The Nice Guys

By Brian Eggert |

Shane Black’s persistent themes achieve a pitch-perfect harmony in The Nice Guys, a 1970s-set comic thriller with a joyful application of the writer-director’s oft-used mechanisms. Famous for turning actioner conventions on their head, Black has a talent for reclaiming tired formulas and giving them new life. Each of his projects is essentially a buddy film featuring two leads, often male. His odd couple sets out on a mysterious pulp noir case fraught with twists and turns, revealing a powerful crime syndicate at its center. Like a hard-boiled novel, two separate cases end up being connected, as if Raymond Chandler and Thomas Pynchon conceived their intricacies themselves. Black’s films usually take place in Los Angeles, mostly around Christmas, and through the course of the story, at least one debauched L.A. party is attended—resulting in a slight, if also celebratory, criticism of Hollywood excesses. Wherever the story takes its audiences, there’s plenty of humor along the way, even if the proceedings end in bullets. The Nice Guys follows this familiar Shane Black trajectory to the letter, but never has the filmmaker’s brand of storytelling felt so singularly accomplished.

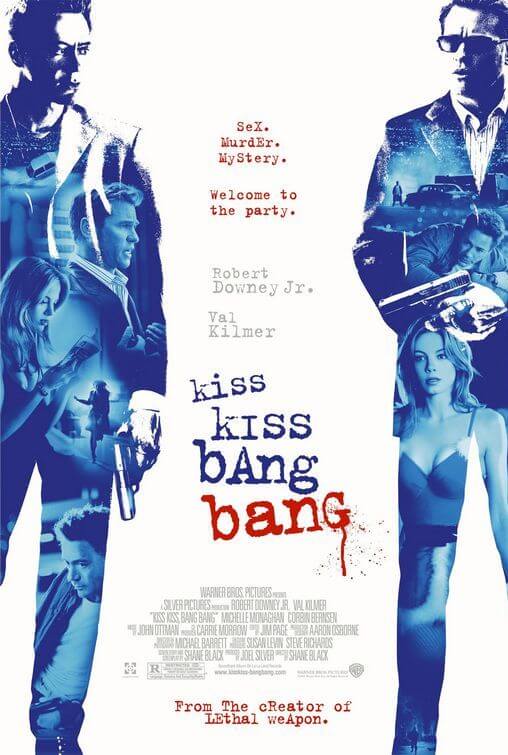

Black’s third film as director has been a long time coming; it feels like a culmination. After serving as the high-paid Hollywood screenwriter of Lethal Weapon (1987) and The Last Boy Scout (1991), the hard-partying Black was all but ejected from the industry after The Long Kiss Goodnight bombed in 1996. He eventually made a modest return in 2005 with Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, a meta-infused noir starring then-ousted actors Robert Downey Jr. and Val Kilmer. That underseen, now cultish L.A. noir made up for its low-budget with its frisky strain of self-awareness dialed up to eleven. Black’s efforts resulted in Downey receiving a lot of attention and, despite the film disappearing from theaters, it helped Downey land the Iron Man role and rise to superstar status. Once Downey had achieved new heights under Marvel, the actor remembered Black, the writer-director who took a chance on an actor then defined by drug-addiction and very public arrests. Black’s second film as writer-director was Iron Man 3, which was less a typical Marvel product than a film shaped by the aforementioned Black-isms.

Indeed, Iron Man 3 comes complete with a hero who’s barely in costume and destroys his inventory of armored suits; it even comes up with a witty solution to its seemingly central villain—a solution that picks apart Hollywood as only Shane Black does. Although die-hard comic fans balked at Black’s freeform treatment of Marvel characters in Iron Man 3, the film proved hugely successful, and demonstrated that Black could deliver on larger budgets. Now with some hard-earned freedom, Black proceeded on The Nice Guys—a $50 million film that is neither a low-budget comeback nor a studio project with something to prove. It’s more like Black’s earlier work as a screenwriter, in that it’s an action comedy, but it’s also shaped by Black’s fascination with pulp novels, just as Kiss Kiss Bang Bang is. However, dissimilar from his directorial debut, The Nice Guys resists a modern sense of onscreen self-awareness; there’s no breaking of the Fourth Wall, no stopping the film stock to comment on the plot or narration, and the characters aren’t glaringly aware of their own presence in a Hollywood film.

