The Naked City

By Brian Eggert |

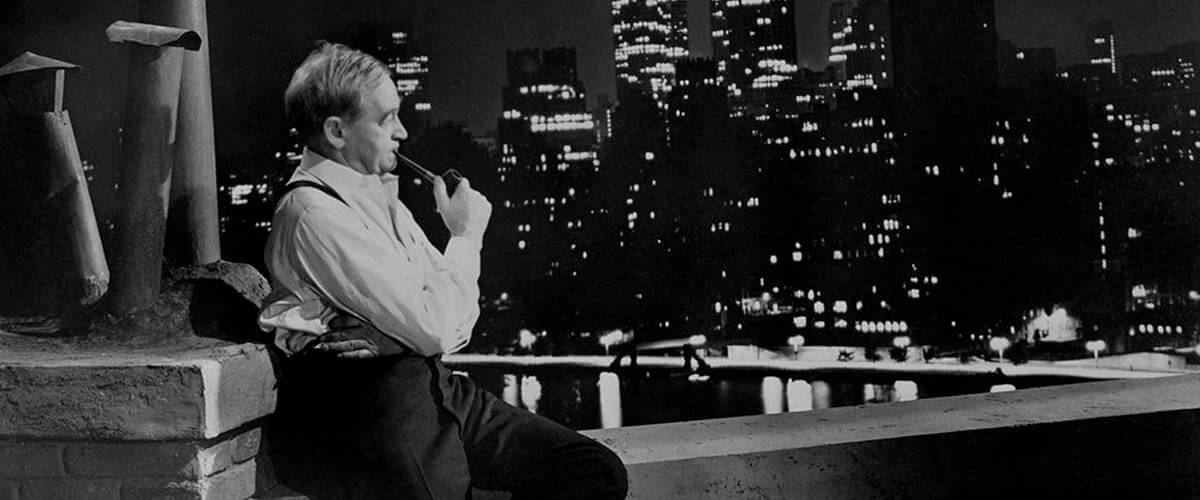

Though this film noir follows two detectives unraveling a murder case, The Naked City’s main character is, to coin a term from another noir picture, the asphalt jungle. Director Jules Dassin shot the picture on location in New York City without the benefit of studio lots or soundstages. The film’s style ignores the typical expressiveness of noir characters and replaces them with somewhat prosaic yet acceptably charming detective characters. Where they go and the people they meet are only the conduits through which we become familiar with the urban landscape. The characters themselves help to humanize the film’s apathetic nucleus: the city.

