The Other Lamb

By Brian Eggert |

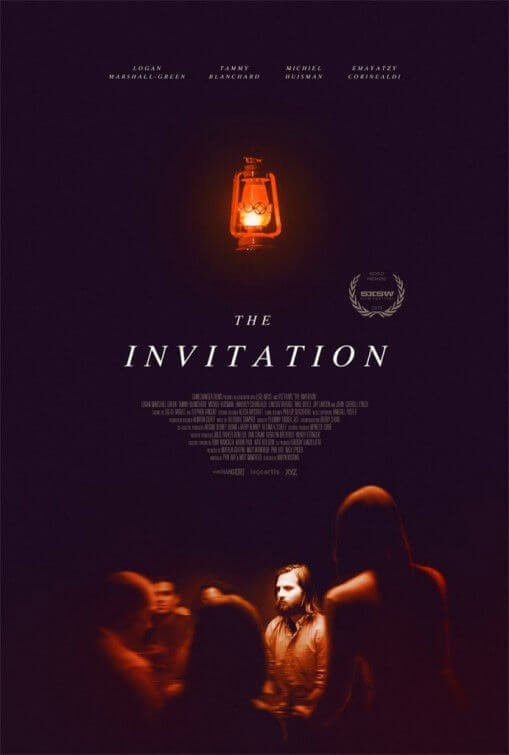

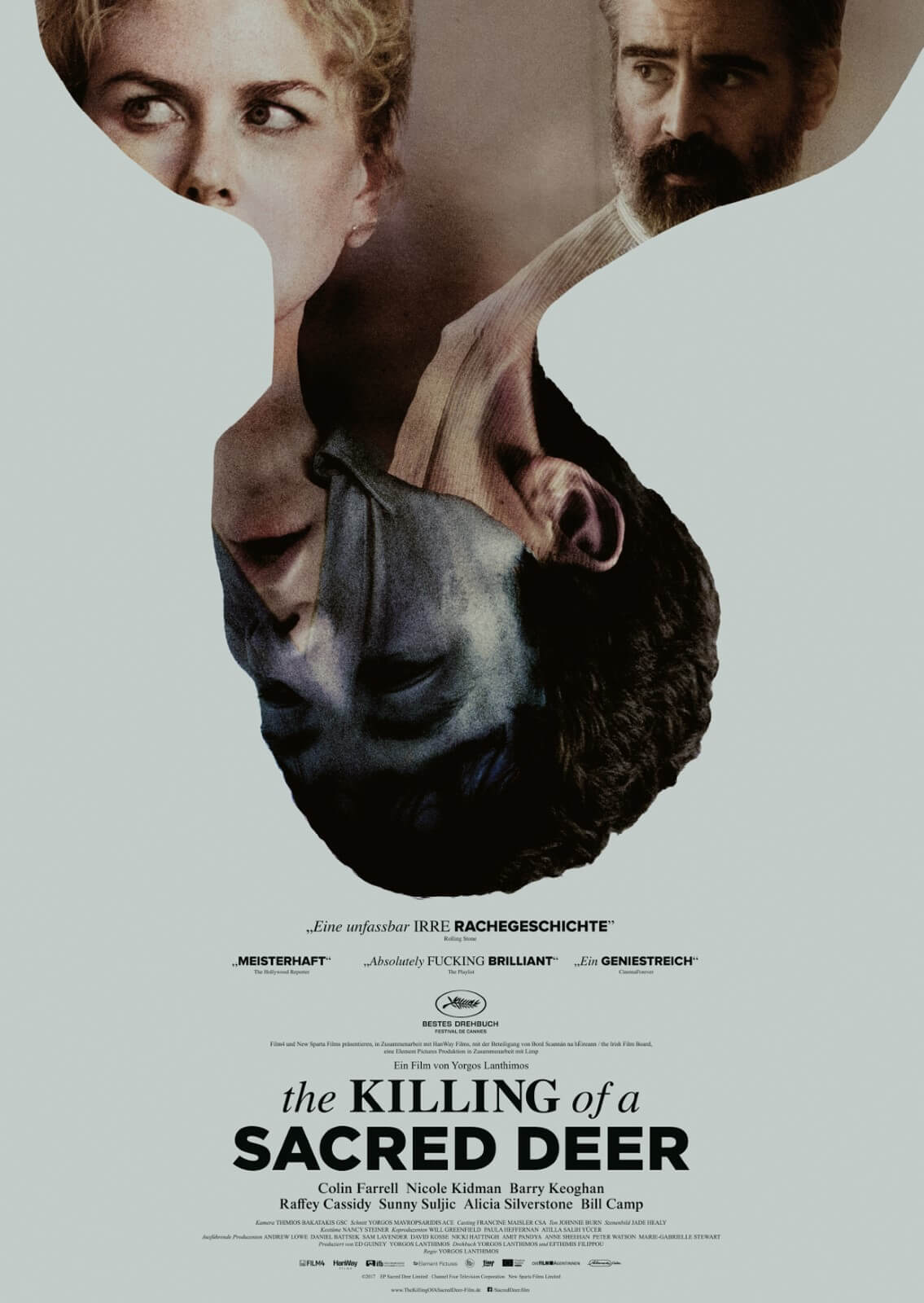

In The Other Lamb, Raffey Cassidy plays Selah, a teenager in a “flock” of daughters and wives that belongs to their self-appointed master, whom they call the Shepherd. The younger women like Selah wear blue dresses; the older wives wear a shade of red that sometimes looks purple. They sit on opposite sides of a long dinner table, at the head of which resides the Shepherd, played by Michiel Huisman, who smolders with charisma and dread, appearing downright Christlike with his beard and long hair—but it’s evident that he has more in common with Charles Manson. In a role that recalls his cult leader in The Invitation (2016), Huisman’s presence is almost on-the-nose casting, as is Cassidy’s. She’s best known from Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017), where she played the daughter in a family with mechanical, borderline ritualistic devotion to their paterfamilias, another in a series of the Greek director’s deconstructions of family dynamics. The Other Lamb feels like Polish filmmaker Malgorzata Szumowska and screenwriter Catherine S. McMullen have taken a Lanthimos family and resituated it in the realm of folk horror.

Set deep in the woods and, given their accents, somewhere in America, the film could be mistaken as a period piece reminiscent of something by Robert Eggers (The Witch, The Lighthouse). There’s an austere beauty in how d.p. Michal Englert shoots the colorful dresses against the surrounding earth tones and overcast skies. However, the flat glass and corrugated roof on their shelter suggest a contemporary period, as does the rundown trailer that dons a crude painting of the Shepherd. McMullen’s script offers only vague allusions to how the Shepherd plucked his flock from the real world and brought them here, although they must have survived like this for many years—some of the wives have been with him since the beginning, and he’s fathered many of the daughters. Their obscure Christian-based religion relies on the metaphor of a single ram leading a flock of sheep, and the omnipresent ram skulls and use of lamb’s blood in their rituals factor into their daily life. Elsewhere, the use of string creates weblike decorations overhead and an elaborate framework to an outdoor room, though the string’s symbolism is less clear. The flock prays to their Shepherd, thanking him for his love and the beautiful day. When their brainwashing polygamist asks, “Do you accept my grace?” they respond with “I do, Shepherd.”

