The Northman

By Brian Eggert |

Early in The Northman, a Viking epic from arthouse favorite Robert Eggers, a wise man asks a king and prince to prove they are men. The nobles, crawling on their hands and knees, growling and howling like dogs, respond with a respective belch and fart. In doing so, both prove they’re “wise enough to be the fool.” The scene demonstrates a guiding philosophy in Eggers’ work that values historical reality over audience expectation. The sprawling, panoramic production conveys Viking life with authentic details, telling a vast and gory tale of revenge centered on Alexander Skarsgård, who helped develop the film. Eggers doesn’t shrink from realities that might seem silly, cruel, or divisive today. Much like the singular ambition of its central warrior, The Northman reaches for historical and mythological accuracy, refusing to bend to modern sensibilities to soften the blow of anthropological interest. That artistic choice results in refreshing and brave filmmaking, but it’s also distancing. In a sense, Eggers does not care if the moviegoing public comes away having learned about themselves or achieved some measure of catharsis. The film serves the internal needs of its protagonist, nothing more. The conceit is admirably single-minded.

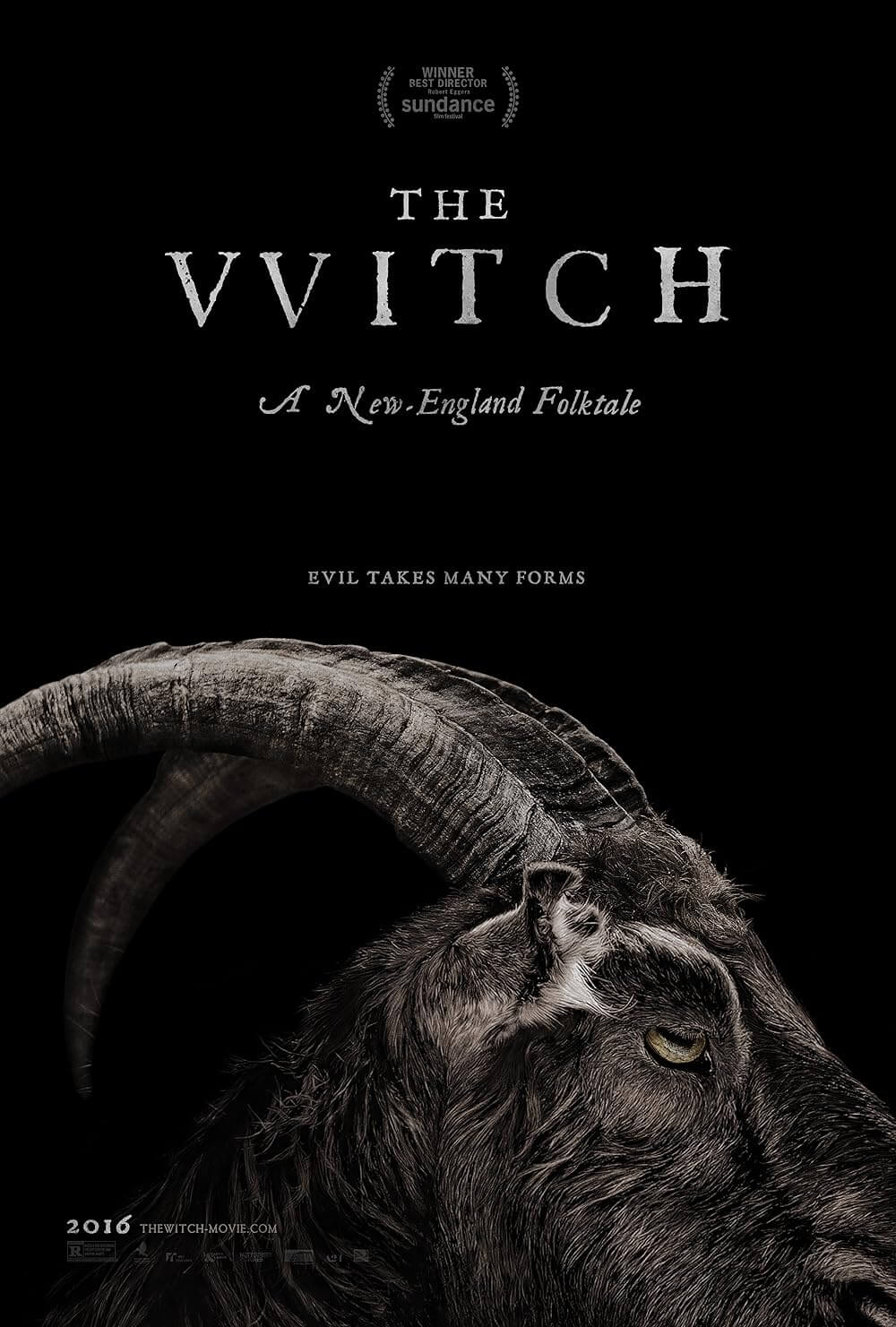

Then again, Eggers combines period-accurate historicity with an otherworldly tendency in each of his three features. His debut The Witch (2015), shot in austere natural light and claustrophobic spaces, and using stripped-down production values, took place in a New England forest and drew much of its dialogue from actual journals written around 1630. However, the haunting elevation in the finale is a pure folk horror movie flourish. His follow-up, The Lighthouse (2019), a film that I have come to love since my original lukewarm review, employed vintage cameras to capture stark black-and-white images, lending the appearance of an old photograph to match the nineteenth-century locale. Yet, Robert Pattinson’s wickie finds himself overcome by nautical folklore, including a mermaid, tentacles, and an old story about the dangers of killing seabirds. Finally, The Northman features an equal helping of mythos embedded into the screenplay by Eggers and his Icelandic co-writer Sjón. Although they sourced Viking historians to ensure the accuracy of their research, including scant archeological evidence compared to other ancient cultures, the writers also infuse rituals, magic, and prophecy into the mix.

Drawing from the same medieval Scandinavian legend that inspired Hamlet, except set around 900 A.D., the story follows Amleth (Skarsgård)—a Viking dead set on hunting down his half-uncle Fjölnir the Brotherless (Claes Bang) to avenge the death of his father, King Aurvandill War-Raven (Ethan Hawke). At ten years old, Amleth (played by Oscar Novak) witnesses Fjölnir take the throne and the widowed Queen Gudrún (Nicole Kidman) for himself. Amleth escapes, his half-uncle believing he died during the violent coup. Years later, the Prince, having pledged himself to vengeance, has spent years transforming himself into an unstoppable behemoth in a band of berserkers, raiding Slavic villages, biting off faces, and burning alive anyone who cannot be sold as a slave. In their latest conquest, Amleth meets a seer (Björk), who sets him back on the path of revenge. He also meets a cunning slave named Olga of the Birch Forest (Anya Taylor-Joy), and together, they’re sold as slaves to Fjölnir, who has resituated in Iceland. Their plan entails terrorizing Fjölnir’s camp from within before Amleth confronts his enemy.

