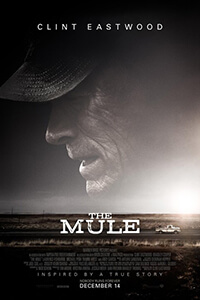

The Mule

By Brian Eggert |

Clint Eastwood has more than thirty directorial efforts under his belt, and his latest, The Mule, is among the least compelling of them. It’s the true story of a 90-year-old who somehow becomes a drug mule for a Mexican drug cartel. The screenplay by Nick Schenk, who also wrote Gran Torino (2008) in which Eastwood gave his last great performance, was based on Sam Dolnick’s 2014 article in the The New York Times, “The Sinaloa Cartel’s 90-Year-Old Drug Mule,” about Leo Sharp, the World War II veteran who became an “urban legend” after smuggling hundreds of kilos of cocaine into the United States for the notorious kingpin known as El Chapo. The title might also refer to the film’s version of Mr. Sharp, renamed Earl Stone and played, of course, by Eastwood. The character is a stubborn old bastard that refuses to budge in his bad behavior. He takes pride in his not-so-casual racism and feels entitled, presumably from his service to his country, to treat anyone that doesn’t please him like filth, including his family. But because it’s Clint Eastwood, we’re supposed to ignore the fact that Earl’s behavior is awful and find it all very amusing.

This is the second picture released in 2018 by the 88-year-old director, and the second that feels jarringly misguided, perhaps signaling that the screen legend either needs more dynamic material or has reached creative stagnation. This year’s The 15:17 to Paris, a disastrous effort this critic admittedly couldn’t bring himself to review, told the story of the 2015 Thalys train attack—but made the oddball decision to use the real-life participants in a work of problematic historical recreation, if not unabashed hero worship. A lot of Eastwood’s output has descended into hero worship in recent years, taking advantage of Hollywood’s new fascination with docubusters. American Sniper (2014) glossed over the less savory issues of soldier Chris Kyle to deliver a kind of actionized modern cowboy savior. He created conflict where there was none to exalt Chesley Sullenberger in Sully (2016), about the airline captain who safely landed a failing plane on the Hudson River. He even tried to turn J. Edgar Hoover into a sympathetic figure in the innate J. Edgar (2010).

Schenk’s script resituates the story from the early 2000s to 2017, from the Michigan area to Chicago, and makes Earl Stone a vet of the Korean War. When the film opens, Earl has spent most of his adult life basking in the minor celebrity he acquired from his horticultural work with daylilies, his devotion to which has led to his wife (Dianne Wiest) divorcing him and downright hatred from his daughter (Alison Eastwood). But when his business goes under, Earl finds that he now has more time for his family, though he’s faced with the fact that his lifelong attention to his career means that everyone except for his granddaughter (Taissa Farmiga) doesn’t want him around. Trying to make money to provide for his loved ones, belatedly, Earl gets in touch with the cartels through a random acquaintance (whose connection to Earl’s family is never adequately explained). He doesn’t bat an eye at becoming a transporter for several kilos of cocaine in his pickup truck and, after several runs, his ease behind the wheel soon earns him the trust of the cartel’s kingpin (Andy García).

Meanwhile, two DEA agents, Bates (Bradley Cooper) and Trevino (Michael Peña), investigate and come closer to pinpointing Earl, who goes by “Tata” among his fellow smugglers. The tension rises as Bates and Trevino receive pressure from the Special Agent in Charge (Laurence Fishburne) to show progress in their case, so they start pulling over black pickup trucks that look like Earl’s. There’s even a fateful Waffle House encounter, echoing a similar exchange between a cop and criminal at a diner in Heat (1995), where Bates and Earl partake in some loaded chit-chat. Cooper’s character is wholly underdeveloped, though there’s an implied parallel between Bates and Earl, as both are men who sacrifice their family life for their careers. Even so, we never get a look at Bates’ family. To further the tension, there’s also a subplot about a shift in power among the cartel’s leadership to a more domineering boss (Clifton Collins Jr.). The move leaves Earl’s handler, Julio (Ignacio Serricchio), who initially despises the nonagenarian but eventually comes to sympathize with him—despite Earl’s penchant for calling him a “Beaner”—helpless.

