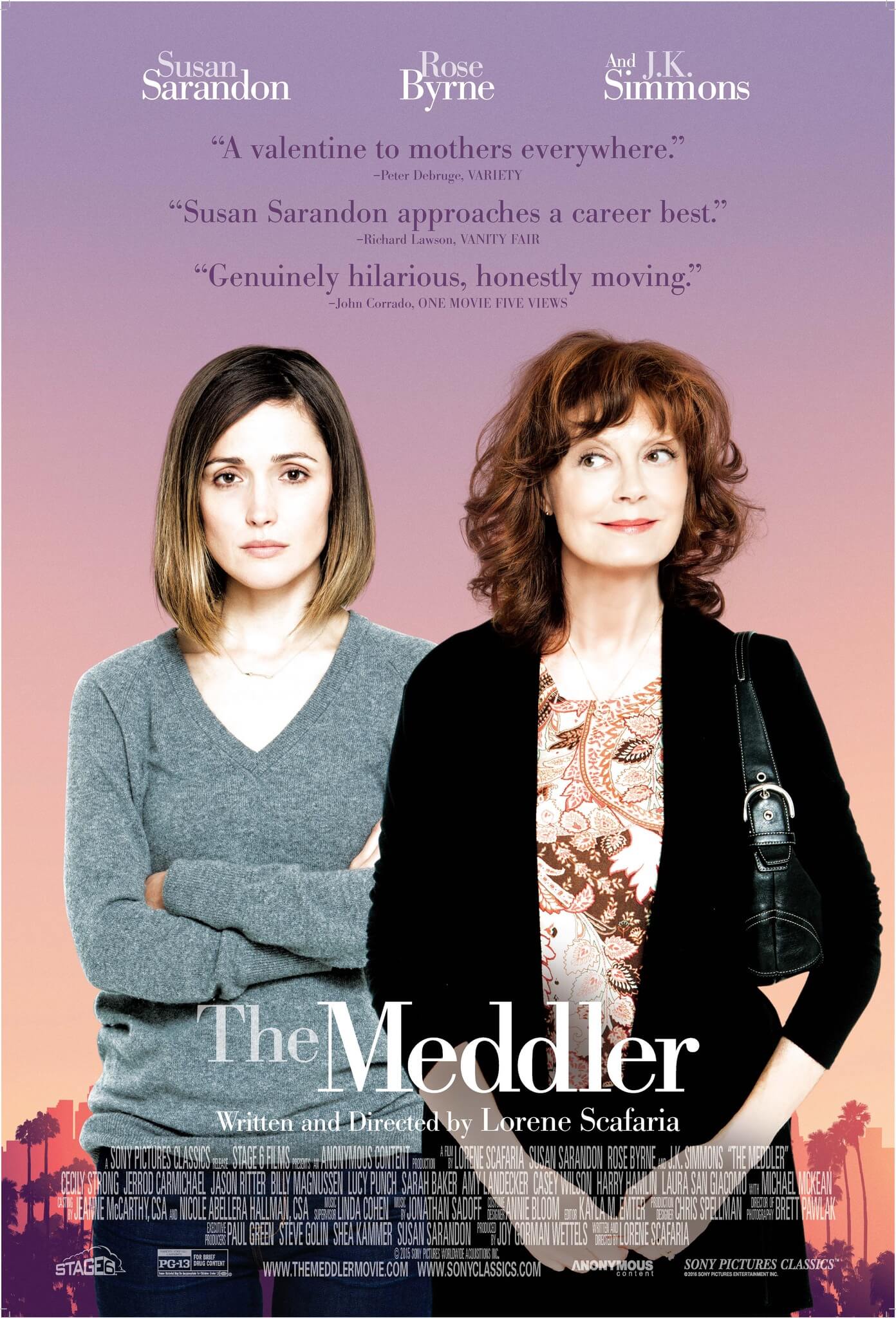

The Meddler

By Brian Eggert |

Sentimentality is extremely difficult to do well. Too much sentiment results in a mawkish, saccharine, and transparent quality. Too little can feel empty and dry, leaving the viewer unaffected. Lorene Scafaria achieves a pitch-perfect harmony of comedy and earnestness in The Meddler, her second film as writer-director after the grossly underrated Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (2012). Though her sophomore effort may, on the outside, appear standard and familiar, the result has been executed with a rare kind of sincerity seldom found in films today. Scafaria draws on her deeply personal experiences with her mother and delivers a dramedy that contains the requisite laughs and tears. Without a moment requiring guilt to justify our reaction, The Meddler feels naturally funny, effortlessly charming, and endearing throughout.