Whereas Eggers’ two arthouse films before this could hardly be called straightforward, they both had a linear trajectory: The Witch moved upward toward the treetops; The Lighthouse spiraled down into Davy Jones’ locker, metaphorically so. Nevertheless, to watch them is to grasp at their oblique and unconventional execution, only to realize the journey Eggers has set into motion by the end. By contrast, The Northman’s narrative linearity pursues a traditional revenge story path, stalking one objective to the next until the fateful conclusion. Amleth must acquire valuable items—such as a mythic sword held by an undead warrior—before he can face the ultimate boss battle. This structure at first seems like a video game but mirrors the narrative order of the monomythic hero, the stuff of Gilgamesh and Odysseus. Eggers tells the story without a smidgen of irony, without a note of heavy metal guitar or Led Zepplin on the soundtrack, which will make audiences accustomed to deflating snark or obvious referencing to antecedents squirm from its seriousness and brutality. Expect uncomfortable laughter throughout from unprepared moviegoers.

Whereas Eggers’ two arthouse films before this could hardly be called straightforward, they both had a linear trajectory: The Witch moved upward toward the treetops; The Lighthouse spiraled down into Davy Jones’ locker, metaphorically so. Nevertheless, to watch them is to grasp at their oblique and unconventional execution, only to realize the journey Eggers has set into motion by the end. By contrast, The Northman’s narrative linearity pursues a traditional revenge story path, stalking one objective to the next until the fateful conclusion. Amleth must acquire valuable items—such as a mythic sword held by an undead warrior—before he can face the ultimate boss battle. This structure at first seems like a video game but mirrors the narrative order of the monomythic hero, the stuff of Gilgamesh and Odysseus. Eggers tells the story without a smidgen of irony, without a note of heavy metal guitar or Led Zepplin on the soundtrack, which will make audiences accustomed to deflating snark or obvious referencing to antecedents squirm from its seriousness and brutality. Expect uncomfortable laughter throughout from unprepared moviegoers.

The lack of irony and meta-ness serves the Viking frame of mind and The Northman’s theme of fate. Within the first 15 minutes, King Aurvandill and his jester-seer (Willen Defoe) reveal Amleth’s fate and declare there will be no escaping it. Eggers never wavers from that bearing, constraining the viewer to Amleth’s mindset and grim morality that place vengeance, an honorable death in battle, and his arrival in Valhalla above all else. A post-modern Viking story might take issue with this morality and find Ameth questioning his origins, but not here. With his fate pulling him relentlessly toward his objective, he barely stops to question his motivations when given new information that should divert him. Amleth has such an obstinate determination for vengeance and death in battle that he might be a dull character if not for his peerless certitude. Moreover, even supernatural forces align with him. Fate operates like a force of Nature here, helping Amleth fulfill his destiny by curbing his actions with a sword that cannot be unsheathed at the wrong time; fate also prevents others from taking action that would upset his journey. Eggers’ willingness to embrace this element removes any chance of Amleth diverting from his quest and speaks to the singular aim of the Viking.