Meanwhile, two DEA agents, Bates (Bradley Cooper) and Trevino (Michael Peña), investigate and come closer to pinpointing Earl, who goes by “Tata” among his fellow smugglers. The tension rises as Bates and Trevino receive pressure from the Special Agent in Charge (Laurence Fishburne) to show progress in their case, so they start pulling over black pickup trucks that look like Earl’s. There’s even a fateful Waffle House encounter, echoing a similar exchange between a cop and criminal at a diner in Heat (1995), where Bates and Earl partake in some loaded chit-chat. Cooper’s character is wholly underdeveloped, though there’s an implied parallel between Bates and Earl, as both are men who sacrifice their family life for their careers. Even so, we never get a look at Bates’ family. To further the tension, there’s also a subplot about a shift in power among the cartel’s leadership to a more domineering boss (Clifton Collins Jr.). The move leaves Earl’s handler, Julio (Ignacio Serricchio), who initially despises the nonagenarian but eventually comes to sympathize with him—despite Earl’s penchant for calling him a “Beaner”—helpless.

The Mule should be called “The Adventures of the Incorrigible, Racist, Dirty Old Man.” Eastwood adopts his Gran Torino persona as a no-bullshit curmudgeonly bigot, except there’s no one around this time to correct his bad behavior. Some might call his casual racism humorous, but there’s nothing casual about the scene in which Earl calls a black family “negroes” to their faces and then laughs it off when they attempt to explain they don’t want to be called that. When he’s not spewing racial epithets, Earl is also a breed of old man that never stops complaining about people on their cell phones, a tiresome rhetoric to be sure. And then there are Earl’s seedier qualities, such as his penchant for hiring prostitutes on the road during his drop missions, his sexual virility meant as a charming aside. Or consider how the audience is subject to a sequence at the estate of García’s drug lord, where Earl dances with women four times younger than him, clinging to them like a pervy old man grasping at his last hope of sexual intercourse. This is followed by a tasteless bedroom scene where Earl beds two women ordered by the kingpin to do so. These are desperate, uncomfortable scenes that feel engineered by the screenplay, if only to suggest that Eastwood is somehow still sexually desirable.

The viewer must also pause to ask the question: “Is a drug mule who, after being captured, refuses to cooperate with authorities, but helps bring hundreds of kilos of cocaine into the country, someone that should be admired, simply because he served in the Korean War and committed his crimes at 90?” After all, think of the lives ruined because of the cocaine Earl trafficked. The judge didn’t think Earl should get off too easy; in the film and in real life, the man was sentenced to federal prison. But the script, at the last minute, turns Earl’s family into very forgiving people, if only so he might look sympathetic to the audience. Why Eastwood’s film would attempt to put Earl forth as an almost tragi-heroic figure, as someone who deserves the unabashed love of the family he ignored throughout his life, remains baffling, and an unearned moment of forgiveness. Aside from a few touching moments across from Weist, Eastwood’s character is one of the most unpleasant he’s ever played.

Of course, Eastwood’s direction is easygoing and straightforward. Yves Bélanger’s cinematography is capable and far less stylish than his usual work with director Jean-Marc Vallée (Dallas Buyers Club, Demolition). Like most Eastwood films of the last twenty years or more, The Mule is very easy to watch, at least formally. However, the material forces Eastwood’s movie star persona into Earl, blending the two in troublingly convenient ways that hope to distract from the ugliness of what’s happening onscreen. Notice how The Mule never shows the beheadings or bodies left in the wake of the cartels (it would be difficult to swallow a character like Earl as charming in Sicario, for instance). Eastwood seems to use the material as a swansong—one last go for the screen icon who cut his teeth on playing roguish heroes and womanizers. But the story doesn’t serve his apparent mission, and the entire thing proves rather embarrassing.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review