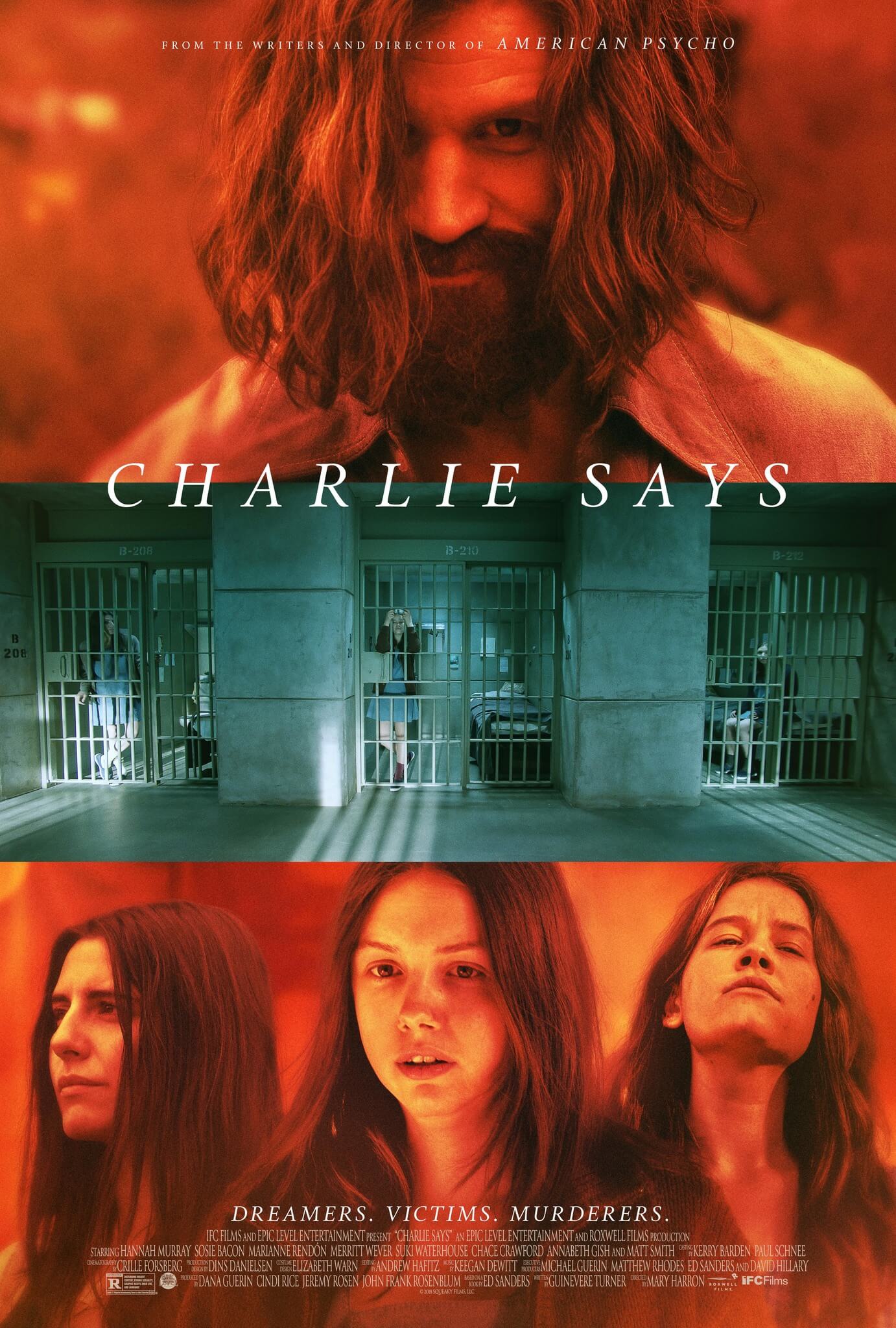

Films about cults, from Sean Durkin’s Martha Marcy May Marlene (2011) to Mary Harron’s Charlie Says (2019), show a process of breaking members down and building them back up again. By the time The Other Lamb opens, everyone has been thoroughly broken and reconstructed. The Shepherd showers his flock with praise, telling them, “You are perfect; you are accepted.” They perform in ceremonies involving animal sacrifice, with blood smeared on their faces, and they speak in tongues as if imbued with his (bogus) powers. The haunting quality of these scenes is staggering, as we know that a more disturbing layer to this situation will be revealed soon enough. “His attention is like the sun,” remarks Sarah (Denise Gough), one of the wives who has been sent into isolation as punishment, “bright and glorious at first. Then it just burns.” Hints at the Shepherd’s more insidious intentions come with his nightly selection for his bed-chamber. He grips the unlucky wife just as he grips the throat of a sacrificial lamb, and in an act of possession, he forces his fingers down her throat until she gags. The women have been told that their “most sacred duty” is about trusting what the Shepherd is putting into them.

Of course, the patriarchal Shepherd has demonized the female body as something unnatural, and menstruation is an “impure” time, during which a woman is cast out from the group. Selah’s first period is almost as traumatic as that of Carrie White—it coincides with the birth of a dying lamb, which she then proceeds to stab to death in a scene drenched in blood. Szumowska has framed The Other Lamb from Selah’s perspective, and it’s unclear whether certain scenes take place in her daily reveries or reality. The film often cuts away to dreams and nightmares, or maybe they’re Selah’s precognitive visions of women submerged underwater in white robes and a mythic waterfall. Later, Selah sees a station wagon on a road and a vision of herself riding in the backseat. The persistent wide-angle lenses make each scene feel even more phantasmic, bringing to mind moments from Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009). At any moment, we suspect a dead lamb will look into the camera and declare, “Chaos reigns.”