Shooting in Ireland but digitally inserting Icelandic backdrops into the frame, the production looks dreamy, not the entrenched and realist verisimilitude witnessed in Eggers’ earlier films. If The Witch betrayed its naturalism throughout with a final special-effects scene that felt inappropriate next to what came before, The Northman’s use of CGI remains consistent throughout—which is to say, less like one of Eggers’ unflinching aesthetic experiences and somewhere between a Ridley Scott epic and Zack Snyder’s 300 (2007). Still, even though the director reported to Focus Features on a budget ranging from $70-$90 million, he was given the freedom to shoot alongside his regular cinematographer, Jarin Blaschke, in a manner he deemed best. A more conventional Hollywood production might have two or three cameras capturing the action, allowing for multiple options and doubtless overediting. Eggers’ single-camera approach ensures that whatever the studio’s demanded, the director controlled the execution. Thus, The Northman never feels like a compromised vision.

Quite the contrary, the film is remarkably immersive and convincing (even if the English-language dialogue and Scandinavian accents create a rare historical break in the production). Linda Muir’s effective garbs don’t look like ornate fantasy pieces but practical clothing made from the materials of the day. Sound designer Jimmy Boyle creates another rapturous layer with haunting sonic effects that make good use of every speaker in a surround sound system. The Northman is also a shockingly violent story. When Amleth and Olga plan a campaign of fear and terror on Fjölnir’s soldiers, the horrific result speaks to the twisted limits of Amleth’s mind, action, and morality. Above all, Blaschke’s imagery uses the same grandiosity that inspires Amleth—the kind of imagery that exists in the mind of someone who believes in his fateful ascent to Valhalla. Indeed, the whole thing ends with Amleth and Fjölnir battling atop a volcano in the buff, a scene that doesn’t quite challenge similar nude combat in Ken Russell’s Women in Love (1969) or David Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises (2007), but it remains downright intense nevertheless.

Quite the contrary, the film is remarkably immersive and convincing (even if the English-language dialogue and Scandinavian accents create a rare historical break in the production). Linda Muir’s effective garbs don’t look like ornate fantasy pieces but practical clothing made from the materials of the day. Sound designer Jimmy Boyle creates another rapturous layer with haunting sonic effects that make good use of every speaker in a surround sound system. The Northman is also a shockingly violent story. When Amleth and Olga plan a campaign of fear and terror on Fjölnir’s soldiers, the horrific result speaks to the twisted limits of Amleth’s mind, action, and morality. Above all, Blaschke’s imagery uses the same grandiosity that inspires Amleth—the kind of imagery that exists in the mind of someone who believes in his fateful ascent to Valhalla. Indeed, the whole thing ends with Amleth and Fjölnir battling atop a volcano in the buff, a scene that doesn’t quite challenge similar nude combat in Ken Russell’s Women in Love (1969) or David Cronenberg’s Eastern Promises (2007), but it remains downright intense nevertheless.

Eggers’ only misstep lies in his all-star cast, some of whom fail to disappear into their roles. Kidman’s performance feels better suited for a standard Hollywood spectacle, for instance, with showy scenes for the camera. Elsewhere, and this is nitpicky, but consider it the bane of my existence that Alexander Skarsgård will forever be the Goth vampire—named Eric Northman no less—from HBO’s True Blood. He never quite shed that association for me, even in his subsequent and iconic roles as Tarzan or Randall Flagg. Here, Skarsgård looks Olympian, his body sculpted into a warrior’s physique, his massive shoulders pushing his head forward and down. When he first raids alongside the berserkers under a wolfskin, his hair appears long and shaggy, his beard unkempt. Then, Amleth resolves to disguise himself as a slave to get to Fjölnir. When he does, Amleth gives himself a haircut and trims his beard down, and he comes away looking distractingly polished—like he just dropped $150 at a salon. Where did he learn to cut his hair with such expertise? It looks like Eric Northman playing Viking dress-up. In a film where every surface detail has been meticulously researched and doubtlessly verified by scholarly sources, Amleth’s haircut and trimmed beard look curiously hip. But don’t let that bother you as it does me.

On the press tour to promote The Northman, the Swedish-born star has shared memories of growing up around towering rune stones and listening to his grandfather recount Viking legends. When, by chance, he met Eggers in Iceland five years ago, the two talked about making a Viking film. They called it fate. Incidentally, fate is the most compelling aspect of the film. But Amleth is less in a relationship with fate than at its service, robbing him of dimension as a hero. Once the viewer recognizes that Amleth will not leave or escape his current path, the viewer may feel somewhat detached and uninvolved, just watching the inevitable occur as a sort of anthropological case study. Even so, Eggers has constructed a gorgeous, bloody affair whose magical visions of zombie warriors and valkyrie riders and the gates of Valhalla place us inside our hero’s unwavering mindset. It’s a film splattered with blood, mud, and literal guts, but there is also music, dancing, ghosts, and tradition. Eggers deploys each aspect of Viking culture to incredible effect without judgment, and that’s a rare thing in any historical film today.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review