Reader's Choice

The Mystery of the Wax Museum

By Brian Eggert |

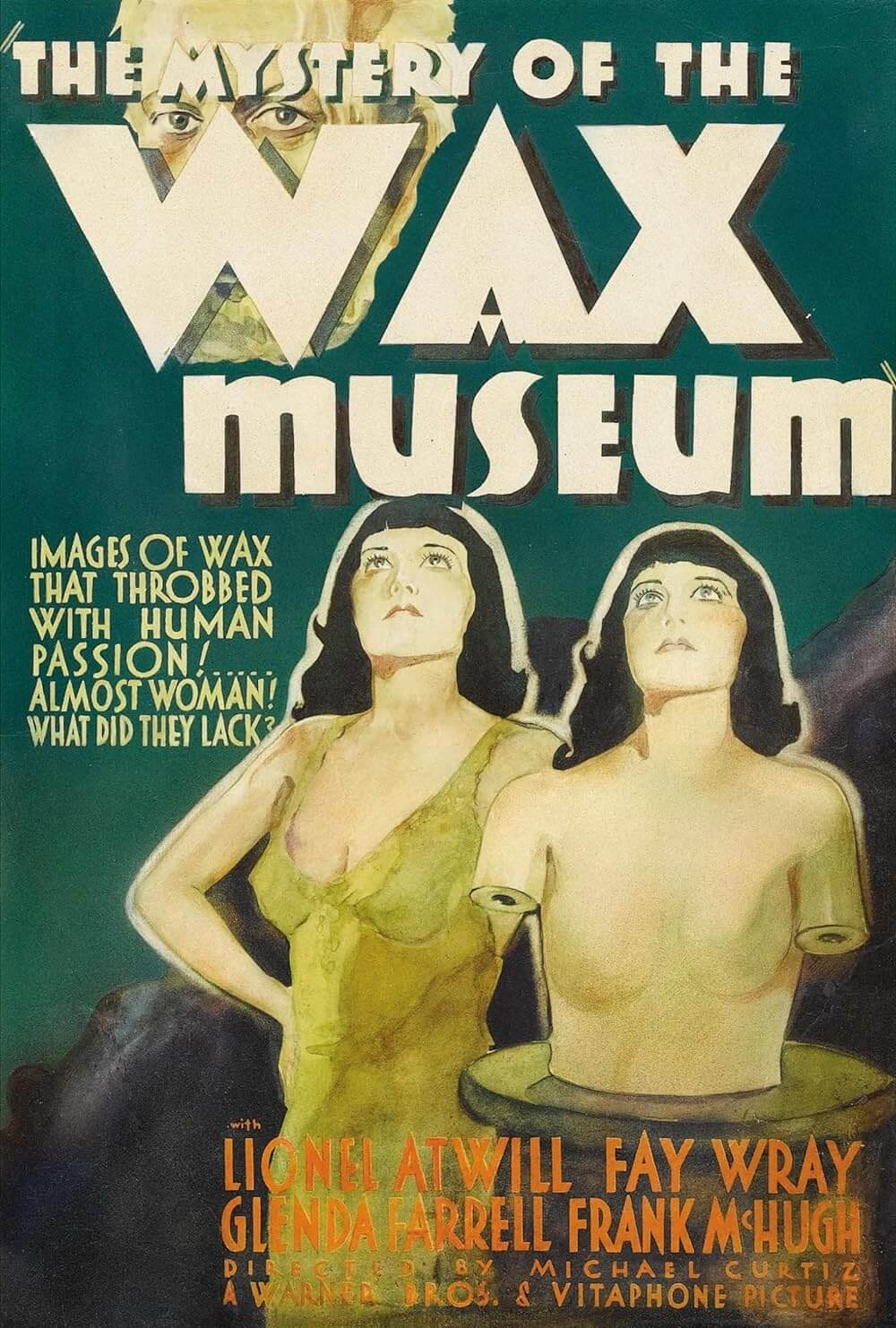

Recently restored to glorious effect, The Mystery of the Wax Museum belongs to a rare breed of horror from the early 1930s that tested the boundaries of representation. During these early decades of the motion-picture industry, studios quickly learned that sex and violence sells. The edgier and more tantalizing the material, the higher the box-office receipts. Although the so-called Golden Age of Hollywood would self-regulate by installing the Production Code in 1934, the brief Pre-Code era supplies rare treasures that question how we might think of classical cinema as safe and moralizing. Released in 1933, The Mystery of the Wax Museum features bootlegging and heroin addiction, corpse robbery and bizarre murders, repulsive faces and disturbing sights that haunt the brain. It’s all the more powerful because of the early form of Technicolor that was used to capture these images in an era where black-and-white photography was the standard. However shocking the film may have been at the time, it has grown not only as a cult object to be cherished by genre aficionados, but as a work that improves with the addition of contexts that underscore its distinct place in film history.

A prologue in London introduces Ivan Igor (pronounced eye-gore), played by Lionel Atwill. He operates a small wax sculpture museum similar to Madame Tussauds, though he single-handedly produces his creations, which he loves more than people, more even than himself—his lifelike statue of Marie Antoinette (a motionless Fay Wray) above all. But his shady partner, Joe Worth (Edwin Maxwell), is losing money and resolves to burn the museum to the ground for the insurance payout. Despite the artist’s attempts to stop his partner, all of Igor’s beautiful creations go up in flames, their melting faces liquifying like the Nazis in Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). Then the film transitions to contemporary New York on New Year’s Day of 1933, where The New York Express reporter Florence Dempsey (Glenda Farrell) investigates the alleged murder of a socialite by the dopey, silver-spooned George Winton (Gavin Gordon). Florence doesn’t buy that George is guilty, in part because the victim’s body has been removed from the morgue—and only the viewer sees the culprit, a phantom-like figure whose grotesque face must be some kind of mask.

