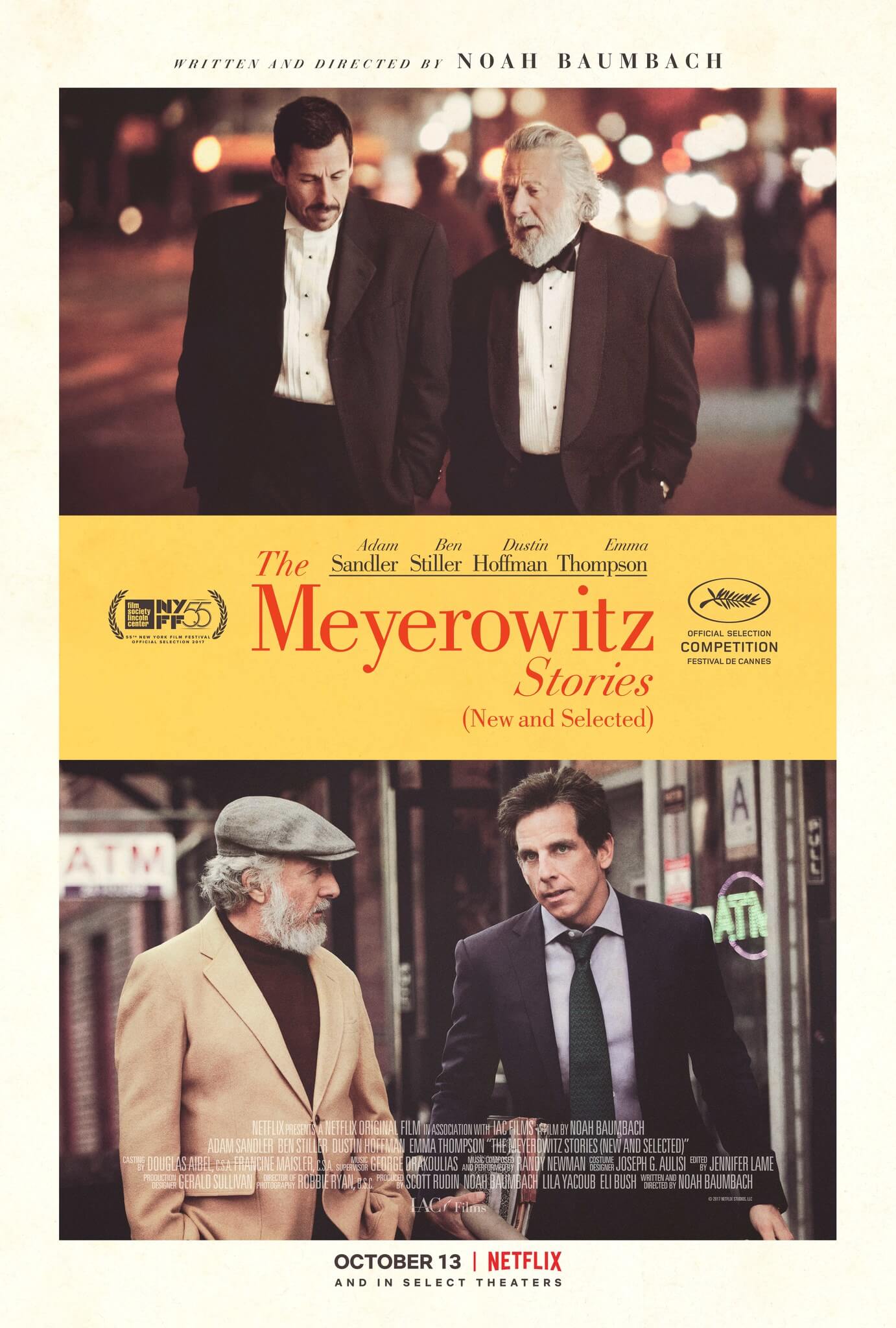

The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected)

By Brian Eggert |

In The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), a talented and self-righteous father sets impossible standards for the children in his wake. Which is not to suggest that he created those standards alone; rather, the children have also put undue pressure on themselves to compete in their complex family dynamic. Neuroses and unresolved tensions abound, the film comes from writer-director Noah Baumbach, who enters familiar territory explored in his 2005 work The Squid and the Whale, where two young teen boys suffer under the dueling egos of their intellectual and emotionally self-absorbed parents. Whereas that film explored the topic with grim and sometimes shocking humor in its representation of scathing, unearned self-satisfaction and hero worship, The Meyerowitz Stories offers frequent purely comic moments amid familial pain, offering a showcase for certain members of its talented but rarely well-utilized cast—including Ben Stiller, Elizabeth Marvel, and even Adam Sandler.

Netflix purchased the distribution rights to The Meyerowitz Stories earlier this year before its Cannes Film Festival debut, promising a very limited theatrical release to coincide with its premiere on the streaming platform. Sandler’s ongoing deal with Netflix has produced an abortive, offensively stupid series of films thus far—including The Ridiculous 6, The Do-Over, and Sandy Wexler (none of which this critic could endure for more than 15-20 minutes). Fortunately, The Meyerowitz Stories was produced independently by Scott Rudin and acquired on the open market, as many Netflix “originals” are, which places the film at a safe distance from the literal streams of diarrhea that appear in the other Netflix-Sandler efforts. And while its release on this platform may not be ideal for cineastes, the plan may ensure more viewers than Baumbach’s usual micro-audience see the film. What’s more, Baumbach somehow draws out a committed performance from Sandler.

