The Old Man & the Gun

By Brian Eggert |

If Robert Redford’s vow to retire from acting makes David Lowery’s nostalgic The Old Man & the Gun the Hollywood legend’s final film, then it’s a loving swan song. But a month after making such declarations to various media outlets in August 2018, Redford put distance between himself and his earlier statement, suggesting that he might have another role or two left in him. It’s unfortunate, in a way, because it’s difficult to imagine a production as devoted to capturing the spirit of Redford’s appeal, as well as the heyday of his celebrity. The Old Man & the Gun, about an aged criminal who just wants to keep doing what he loves, robbing banks, is an apt metaphor for Redford, an octogenarian actor who may or may not retire soon. Lowery’s sentimental story adopts the look and feel of those easygoing capers from Redford’s limelight, resulting in a film best suited to moviegoers attuned to relaxed, genial charms, instead of the usual abrasive spectacles of today’s cinema. It’s a pleasant, unobtrusive film made with affection for Redford’s legacy and style, but its airiness means that without Redford, it wouldn’t work.

Based on an article from a 2003 issue of The New Yorker by David Grann, Lowery’s screenplay romanticizes outlawism in a way reminiscent of Redford’s most rascally, iconic roles in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and The Sting (1973). The real-life bank robber Forrest Tucker, played by Redford, was ceaselessly agile, reportedly a looker, and relentless in his ingenuity. Having robbed north of 80 banks and escaped from prison more than a dozen times, Tucker leaped into a criminal lifestyle during his mid-teens and kept it going until his final robbery at the age of 79. Tucker distinguished himself by wearing clean suits and covering his face with a white ascot for a decidedly cartoon crook appearance, but he left a string of abandoned wives and loss behind him. He died in prison in 2004. Lowery reinvents the character, transforming Tucker into a quintessential Redford persona—a slick criminal who uses the actor’s enduring charm and good looks to his advantage. In scenes that recall George Clooney in Out of Sight (1997), Redford’s version of Tucker walks into banks, disguised only with a false mustache, grins at the female teller or bank manager, and politely asks them to hand over the loot. Who wouldn’t comply with that smile, even from the 82-year-old actor?

