The Monkey

By Brian Eggert |

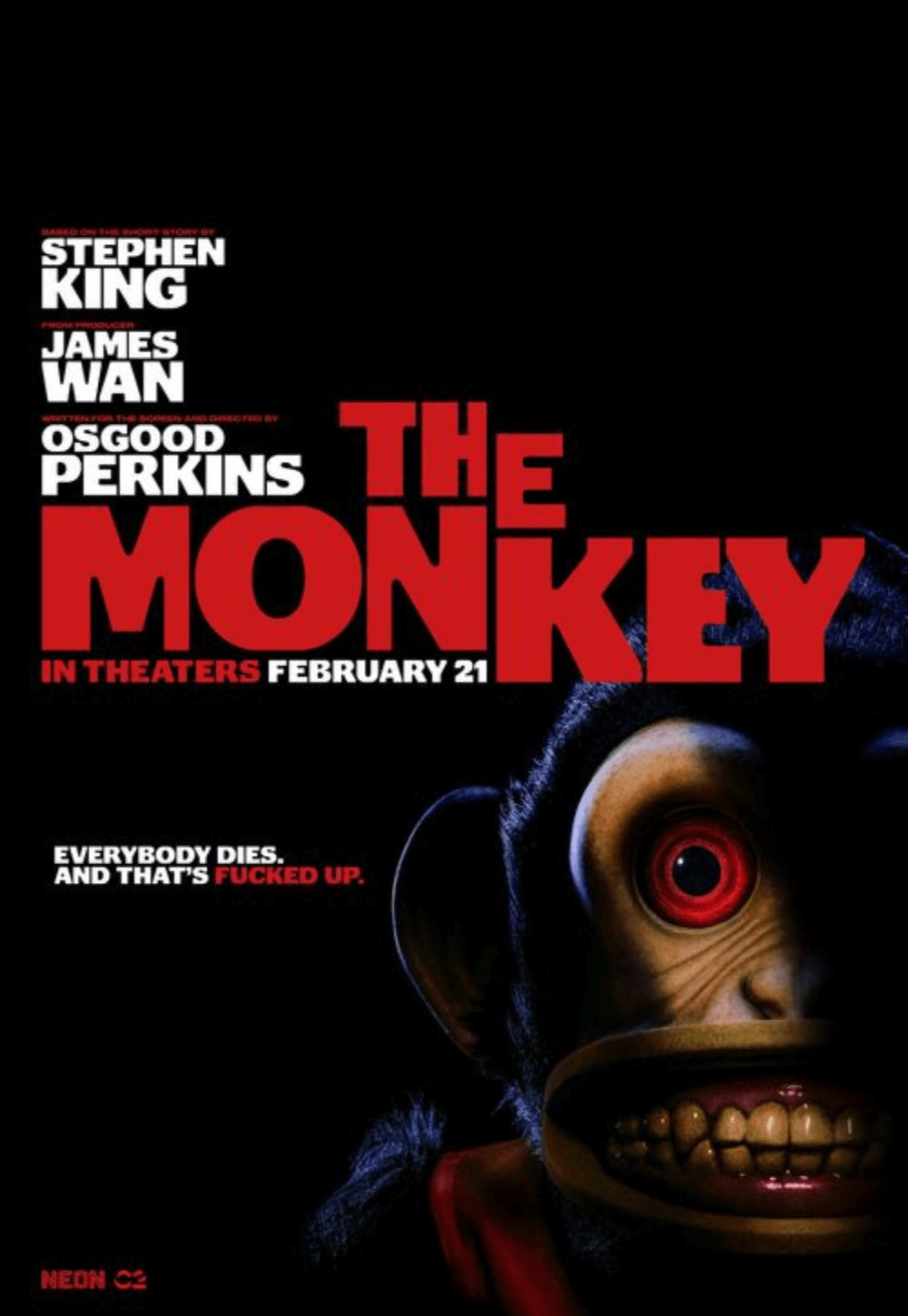

Osgood Perkins returns with another weird-for-weird’s-sake endeavor with The Monkey, an adaptation of Stephen King’s short story first published in 1980. The premise remains intact—whenever a wind-up toy monkey plays its tune (a clanging cymbal in King’s story, a beating drum in Perkins’ movie), someone dies randomly—but the writer-director’s additions prove insubstantial. Perkins adapts the material not by amplifying the existential dread of King’s concept but by cranking up the gore and injecting a dose of macabre humor into the proceedings. His treatment of the material never digs deeper than the amusing tagline on the poster: “Everybody dies, and that’s fucked up.” Except, where King’s story mainly dealt with everyday accidents and some unfortunate animal loss, Perkins has something more malevolent in mind: He uses the scenario as a platform to deploy an increasingly nasty series of splattery deaths meant to function as dark-humored punch lines. It’s not that this approach is innately bad, but in Perkins’ hands, it becomes monotonous.

