The Nutcracker and the Four Realms

By Brian Eggert |

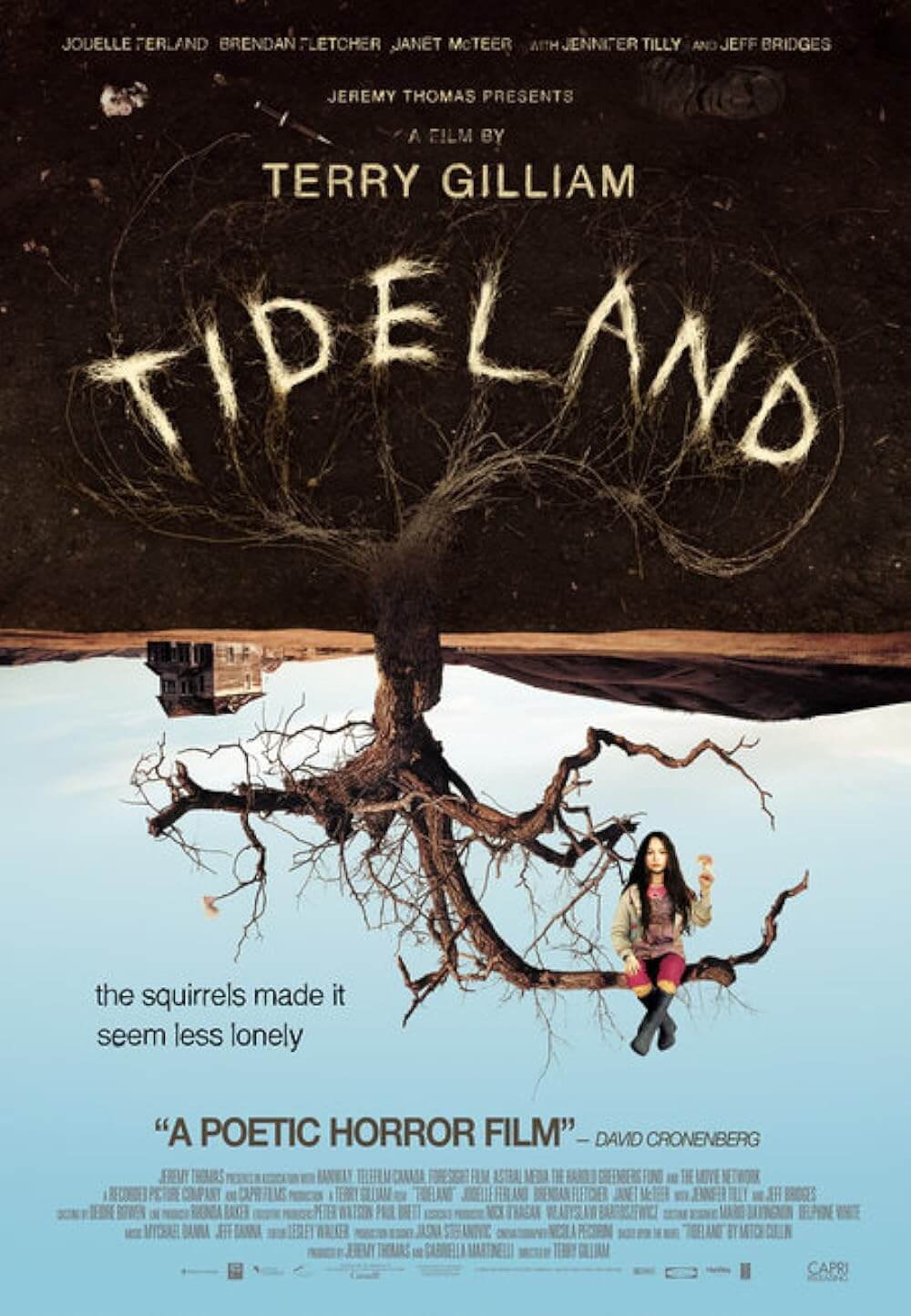

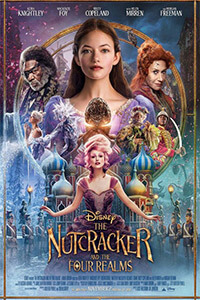

Art direction and production design take precedence over story, performance, music, catharsis, and even dance in Disney’s The Nutcracker and the Four Realms, a vacuous fantasy based, albeit loosely, on the writings of E. T. A. Hoffmann and staging of the famous ballet by Marius Petipa. The expensive production has more in common with earlier Disney releases, namely Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland (2010), or the mega-studio’s various other tales of princesses, than any nineteenth-century source. The movie takes place in a world of elaborate CGI, opening with a tour of London on Christmas Eve as guided by a badly animated owl, before descending into a magical world of imagination. It’s a familiar tale of an emotionally confused young woman who loses herself in a fairy-tale land; and only upon learning that her problems can be solved not through an enchanted key or any other such MacGuffin, but rather by trusting herself, can she defeat evil and return home. Regardless of its conventional story, it’s also a 99-minute mess of stilted dialogue, wooden performances, and predictable themes.

But oh, what a visual experience, as directed by Lasse Hallström (The Cider House Rules), strangely sharing credit with Joe Johnston (Captain America: The First Avenger), who aided Hallström in reshoots by filming some of the more action-packed scenes near the climax. Cinematographer Linus Sandgren (La La Land) presents lush colors and textures—at least, when things exist in the realm of the tangible. Costumer Jenny Beavan (Christopher Robin) conceives of elaborate gowns and memorable outfits, while production designer Guy Hendrix Dyas (Inception) makes everything look like a postmodern storybook—not quite classical, but not quite immersive or edgy either. Unfortunately, the tactile work of these artisans has been glossed over with computer animation, despite Disney’s persistent notion that this, and their recent string of titles ranging from Maleficent (2014) to Beauty and the Beast (2017), occupy a so-called live-action status. If there’s a highlight to the picture, it’s the all-too-brief sequences of ballet that clearly had Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Tales of Hoffman (1951) on the filmmakers’ minds, even if they pale in comparison.