Adopting those hesitant and unassured mannerisms that served him so well in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Punch Drunk Love (2002), Sandler plays Danny, a meek-voiced divorcé who, similar to his characters Happy Gilmore or Barry Egan, might blow his top if pushed. Danny used to play music (Sandler performs several of Danny’s original songs, hilarious, on the family piano) and has never had a career, though he’s helped raise his talented daughter Eliza (relative newcomer Grace Van Patten), a freshman film production major at Bard College. He returns to New York to spend some time with his father, Harold Meyerowitz, played by Dustin Hoffman. A moderately successful but far from eminent sculptor, Harold has produced three half-siblings from three marriages. Besides Danny, there’s Matthew (Ben Stiller), who, also divorced and father to a spastic child, runs his own financial consulting firm in California, and while earning more money than his father, remains underappreciated for his accomplishments. Their sister Jean (Elizabeth Marvel) hovers on the outskirts of the family, ever excluded.

Each of the children receives a chapter in the film’s episodic structure; they’re introduced with a title card, and then the story focuses on their perspective until the next chapter. However, Harold is central to the film, while his fourth wife, a bohemian alcoholic wonderfully portrayed by Emma Thompson in full passive-aggressive mode, lingers on the periphery. Danny attempts to connect with his father but finds Harold distracted and uninterested. Matthew at least receives some recognition from his mother (Candice Bergen, superb in her single scene), while his father proves incapable of acknowledging his downfalls as a parent. Jean seems to have accepted giving up hope in Harold. At some point, each of them must accept that Harold won’t change, but in order to get over their issues and move on, they probably should change themselves. Later, when the children are faced with Harold’s potential death, a hospital counselor recommends making five statements in the time they have: “I love you. I forgive you. Forgive me. Thank you. Goodbye.”

Each of the children receives a chapter in the film’s episodic structure; they’re introduced with a title card, and then the story focuses on their perspective until the next chapter. However, Harold is central to the film, while his fourth wife, a bohemian alcoholic wonderfully portrayed by Emma Thompson in full passive-aggressive mode, lingers on the periphery. Danny attempts to connect with his father but finds Harold distracted and uninterested. Matthew at least receives some recognition from his mother (Candice Bergen, superb in her single scene), while his father proves incapable of acknowledging his downfalls as a parent. Jean seems to have accepted giving up hope in Harold. At some point, each of them must accept that Harold won’t change, but in order to get over their issues and move on, they probably should change themselves. Later, when the children are faced with Harold’s potential death, a hospital counselor recommends making five statements in the time they have: “I love you. I forgive you. Forgive me. Thank you. Goodbye.”

Baumbach also co-wrote The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004) and Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) alongside Wes Anderson, both films about the tensions that emerge from a celebrated patriarch. Along with The Squid and the Whale and The Meyerowitz Stories, the filmmaker has explored the anxieties and complexes that result in having intelligent, priggish parents, drawing from his own family experiences (his parents were both critics and writers). While Hoffman is excellent as an oblivious and narcissistic force, with Harold never willing to admit his own failings as a parent or artist, he retains a distant tenderness that serves the character, and film, well. Sandler’s Danny limps about from a bad hip, ignoring the pain just as his father ignored his own medical issues, allowing the actor to capture the sensitivity and vulnerability of his character. Stiller has only been better in Baumbach’s Greenberg (2010). Marvel receives less screen time, but she has many of the film’s biggest laughs.

The Meyerowitz Stories is also one of Baumbach’s funniest films. Although much of it occupies a chatty mode that might be compared to dialogue-based comedies of Woody Allen, he also uses broad humor and editing to achieve a laugh. Take an early scene when Danny is trying to find a parking spot in the cramped East Village; he begins shouting at another driver in that explosive Sandler way, and mid-rant, the shot cuts to something else. Baumbach and editor Jennifer Lame cut early or cut-in on a compromised moment, making excellent use of comic timing. Elsewhere, Eliza’s bizarre student film projects employ affront sexuality, feminist commentaries, and animal costumes for maximum discomfort when the family gathers to watch. Of course, Baumbach has attested to his love of classic screwball comedies from Preston Sturges (The Lady Eve, Sullivan’s Travels), and he delivers a sibling fight between Danny and Matthew, followed by awkward speeches at a retrospective for their father’s artwork, that achieves absurd and comedic heights.

As always, Baumbach’s technical presentation is impressive and controlled. Shooting in autumnal colors in and around New York, cinematographer Robbie Ryan captures oranges and muted tones, signaling the film’s themes about letting go of old wounds for a period of dormancy, after which, with any luck, everyone can find a sense of rebirth—but not before several sequences of emotional and situational exasperation. Randy Newman provides a subtle and sensitive score, with an end credits song to remember. The performances from the entire ensemble (which includes amusing guest appearances from Judd Hirsch, Adam Driver, and Sigourney Weaver) are outstanding, with several potential awards contenders among them (Hoffman and Sandler above all). And though dysfunctional families are hardly new territory for the filmmaker, Baumbach finds new ways, new senses of humor, and new characters to explore from a profound, affecting perspective. The Meyerowitz Stories stands among Baumbach’s best work to date, and one of the best things to debut with the Netflix brand.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review