Though at the time women were often reduced to damsels and other secondary roles in horror, the trope of the no-nonsense female reporter drove an entire subgenre. For instance, after The Mystery of the Wax Museum, Farrell appeared in a series of Torchy Blane pictures, playing the fast-talking reporter in titles like Smart Blonde (1937) and Torchy Gets Her Man (1938)—Torchy’s popularity even helped inspire Rosalind Russell’s character in His Girl Friday (1940). Here, her comic relief antics often have fun with Pre-Code material, such as a scene where Florence asks a stereotypical Irish cop, “How’s your sex life?” before the frame settles on the officer’s reading material, a magazine called “Naughty Pictures.” Farrell’s wisecracking and plucky Florence also supplies an underdeveloped romantic subplot opposite her editor (Frank McHugh). In any case, The Mystery of the Wax Museum is a rare example of a female-led horror picture, despite the fact that Florence doesn’t save the day. That task is left to Igor’s bland assistant, Ralph (Allen Vincent), who’s engaged to Florence’s roommate, Charlotte (Fay Wray), the spitting image of Igor’s melted Marie Antoinette statue.

Though at the time women were often reduced to damsels and other secondary roles in horror, the trope of the no-nonsense female reporter drove an entire subgenre. For instance, after The Mystery of the Wax Museum, Farrell appeared in a series of Torchy Blane pictures, playing the fast-talking reporter in titles like Smart Blonde (1937) and Torchy Gets Her Man (1938)—Torchy’s popularity even helped inspire Rosalind Russell’s character in His Girl Friday (1940). Here, her comic relief antics often have fun with Pre-Code material, such as a scene where Florence asks a stereotypical Irish cop, “How’s your sex life?” before the frame settles on the officer’s reading material, a magazine called “Naughty Pictures.” Farrell’s wisecracking and plucky Florence also supplies an underdeveloped romantic subplot opposite her editor (Frank McHugh). In any case, The Mystery of the Wax Museum is a rare example of a female-led horror picture, despite the fact that Florence doesn’t save the day. That task is left to Igor’s bland assistant, Ralph (Allen Vincent), who’s engaged to Florence’s roommate, Charlotte (Fay Wray), the spitting image of Igor’s melted Marie Antoinette statue.