If Kiss Kiss Bang Bang was dialed up to eleven (to a fault) through its show-stopping meta humor, The Nice Guys achieves a modulated ten by setting aside any Fourth Wall toppling. The film contains solid, well-rounded storytelling and seems like a combination of L.A. Confidential (1997) and Inherent Vice (2014). Set in Los Angeles in the year 1977, the film revels in the scenery with billboards from the era (Airport ’77, Jaws 2, Smoky and the Bandit, etc.), as well as comedy club marquees advertising the breakout stand-up comics at the time (Richard Lewis, Tim Allen, Richard Belzer). These details, as well as the fictional posters for cornball pornography, which wasn’t an anonymous in-home enterprise on the internet at the time, but rather a peculiarly shared theatrical experience, delight us. At the center of the film, though he never appears alive, resides a porno producer who’s somehow involved in the disappearance of Amelia (Margaret Qualley), a young would-be porn actress whose mother (Kim Basinger) is looking for her.

But this says nothing of our odd couple heroes, played by actors who employ every ounce of charm in their not-inconsiderable arsenal to make their deeply flawed, crackerjack characters lovable. Russell Crowe plays Jackson Healy, a round muscle-for-hire who accepts cash to rough up anyone who’s got it coming. Healy lives a substance-free lifestyle in an apartment above The Comedy Store in West Hollywood, and he would probably beat up your grandmother if you paid enough. Amelia hires Healy to punch out Holland March (Ryan Gosling), a hard-drinking amoral P.I. shadowing her for seemingly unconnected reasons. After realizing they can help each other, Healy and March form a temporary alliance to find Amelia—tracking her down to an elaborate party thrown by same porno producer, where they must evade shady goons played by Keith David and Beau Knapp. The worst of them is John Boy (Matt Bomer), a methodical hitman flown in from Detroit (whose name coincides with a character from The Waltons, a show much-discussed in the period-specific dialogue).

Crowe and Gosling play off one another with flawless comic timing and chemistry. Of course, many of the quips and punchy dialogue should be attributed to Black, who all but invented the action-comedy with Lethal Weapon. But the actors are clearly having a blast in their roles and improvise on the material. Healy could be called the straight man, although his tough comebacks often deserve a laugh. But it’s March who steals the show. Gosling’s character is irresponsible and at times pathetic, all but losing control after a few drinks and not opposed to screaming like a banshee in pain. Whether his character is stumbling over his words in a riotous scene in which he drunkenly questions a couple of actresses, or he’s hallucinating a giant smoking bumblebee, Gosling devotes himself to the moment like few others could. He puts the same amount of intensity in comedy as he does in his dramatic roles like in Drive (2011) or The Place Beyond the Pines (2013), making his approach to a comic performance as effortless-looking-but-labored-over as his dramatic work.

Beneath the humor and thrills, Black’s scenario gives way to moments of considerable subtext, informed by historical ironies and some effective character depth. “Mark my words,” says March near the conclusion, “in five years we’ll all be driving electric cars from Japan.” Without spoiling too much, the plot involves an elaborate conspiracy to keep the automotive industry running, regardless of the damage the manufacturers knowingly cause to the environment. There’s a sense that a decision was made here to keep making money, even if it destroys the atmosphere; and while the theme is handled with humor (Black pokes fun of a group of protesters acting on behalf of birds everywhere), it also enhances the film overall. Elsewhere, Healy follows the same course as Crowe’s character Bud Fox in L.A. Confidential—a brute who finds he desperately needs to do something good. March goes through most of the film drunk, while his 13-year-old daughter Holly (Angourie Rice) bemoans her irresponsible father for drinking too much following the death of her mother and his late wife. Another Black-ism: a plucky youngster tossed into the otherwise adult events. Rice, whose bright character involves herself in almost every aspect of the film’s investigation, is bound to become a star based on her excellent performance here. (Ty Simpkins, who starred as Black’s plucky youngster in Iron Man 3, also appears in the opening scene.)