Written by Ashleigh Powell, the story involves a broken, well-to-do British family at the turn of the last century. Clara (Mackenzie Foy) has recently lost her mother, and her melancholy father (Matthew MacFadyen) has the sad duty of delivering his late wife’s final gifts to their children on Christmas Eve. Clara, ever curious, lost in her imagination, and interested in wind-up machines, receives a locked music box in the shape of a metal egg, which she cannot open unless she finds the key. To do so, she must follow her mother’s unambiguous clues (“Everything you need is inside” yourself). That evening, their family attends the annual holiday party hosted by the mischievous Drosselmeyer (Morgan Freeman)—an eye-patched man whose playful grin never explains why or how Clara suddenly finds herself transported to another world. Somehow created by her mother, the titular four realms view Clara as the ruling queen in the absence of her mother.

As it turns out, Clara’s mother somehow imagined into existence a fantasy world of warring states and mistrust. Three seemingly cheery realms stand in conflict with the fourth, as Clara learns from the cotton-candy-haired Sugar Plum (the top-billed Keira Knightley), dictator over the Land of Sweets; Shiver (Richard E. Grant), ruler of the Land of Snowflakes; and Hawthorne (Eugenio Derbez), who runs the Land of Flowers. To recover the mysterious key to her music box, Clara teams with a loyal nutcracker soldier, Phillip (Jayden Fowora-Knight), to enter the shrouded and supposedly dangerous Fourth Realm, a creepy circus world headed by Mother Ginger (Helen Mirren) and the Mouse King (a personified collection of CGI mice). But frankly, each of the realms is unintentionally eerie. The entire land is filled with unsettling masks, warped sculptures, and gear-based mechanisms from yesteryear, recalling a prolonged experience in Alex Jordan Jr.’s kitschy, nightmarish The House on the Rock. Just try to not have night terrors after witnessing a scene with a living nesting doll more terrifying than Twisty the Clown from American Horror Story. It’s not quite as menacing as Return to Oz (1985), which opened with Dorothy receiving electro-shock therapy, but bad dreams will be had.

As it turns out, Clara’s mother somehow imagined into existence a fantasy world of warring states and mistrust. Three seemingly cheery realms stand in conflict with the fourth, as Clara learns from the cotton-candy-haired Sugar Plum (the top-billed Keira Knightley), dictator over the Land of Sweets; Shiver (Richard E. Grant), ruler of the Land of Snowflakes; and Hawthorne (Eugenio Derbez), who runs the Land of Flowers. To recover the mysterious key to her music box, Clara teams with a loyal nutcracker soldier, Phillip (Jayden Fowora-Knight), to enter the shrouded and supposedly dangerous Fourth Realm, a creepy circus world headed by Mother Ginger (Helen Mirren) and the Mouse King (a personified collection of CGI mice). But frankly, each of the realms is unintentionally eerie. The entire land is filled with unsettling masks, warped sculptures, and gear-based mechanisms from yesteryear, recalling a prolonged experience in Alex Jordan Jr.’s kitschy, nightmarish The House on the Rock. Just try to not have night terrors after witnessing a scene with a living nesting doll more terrifying than Twisty the Clown from American Horror Story. It’s not quite as menacing as Return to Oz (1985), which opened with Dorothy receiving electro-shock therapy, but bad dreams will be had.

Most frightening of all is Sugar Plum who, in addition to her baby-voice, provides a Trumpian character bent on dividing and conquering the land to satiate her ambition. Powell’s script saddles Knightley with Bond villain dialogue like “Destroy him!” and “You just had to interfere, didn’t you?”—or pun-laden lines such as “I’m just so pleased you decided to drop in” before dropping someone. But the lesson here is clear: leaders are dangerous when they do what’s best for themselves, not their people. Political texts aside, Knightley’s commitment to her over-the-top character almost distracts from how badly it’s written. Elsewhere in the cast, the Los Angeles-born Foy adopts a convincing British accent, but her presence is charmless. Having given accomplished turns in The Conjuring and Interstellar, the 17-year-old demonstrates that she may not be suited for green-screen work. Then again, there’s hardly a good performance in the cast, regardless of the impressive roster of talents involved. When the script has nothing compelling to say, not even performers like Mirren, Knightley, and Freeman can do much to elevate it. And then the movie ends on a curious undercurrent of incestuousness in a dance between Clara and her father, the same dance shared by the man and his late wife.

More substantial than the aforementioned Alice in Wonderland but still a computer confection, the disappointingly nutless (in its lack of walnuts) The Nutcracker and the Four Realms is preoccupied with set-pieces, eye-candy, and eventually CGI battles, as opposed to engaging its young audience or asking them to consider the complexity of their unformed emotions—as Pixar often does. It was made to sell tickets, and it will probably make a lot of money and entertain a lot of children. But it’s another formulaic Disney movie with few merits beyond the superficial. What’s more painfully obvious is that the filmmakers had a real opportunity to try something alternative to the usual Disney model. Over the end credits is a ballet sequence featuring Misty Copeland, a dancer for the American Ballet Theatre, performing a brief segment of the Nutcracker ballet. And though the scene is poorly edited and doesn’t dwell enough on Copeland for the audience to fully appreciate her form and routine, the brief glimpses of choreography and minimalist staging prove that a minute or two of classical ballet has more artistic value than another scattershot blockbuster.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review