Florence’s sleuthing leads her to the newly established waxworks run by Igor, where her gum-chewing instincts tell her there’s something off. The old man’s hands were burned beyond use in the opening scene’s fire, but he uses assistants to complete his creations. Or so he says. As the story unfolds, the odd blend of tones—from the eerie scenes inside Igor’s lab to those following the grotesque-faced phantom to the humorous asides with Florence—recall the mixture of comedy and terror found in so many James Whale pictures from the era. The Old Dark House (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), and The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) each boast Whale’s pre-camp style, some of which is seen in The Mystery of the Wax Museum. Warner Bros. staple Michael Curtiz directed this film, imbuing the material with his signature artistry and commitment to visual clarity. The prolific director of The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and Casablanca (1941), Curtiz rarely receives credit as an auteur given his adaptability to the given material. For instance, The Mystery of the Wax Museum was just one of eight films he directed in 1933. Still, his atmospheric setups, with backgrounds illuminated by creepy green and red lights, give the modern viewer the sense that your local haunted house has come to life.

Much about this film shouts its Pre-Code sensibilities from the mountaintops. Wray appears in scanty clothing in an early scene, and one of Igor’s sculptures features a bloody image of a knife plunged into its chest. Or note the desperate drug addict, played by Arthur Edmund Carewe, who will do anything to score his next heroin fix. Igor, Joe Worth, and the police department each exploit the addict’s desperate need to their advantage. But the film is never more confronting than the final sequence in Igor’s lab, where it’s revealed that he has both stolen corpses from the morgue and killed his enemies to make his wax creations. Using a process involving heated liquid wax, he has replaced their flesh and produced lifelike statues of the dead. But the most shocking revelation had yet to come: When he approaches Charlotte to recreate his Marie Antoinette, she strikes him, breaking the face of an old man mask to reveal the reality of the grotesque phantom underneath. Alas, the film resolves itself with a silly battle between Igor and Ralph (obviously two stuntmen), followed by the unexpected romantic coupling between Florence and her editor. But the film nonetheless sustains the effect of its climactic shock well after the end credits.

The Mystery of the Wax Museum was developed at Warner Bros. as a project to repeat the success of their summer 1932 release, Doctor X. Another Pre-Code horror picture, the predecessor has an almost identical scenario. There’s a killer shrouded in “synthetic flesh” who is responsible for several bizarre murders, and another Atwill character with macabre interests—here, it’s cannibalism. The killer targets a damsel in distress, also played by Fay Wray, and another resourceful young reporter (Lee Tracy, hammy as can be) uncovers the scheme to help the New York authorities. To capitalize on the profitable Doctor X, Warner Bros. purchased the copyright to Charles Belden’s similarly themed short story “The Waxworks” for a mere $1,000—though the story was still unpublished, Belden had written the same basic plotline into a stage play. Screenwriter Don Mullaly was hired to write the script, and Carl Erickson supplied a revision, followed by several more drafts collaborated upon by the two writers. Most of the cast and crew on The Mystery of the Wax Museum were the same as Doctor X as well, including Curtiz as director, Darryl F. Zanuck and Hal B. Wallis as producers, and Leo F. Forbstein as the composer. The new additions to the cast, such as Farrell, were selected from the studio’s stock of contracted players.

Since Doctor X was filmed using the new two-strip Technicolor process developed by Herbert Kalmus’ company, The Mystery of the Wax Museum would be too. As part of Warners’ 1929 contract with Technicolor, the company sent over the same cinematographer, Ray Rennahan, along with camera operator Dick Towers, to oversee its application. Though the two-strip process was incapable of representing the full range of color achieved by the later three-strip process, developed in 1934, it could still convey a great deal in its limited reds and greens—which is especially evident in the recent restoration. The color range gives the picture its Gothic, occasionally putrid look, which lends itself quite well to the horror genre. But the appearance might be confused for hyper-stylization or even faux colorization, as opposed to the innate limitations of the two-strip technique. Still, the presence of deep red blood and luminous orange fire in a 1933 film has a way of sharpening its effect on the viewer—today even more so than the year of its release, since the film was often projected in black-and-white due to ill-equipped moviehouses. Technicolor, and the intense lights used to enhance the process, resulted in another haunting quality. Since real wax sculptures would melt under the harsh lighting conditions, Curtiz used a combination of mannequins and actors to play statues. Though the resulting effect means the occasional gaffe, such as a statue that blinks now and then, it also lends the picture the disturbing sense that these figures are alive—that Igor has somehow imbued them with terrible life.