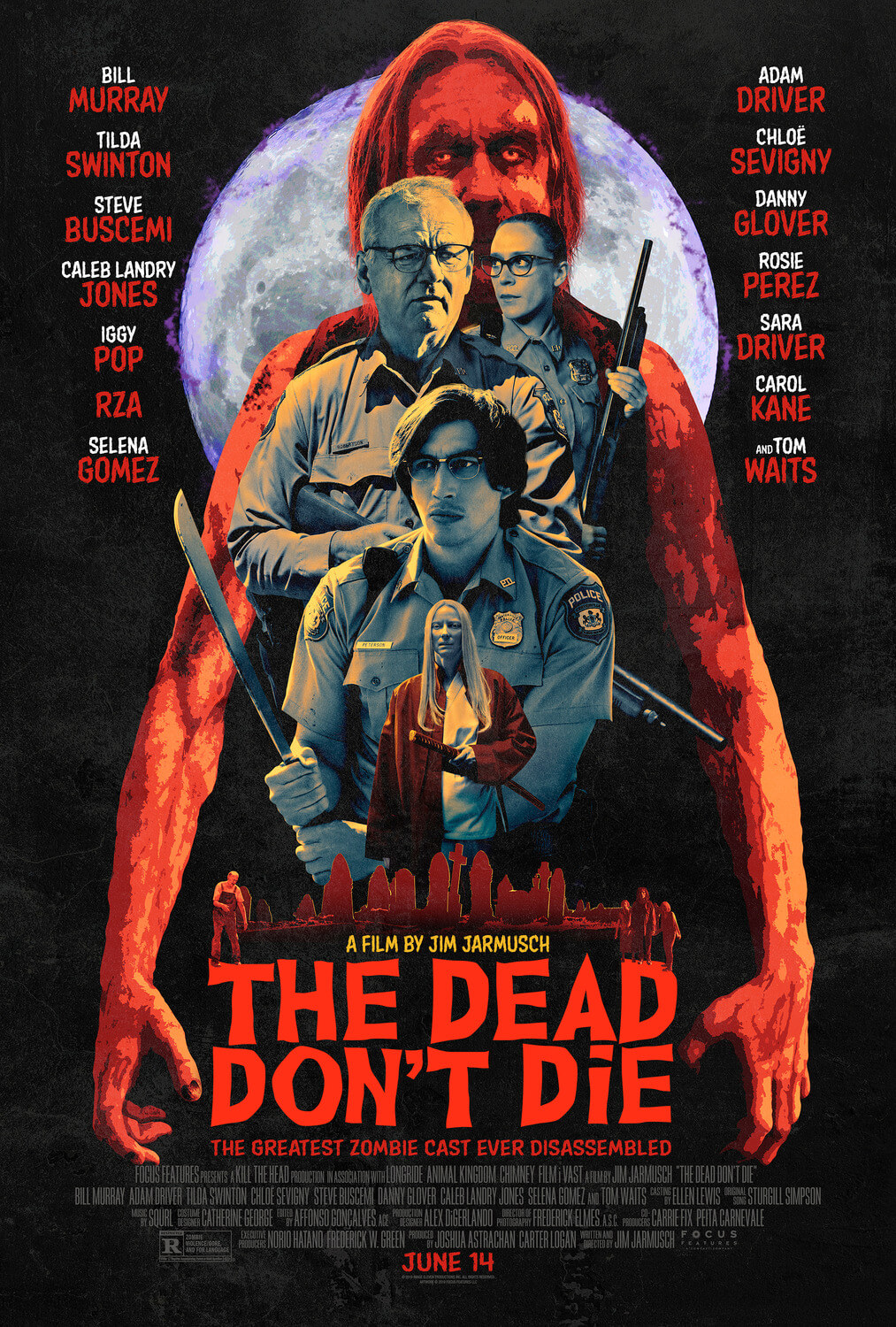

Joined by two accomplices, played by Danny Glover and Tom Waits, Tucker’s trio of elderly robbers earns the name “The Over the Hill Gang” after their cross-country pattern is spotted by police officer John Hunt (Casey Affleck). Hunt, an apt name for a detective, seems to admire Tucker’s way of life, as detectives most do in such cops-and-robbers stories. But unlike the lone wolf cops in other heist fare—Heat (1995) comes to mind—Hunt is a soulful family man, and Affleck plays him bemused yet determined by his present case. Elsewhere, Tucker meets Jewel (Sissy Spacek, herself a screen legend) during the film’s opening getaway sequence, and they form a casual, polite romance. A widow who lives on a farm with her dog and three horses, Jewel doesn’t believe Tucker when he admits to robbing banks for a living, but she’s not too concerned about the truth either. They get along well enough without the intimate details of their past lives spilling out, and their pleasant, comfortable time together amounts to the film’s most endearing scenes.

Lowery’s style removes any sense of thrills or suspense from the proceedings, concentrating entirely on a relaxed atmosphere rooted in an appreciation of past modes. Most of the robberies occur either off-screen or through a series of montages, meaning danger is almost never present. When Lowery recaps Tucker’s umpteen prison breaks, the countdown unfolds in swift, single-shot summaries—a sequence that recalls the roster of extracurricular activities maintained by Max Fischer in Rushmore (1998). Cinematographer Joe Anderson shoots on 16mm stock to capture an at once earthy, gritty, and muted color image, accented only by vintage-looking title cards about the supposed veracity of Tucker’s story. Anderson’s long zooms and evident grain, though capturing a long-gone era of filmmaking, also draw attention to themselves in unpleasant ways—Lowery’s insistence on old-fashioned forms calls attention to itself, drawing the viewer away from the already laid-back narrative thrust. A similar quality in his last release, A Ghost Story (2017), prevented this critic from being completely immersed.

Fortunately, the performances throughout prevent Lowery’s overly self-conscious technique from distracting the viewer beyond recovery. Redford, as one might expect, uses every inch of weathered face, from his alert eyes to his humored glances, to imbue Tucker with a pleasantness that overcomes even the character’s uglier truths (revealed in a brief scene with a daughter, played by Elisabeth Moss, whom the bank robber knows nothing about). Waits has a wonderful scene that explains, in a way only Waits can, “and that’s why I hate Christmas.” And Spacek has a benevolent innocence that deepens her character’s affection for Tucker. It’s all very sweet in a way the viewer can easily brush off when it’s over, which isn’t necessarily a good thing. The Old Man & the Gun works because of Redford, his persona a permanent fixture in the minds of moviegoers. And so, perhaps the film is a thank you note to Redford. Lowery’s recent emergence has been tied to the actor, from the writer-director’s breakout at Redford’s very own Sundance Film Festival in 2013 with Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, to Redford’s starring role in the better-than-it-has-any-right-to-be Pete’s Dragon remake (2016). Moreover, everyone who enjoys movies undoubtedly loves one, or doubtlessly more than one, of Redford’s roles. Without this metatextual commentary on the star, The Old Man & the Gun wouldn’t amount to much. With him, it doesn’t have to.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review