Ambiguous as details in The Other Lamb are, McMullen’s script also lacks restraint. Knowing from the outset that the story takes place today robs a later moment, when a police car shows up and tells the Shepherd to clear out, of its potential impact. With the arrival of authorities, the Shepherd’s capacity for self-aggrandizing bullshit approaches its zenith—the next day, he fakes a spell and claims to have an answer: the flock has to move. His hypocrisies and cruelty only become more pronounced on the journey by foot to a new Eden. Along the way, we learn what happens when babies of the wrong sex are born into the flock, and worse, what happens when he decides his wives have grown too old and should be replaced with his daughters. Even as the film grows more disturbing, it stays with Selah, whose character is mostly a witness to these events until her devotion is tested by the gradual degradation of the Shepherd’s facade.

Though this is a gorgeous looking and downright disturbing film, Szumowska breaks the containment and restraint midway through with the odd placement of a modern pop song, briefly spoiling the mood. Otherwise, Szumowska, in his English-language debut, relies on his performers striking an intimidating pose against a backdrop of sublime Nature. However magisterial these scenes may appear, their symbolism is obvious, and the characters who inhabit them feel one-note—including Selah, whose presence has been reduced to her hallucinations, as well as looking at various landscapes and bodies of water with a loaded expression. The outcast Sarah is the sole character who seems to have escaped the Shepherd’s control and realized that, whoever she is, she isn’t a member of his flock anymore, but the film doesn’t give her much to do. Moreover, the final scene that hints at freedom from the Shepherd may also mean the formation of another cult, suggesting the flock has once again gripped onto someone else’s idea of freedom. The Other Lamb features plenty of striking visuals and several convincing performances. Still, its stylistic approach keeps the viewer at an emotional remove, leaving us to admire the result with cold appreciation.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review