The rushed production started in September of 1933 on a budget of $230,000, and it wrapped a month later. Anton Grot, the Polish art director who oversaw dozens of the Warners’ productions, conceived the film’s elaborate and striking sets—some of them repurposed from the set of Doctor X—in a combination of expressionist and Art Deco styles. Grot and Curtiz worked together to fill the frame with shadows and bold colors, oddly angled spaces, and a rich depth of field. In promotional material from the period, Grot described the approach as full of “impending calamity, of overwhelming danger.” Within Grot’s sets, Curtiz creates unforgettable images, such as his regular use of tall shadows dwarfing the characters in the frame—a directorial signature. None of it looks overly stylized, however. Curtiz notes in the film’s press materials that he specifically resisted the temptation to use “unusual camera angles,” which call attention to themselves and numb the viewer to their effect. Instead, he uses them only in a few distinct scenes—such as a brief moment in the morgue, or later in Igor’s laboratory for a low angle just before the climactic reveal.

All of this artistry was overlooked by critics at the time, who frequently attacked The Mystery of the Wax Museum from a moral perspective or simply dismissed it as lowbrow fare. In his New York Times review, Mordaunt Hall accused “this unhealthy film” of “going too far,” while the Variety critic dismissed it as “one of those artificial things” like Dracula (1931) or Frankenstein (1931). Other critics took the “mystery” of the title too literally and complained about the film’s lack of an adequate detective story. The critic in Time magazine noted how the film “breaks the rule that everything [in a mystery] must be explained in the finish.” The critic in the Los Angeles Times claimed, “It’s not a critic’s picture, nor one that invites lengthy analysis.” Despite this general panning, the film performed exceedingly well at the Depression-era box-office, where people needed to find something scarier than bread lines and overdue bills. It was Warners’ fourth-highest performer of 1933, earning $1.1 million.

It’s not surprising that critics at the time misunderstood The Mystery of the Wax Museum. Horror was still a relatively young genre, its boundaries still being explored and tested on the screen. Doubtless, critics expected another creature feature like so many Universal Pictures releases, not something that mixes genres in the same way as modern horror-comedies—with genuine scares and laugh-out-loud humor. Although it bears a dramatic structure that is both predictable and occasionally uneven, especially as the story transitions from the plucky newsroom to Igor’s nightmarish laboratory, its disparate elements prove endearing. The horror works on its own, just as Farrell’s comic asides produce genuine charm. Its cohesiveness may be wobbly, but its ability to keep the audience feeling off-kilter and frequently jarred remains undeniable. Newly restored by the UCLA Film Archive and Film Foundation from a print in Jack Warner’s personal collection, The Mystery of the Wax Museum is even more shocking today for its historicity. As students of film history, we have a certain set of expectations from the horror films of Classical Hollywood cinema. Curtiz and company upend those preconceptions, smashing away their polished mask to reveal an uncanny monster underneath.

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

Bibliography:

Everson, William K. Classics of the Horror Film. Citadel, 1995.

Koszarski, Richard (edited by). Mystery of the Wax Museum. The University of Wisconsin Press, 1979.

Robertson, James C.. The Casablanca Man: The Cinema of Michael Curtiz. Routledge, 1993.

Rode, Alan K. Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film. University Press of Kentucky, 2017.

Rosenzweig, Sidney. Casablanca and Other Major Films of Michael Curtiz. UMI Research Press, 1982.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review