Perkins’ follow-up to Longlegs, his breakout hit for Neon last year, which cost under $10 million and earned over $125 million, once again receives a significant assist from the independent studio’s crack marketing team: punchy red band trailers, creepy posters, and a hilarious email featuring rejection letters from major networks about Neon’s too-violent TV spot added to the buzz. All of this material points to the same message: The Monkey takes a comical look at random bloody death. Thanks to Greg Ng and Graham Fortin’s snappy editing, every death plays like a pie in the face. Each character who dies in the movie’s many freak accidents—impaled, trampled, run over, decapitated, electrocuted, shot—becomes a twisted source of humor. The appeal, I suppose, is that each shock prompts the viewer to involuntarily gasp and then laugh. Certainly, that happens once or twice amid the dozens of deaths in the movie. The more grotesque they are, the funnier Perkins seems to find them.

The story revolves around Hal and Bill Shelburn, identical twins whose father (Adam Scott) brought the dreaded monkey home. As youngsters, played by Christian Convery, Hal and Bill discover the monkey amid their father’s things in 1999, after he abandons the family, presumably because the monkey’s curse exposed him to too many horrible things. When Hal and Bill find the device inside a large round box, they read the label: “Organ Grinder Monkey,” and below that, “Like life.” The lesson Perkins hammers into the viewer’s brain is that anyone can die at any moment. Except, when it’s wound up, the monkey is compelled by some unfathomable force to select people at random for the most horrific deaths imaginable. So it’s less “like life” and more what the supernatural monkey (or whatever) commands. But that’s of little interest. As children, the more sensitive Hal and bullying Bill live with their mother, Lois (Tatiana Maslany, whose talents are wasted here), and witness several horrifying deaths of people close to them before finally resolving to drop the monkey down a well.

For twenty-five years, Hal (Theo James) has lived in fear that the monkey, which has an uncanny ability to reappear at random, will harm those close to him. In that time, he had a kid, Petey (Colin O’Brien), whom he has kept at a distance along with his estranged wife, fearing they would die if the monkey came back. And when it does, Hal reconnects with his acerbic brother (also James) to find the toy before Petey or anyone else gets hurt. Perkins’ script weaves together a story that, in other hands, might have resonated in its themes of father-son dynamics—how Hal and Bill’s fractured relationship with their father is mirrored in Hal’s distance from Petey. Similarly, a local oddball named Ricky (Rohan Campbell) with a sheepdog haircut wants to get his hands on the monkey, not for any nefarious purpose but because it reminds him of his late father. But less attention is given to these relationships than to delivering one death after another until the viewer develops a callus to the shock-value deaths. Yet The Monkey is a well-assembled movie, with Perkins making clear choices and executing them in competent visual terms, thanks to cinematographer Nico Aguilar’s textured lensing.

Production designer Danny Vermette gives everything a yellowish hue, suggesting Hal’s world is shabby and past its prime, worn down by years of fretting over the monkey’s return. Perkins uses plenty of practical effects to show bodies torn apart or crushed, and only a couple of surreal dream sequences enter the digital realm. The editing turns each grisly moment into a well-timed quip, finding humor in the most atrocious situations. However, Perkins’ writing and persistent ironic distance give the viewer little reason to care, which is something I’ve experienced in all of his directorial work thus far: The Blackcoat’s Daughter (2015), I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House (2016), Gretel & Hansel (2020), and Longlegs. When watching his films, I sense that he’s trying to be out-there and bizarre, but the attempt feels forced, unnatural, and unengaging. Along with the repetitive death humor, it’s all rather tiresome. Fortunately, James gives a solid, subtly straight-man comic performance as Hal, while his turn as Bill has an over-the-top quality that feels more attributable to the script than what James does with the role.

Filmmakers such as George Romero (Dawn of the Dead, 1978), Edgar Wright (Shaun of the Dead, 2004), and James Gunn (Slither, 2006) have turned gory deaths into comic moments with far greater success than Perkins does in The Monkey. It’s difficult to explain why his approach isn’t funny, except that it seems like someone who’s trying too hard, who doesn’t understand humor but tries to make his audience laugh anyway. I heard a smattering of laughter from viewers in my screening, but mostly, the reactions were muted. And similar to Longlegs, Perkins’ arch visual style often diverts attention away from the content of any given scene, ensuring that the viewer not only doesn’t laugh but also doesn’t feel any terror. The Monkey is an empty experience contingent on a single idea: that death happens to us all and how dreadful that is. But after it’s over, the movie reserves almost no space in the mind, leaving the audience neither happily diverted nor pondering the messed-up nature of mortality.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review