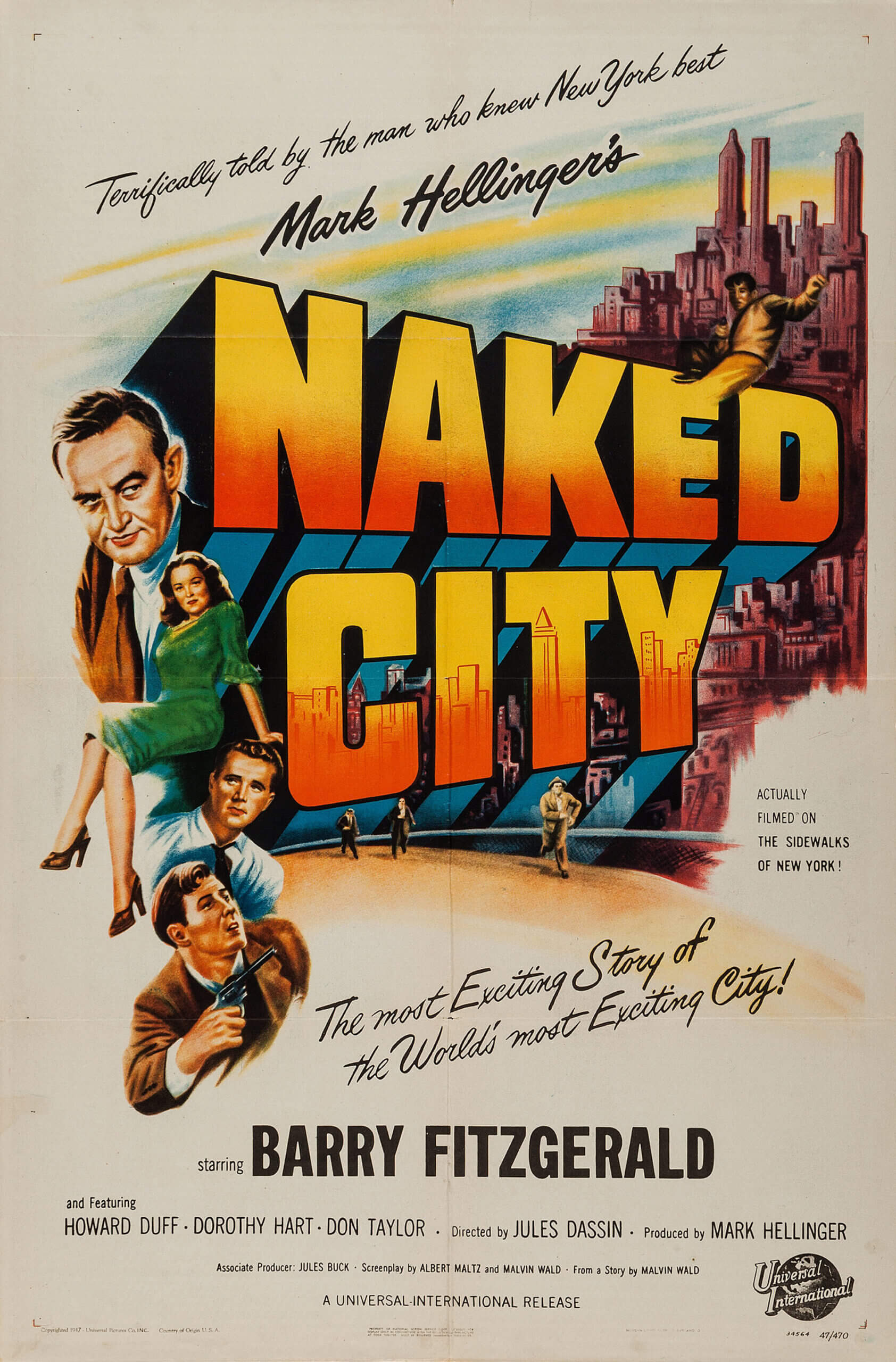

The film was inspired by a book called Naked City created by independent photographer Arthur Fellig, more commonly known as Weegee. The 1945 book was a collection of photos that showed the true-crime side of the city. An unflinching look at the underbelly of urbanity, Weegee’s book caught the eye of film producer and former newspaper man, Mark Hellinger. After seeing the book, Hellinger began work on producing a filmic text in which the city is the main character.

The Naked City begins with narration by Hellinger (who also produced one of the first film noirs, 1946’s The Killers), in a style reminiscent of 1940s newsreels or even like a benshi narrator to a Japanese silent film. During Japan’s silent film era, a benshi would stand next to the screen and provide voices for characters, explain plot points, and create sound effects for a silent movie. Hellinger speaks directly to the audience and often provides the same services a benshi might. He describes the layout of the metropolis: how its bare, concrete walls coupled with the documentary style in which the film is shot, create a massive character in the cityscape and the people in it. He shows the everyday lives of New Yorkers. And then, all at once, he shows us the murder of model Jean Dexter.

Hellinger’s presence as narrator reminds us that we’re watching a movie. This might take us out of the picture and make the murder and the subsequent investigation less intriguing, but Hellinger’s voice itself becomes a main character. With his voice, he explains what normally a scriptwriter would use characters and settings to describe, so in turn he becomes part of the plot. It’s an odd choice for a film but one familiar to audiences that, at the time, were watching travelogues in the cinema before the feature. Hellinger is our guide through the city. He introduces us to the film’s main characters, Det. Lt. Dan Muldoon (Barry Fitzgerald) and Det. Jimmy Halloran (Don Taylor); tells us where they’re going and what clues they’re investigating. He is the voice of the motion picture.

Hellinger comes from the era when a producer could have major control over a picture, creatively or otherwise. David O. Selznick, Hal B. Wallis, and others like them, all tightened their grasps around unsuspecting directors (particularly Selznick). Today, most people can’t tell you what a producer does. I can’t help but think of that scene from David Mamet’s film State and Main where a screenwriter asks a member of a film crew what an associate producer credit is, and the crewmember responds, “It’s what you give your secretary instead of a raise.”

The Naked City is structured like the adept child of a documentary and a film noir. William H. Daniels, who shot the legendarily butchered Erich von Stroheim film Greed (1924), shot this picture by showing us only reality. Employing traits of Italian neorealist cinema, most of the shots are exterior ones, and many of the New York monuments are not present. Neorealism often spent its time in unknown neighborhoods; when neorealist director Vittorio de Sica shot Umberto D. in Rome, he didn’t shoot the Colosseum or the Pantheon. In The Naked City, the Brooklyn Bridge, Statue of Liberty, and Empire State Building are never showcased as monuments. The film spends its time in small neighborhoods, retail shops, and on the street, just as Weegee’s book does.

Hellinger’s influence on this picture almost outweighs the director’s presence, but Jules Dassin is such an incredible filmmaker that he can’t be snubbed out—not even by the most powerful producer. Even though Hellinger insisted that the documentary stylization reflects Weegee’s book, Dassin manages a suspenseful finish to the murder mystery with a chase that ends high up among the metal beams of a bridge. We get a glimpse of the cityscape from up there, which, in perspective, illustrates the inconsequentiality of the murderer. When the film ends, of course, the murderer is dead. Hellinger’s narration closes the film with the iconic line, “There are eight million stories in the Naked City. This has been one of them.” That line became popular enough to sustain a television program called The Naked City from 1958-1963; each episode would end with the same message.

One interesting story becomes insignificant when compared to the scope of the city. The city itself is the most interesting character in this film; as cities often have personalities, New York is frequently credited as being the most significant. The Naked City marks the first filmic attempt to describe such a setting as if it were a living being—as close as one can do that without anthropomorphizing it. Writers such as Baudelaire and Louis Aragon gave Paris a similar treatment. The city demands both love and hate; it reveals all the beauty and terror that humanity is capable of within a few hundred square miles.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review