easily his most visually accomplished film; every frame is alive with experimentation and beauty. In a couple of outdoor picnic scenes, he captures the English countryside like an idyllic painting, brimming with color, sunshine, and wildflowers. Elsewhere, he uses jagged jump cuts, and he projects images from David’s mind onto a blanket or curtain like a home movie—which characters then see and observe. Although he employs convincing CGI to render the rebuilding of the House of Parliament and later a deadly storm, his treatment feels grounded. Similar to his approach to The Death of Stalin, the characters wear period-appropriate costumes (from designers Suzie Harman and Robert Worley) and inhabit convincing spaces. Production designer Cristina Casali creates a look that recalls something like The Grand Budapest Hotel (2015). These vivid colors, heightened in David’s youth, fade with time and perspective, so when he revisits these spots as an adult, they look muted. Free-wheeling though the visuals may sometime seem, there’s a distinct method at work.

The same is true of the visual treatment, which finds cinematographer Zac Nicholson capturing scenes in an array of Gilliam-esque styles—complete with frantic close-ups and wide angles. Iannucci circumvents any Masterpiece Theater-style aesthetics for something more modern. It’s easily his most visually accomplished film; every frame is alive with experimentation and beauty. In a couple of outdoor picnic scenes, he captures the English countryside like an idyllic painting, brimming with color, sunshine, and wildflowers. Elsewhere, he uses jagged jump cuts, and he projects images from David’s mind onto a blanket or curtain like a home movie—which characters then see and observe. Although he employs convincing CGI to render the rebuilding of the House of Parliament and later a deadly storm, his treatment feels grounded. Similar to his approach to The Death of Stalin, the characters wear period-appropriate costumes (from designers Suzie Harman and Robert Worley) and inhabit convincing spaces. Production designer Cristina Casali creates a look that recalls something like The Grand Budapest Hotel (2015). These vivid colors, heightened in David’s youth, fade with time and perspective, so when he revisits these spots as an adult, they look muted. Free-wheeling though the visuals may sometime seem, there’s a distinct method at work.

The purposeful casting and performances, too, adopt Iannucci’s form-follows-function method, which is also perfectly of the moment. Much has been made of Iannucci’s choices; however, just as in his opening scene, he draws inspiration from the stage with the theatrical tradition of colorblind and genderblind casting. Patel could not have been a better choice. Equally brilliant are Rosalind Eleazar as David’s loyal friend, Agnes Wickfield; Nikki Amuka-Bird (from Iannucci’s Avenue 5 on HBO) stars as the sharply classist Mrs. Steerforth; and Benedict Wong is genial as the ever-soused Mr. Wickfield. These choices fulfill the promise of Dickens’ text, which is interested in self-creation by exploring the limits of who can play what roles. Throughout the story, David goes by many names given to him by those he meets— Steerforth calls David by the nickname “Daisy,” and Dora names him “Doady.” He bends to their relabeling and even adopts the interests of those around him. But both Dickens and Iannucci explore how identity is more than a name or the label someone gives you; it’s something you discover and define for yourself.

If Dickens hoped to justify his own form of art with his story, then Iannucci uses the material for the same ends in The Personal History of David Copperfield, an uncommonly funny and playful take on a resilient book. However unlikely, Dickens and Iannucci find wonderful synchronicity; they both pour so much life into their respective art forms that they cannot help but feel alive in their own ways. Both the book and film are such acutely observed, generous outpourings, showcasing life’s many glories and downfalls. At the bottom, they present classism and hunger on the streets of Victorian London, but they also offer a protagonist who finally achieves personhood by seeing beyond class. Iannucci frames these ideas and revitalizes them by exploring the boundaries of his medium, making any attempt to draw straight comparisons between the adaptation and its source a pointless exercise. They have much in common, but this interpretation does not concern itself with faithfulness, only capturing the spirit of the thing using Iannucci’s toolkit of absurdity, humor, and self-reflexivity.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review