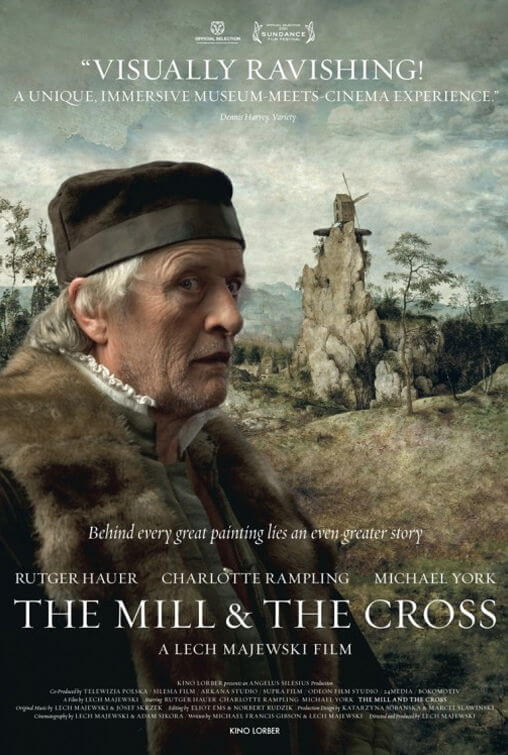

The Mill & the Cross

By Brian Eggert |

Jean Renoir once said that a film can be considered successful only if it thrives both as art and as a commercial product, because film, after all, is a business. This is paraphrased, of course, but the idea is sound. Perhaps this is why filmmakers like Alfred Hitchcock, Akira Kurosawa, Martin Scorsese, and Steven Spielberg are such masters of their craft—they combine art and commercialism into products that have entertained millions, but they have also redefined the artform with their desire to challenge the limits of cinema. The Mill & the Cross is a film, too, that challenges the limits of cinema, but its resounding failure resides in its lack of commercial appeal. The audience for this picture is a select few art historians that will appreciate Polish director Lech Majewski’s filmic examination of a single painting, namely Flemish master Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 1564 work The Way to Calvary.

Having earned an undergraduate degree in art history at university, during which time I focused on Bruegel’s work in the Northern Renaissance, the film immediately piqued my interest. Bruegel’s paintings, drawings, and prints are filled with humanity, in all its beauty and ugliness. We see this in his most famous works, such as The Peasant Wedding (1568) or Netherlandish Proverbs (1559), or my personal favorite, The Battle Between Carnival and Lent (1959). Each example explores a large landscape in which many tiny subjects, peasants, and grotesques, go about their daily routine as an overarching theme prevails in the work. In the case of The Way to Calvary, the subject is Christ’s crucifixion, although the actual scene is surrounded by hundreds of Bruegel’s characters, onlookers, travelers, and those utterly oblivious to what’s happening elsewhere in the painting.

Majewski’s film considers the painting from multiple perspectives. First, we meet Bruegel himself, as played by Rutger Hauer. Bruegel has been commissioned to paint The Way to Calvary by patron Nicholas Jonghelinck (Michael York) and chews over his composition. His structural model is a spider’s web, filling every individual cell with its own activity, from its finely detailed focal point center to its larger outreaching borders. Then, Majewski follows Bruegel into the painting itself, where we see stationary actors situated on a stage designed to look like the painting. A green-screen backdrop realizes a stunning CGI reproduction, painted by Majewski, which brings Bruegel’s work to life, gorgeous Bruegelian earth tones filling the landscape and costumes. It must be said that Majewski has created something extraordinary to behold in these shots, wholly unique to cinema.

Unfortunately, though he composes an incredible replica with human stand-ins, Majewski does very little of interest in there. His pace is slow, measured by long takes where little seems to happen. There is very little diegetic music and even less non-diegetic scoring. Unnamed characters from the painting earn banal subplots, although the word “plot” implies much more than we see. One compelling example follows a man and his wife who live a simple life with their calf. At the market, the man is attacked by Spanish troops, Catholics persecuting the Flanders Protestants, and he is tortured and put on display to become carrion for crows. His wife weeps under him for days. This imagery inspires Bruegel’s composition, replacing the Roman soldiers at Christ’s crucifixion with Spanish troops for modern relevancy. But there are others: A single mother with several children who run amok; Bruegel’s mother (Charlotte Rampling, forced to recite moody narration), who becomes his model for the Virgin Mary; a millworker who looks down from on high as a metaphor for God. But what about his fat wife? Elsewhere on the landscape, people are oblivious to such goings-on and set about their simple peasant lives.

Majewski’s structure works to explain, without a hint of subtlety, how the painting operates, and then mirrors Bruegel’s configuration on a smaller scale. Hauer’s Bruegel comes right out and says, This is what my painting means…, and defines the iconography and symbols employed, the prevailing metaphors. There are hundreds of individual subjects in Bruegel’s painting and Majewski’s approach captures about twenty; he spends too much time with too few characters. He renders Bruegel’s painting in undeniably impressive visual splendor but fails in capturing the energy, the hustle-and-bustle of the painting’s movement. There’s so much life in Bruegel’s work that he failed to capture in the film’s many long, quiet, dialogue-less scenes. In all, about 5 minutes of speaking fills a 90-minute feature. The meditative experience proceeds at a snail’s pace, proves flat, and only moderately rewarding, and even art historians may find themselves struggling to keep interested.

The film’s last shot pulls away from the painting on display in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum and denotes the museum-esque experience moviegoers were supposed to have. Instead of bringing a painting to life, Majewski has put a museum lecture to film. We appreciate the film from a distance, examining certain details here and there as Majewski’s small group of characters converges to assemble Bruegel’s full composition. But the journey isn’t an emotional or narrative experience, just a study of how a painter formulated a great painting. There’s undoubtedly a part of me—a pure art historian—that wants to grant The Mill & the Cross a better review. And if I were deep into Bruegel studies, perhaps I would, because there’s so much about Majewski’s film that brings an appreciation for the complexity behind Bruegel’s painting, and, indeed all of his work. But as a film critic who understands that a film must be more than a purely academic enterprise, Majewski’s film frustrated me. Though he has done something different and fascinating in concept, his execution is un-cinematic and lacks the same passion that he obviously feels for his subject. Rather than celebrating Bruegel’s painting, it feels like he does it a disservice.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review