Beneath the humor and thrills, Black’s scenario gives way to moments of considerable subtext, informed by historical ironies and some effective character depth. “Mark my words,” says March near the conclusion, “in five years we’ll all be driving electric cars from Japan.” Without spoiling too much, the plot involves an elaborate conspiracy to keep the automotive industry running, regardless of the damage the manufacturers knowingly cause to the environment. There’s a sense that a decision was made here to keep making money, even if it destroys the atmosphere; and while the theme is handled with humor (Black pokes fun of a group of protesters acting on behalf of birds everywhere), it also enhances the film overall. Elsewhere, Healy follows the same course as Crowe’s character Bud Fox in L.A. Confidential—a brute who finds he desperately needs to do something good. March goes through most of the film drunk, while his 13-year-old daughter Holly (Angourie Rice) bemoans her irresponsible father for drinking too much following the death of her mother and his late wife. Another Black-ism: a plucky youngster tossed into the otherwise adult events. Rice, whose bright character involves herself in almost every aspect of the film’s investigation, is bound to become a star based on her excellent performance here. (Ty Simpkins, who starred as Black’s plucky youngster in Iron Man 3, also appears in the opening scene.)

Black’s production looks sharp, decked-out with ‘70s costumes and styles, an excellent soundtrack supervised by Randall Poster, and washed-out colors courtesy of Philippe Rousselot’s cinematography. Despite violence, swearing, sexuality, and generally sordid goings-on through the two-hour film, the overall tone remains lighthearted—perhaps because Healy and March carry on through a series of moronic errors, somehow managing to survive. Or perhaps because the script by Black and Anthony Bagarozzi doesn’t take itself too serious, even when it’s making a point about the corrupt automotive industry souring the atmosphere. There’s also a strain of pure silliness in The Nice Guys. March declares at one point, “I think I’m invincible.” He may just be after surviving several shootouts, falling off two balconies, a couple car wrecks, several nasty wounds, and a broken wrist. Because the film is shot in a rather straightforward ‘70s style, we’re not expecting its surreal moments or the comical treatment of action sequences, a quality Black fully exploits to hilarious effect.

The Nice Guys is a jubilant, gritty, and guilt-free lark. As a critic, it’s so satisfying to see a film that serves as both strong filmmaking and popcorn-munching entertainment. Although, I must admit, my partiality to Shane Black’s style, sometimes morbid sense of humor, and embrace of recurrent writerly tropes may leave me biased, insomuch as any critic is biased, consciously or not, by their personal tastes. My wife and I noted after our screening how much of the audience wasn’t laughing when they should have been. In several moments of intended humor, we were the only two people laughing in a half-full theater during a Thursday preview. Afterward, we each walked out overjoyed by the experience, whereas our fellow moviegoers seemed indifferent. Consider that a warning, I guess. What I hope is you see Shane Black’s film as I did, informed of how the writer-director’s past and previous output personally shaped the material. This is an extremely accomplished, fully envisioned, and wholly satisfying action-comedy—something far too rare in the film industry today.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

As the season turns toward gratitude, I’m reminded how fortunate I am to have readers who return week after week to engage with Deep Focus Review’s independent film criticism. When in-depth writing about cinema grows rarer each year, your time and attention mean more than ever.

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your moviegoing—whether it’s context, insight, or simply a deeper appreciation of the art form—I invite you to consider supporting it. Your contributions help sustain the reviews and essays you read here, and they keep this space independent.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review