Susan Sarandon plays Marnie Minervini, a mother in her sixties who has moved to Los Angeles to be closer to her fraught daughter, Lori (Rose Byrne, rarely better). Lori has just broken up with her actor boyfriend, Jacob (Jason Ritter), and she’s under pressure to finish a script for her TV pilot. Though Marnie wants to be supportive, she isn’t helping. She’s the kind of well-meaning mother who calls and leaves long messages on voicemail describing every detail of her day, and when she doesn’t receive an immediate callback, it’s followed by more calls, voicemails, and texts. Or she just arrives at her daughter’s doorstep in the morning unannounced, bag of bagels in hand. She also holds firm to the belief that Lori and Jacob will get back together, even though it’s clear he’s moved on. Marnie might be perceived as downright monstrous in another film, but she’s treated with a rare sort of integrity in The Meddler.

Scafaria has written a three-dimensional character, and Sarandon imbues her with a lively, good-hearted spirit, but also a wounded side. A widow, Marnie helps wherever she can, volunteering at a local hospital and babysitting for Lori’s friends. After receiving help from an Apple Store clerk (Jerrod Carmichael), she offers to drive the young man to and from night school, which she suggested he attend. The title might threaten to pigeonhole the character, as she’s far more than an interfering motherly presence. The loss of her husband and Lori’s father Joe, an Italian immigrant seen only in photographs, has left them both wounded. Marnie refuses to pick a gravestone or do anything with her husband’s ashes. During a trip back to New York, she visits Joe’s family and remarks about the one-year anniversary of her husband’s death; but Joe’s family corrects her that two years have actually passed. Her loss still feels so close, the wound still fresh, leaving her to occupy her life with distractions—much to the irritation of Lori, and the delight of others on the receiving end of Marnie’s generosity.

Sarandon plays Marine with personality to spare, in part because Scafaria’s writing gives the actor plenty to work with, but also because the actor allows herself to disappear into the role. In the very first seconds of the film, Sarandon’s accent may seem heavy-handed, but after a moment it becomes easier on the ears and even endearing. Her quirks never seem forced, in part because she’s more than just a mother character—she’s also a romantic lead in a very effective love story. She’s pursued in unwanted advances from a suitor (Michael McKean) and later hesitates to become involved with Zipper (J.K. Simmons), an ex-cop who rides a Harley and tends chickens. What I love about Marnie is her openness to the world. Though she could have recoiled in grief, she embraces the unknown and tries new things. This behavior is also delicately tragic, as she’s trying to distract herself from her grief. When Lori realizes as much, the character becomes more than just an annoyed daughter, but another wounded character struggling because every time she looks at her mother, she thinks of her father.

Sarandon plays Marine with personality to spare, in part because Scafaria’s writing gives the actor plenty to work with, but also because the actor allows herself to disappear into the role. In the very first seconds of the film, Sarandon’s accent may seem heavy-handed, but after a moment it becomes easier on the ears and even endearing. Her quirks never seem forced, in part because she’s more than just a mother character—she’s also a romantic lead in a very effective love story. She’s pursued in unwanted advances from a suitor (Michael McKean) and later hesitates to become involved with Zipper (J.K. Simmons), an ex-cop who rides a Harley and tends chickens. What I love about Marnie is her openness to the world. Though she could have recoiled in grief, she embraces the unknown and tries new things. This behavior is also delicately tragic, as she’s trying to distract herself from her grief. When Lori realizes as much, the character becomes more than just an annoyed daughter, but another wounded character struggling because every time she looks at her mother, she thinks of her father.

Scafaria based the story on her own experiences with her mom, named Gail, who like Marnie moved out California after her husband, the director’s father Joseph, also an Italian immigrant, died. According to interviews with the writer-director, she borrowed whole scenes from real life, such as when Marnie visits Lori’s psychiatrist hoping to discover what’s on her daughter’s mind. Instead, the therapist asks Marnie if she’s spending so liberally because she feels guilty that her husband left her all that money, as though the money is some kind of unworthy replacement. Marnie poo-poos the idea, as she sits surrounded by Crate & Barrel bags from a recent spree. Or consider the subplot where Marnie offers to pay $13,000 so Lori’s lesbian friend can finally have a proper wedding ceremony. Gail actually did as much for this film’s producer, Joy Gorman Wettels.

The Meddler could have been a very different kind of experience in the wrong hands. Imagine an alternate, more sitcom-esque version that reduces the mother character to a wacky, one-dimensional type, and reduces the fed-up child to a petulant jerk. Everyone in this lesser version behaves like a trope, and the plot follows the same basic narrative arc, but without any of the humanity. In fact, such a film was already made in 2007 and it’s called Smother, starring Diane Keaton, Liv Tyler, and Dax Shepard, about a mother who moves in with her son and pesters him to get his life organized. And though Scafaria’s film follows a familiar trajectory, not a single moment feels untrue, because she’s writing from experience, and from the heart. The genuine humor and emotion recall Albert Brooks’ dramedy Mother (1996).

The director also avoids familiar devices like an overly commercial soundtrack or treating Los Angeles as a character within the film. When a couple of Beyoncé songs earn playtime on Marnie’s radio, they’re used endearingly as part of their respective scenes (in fact, Marnie quotes Beyoncé lyrics in one of the film’s most touching moments). Likewise, Zipper’s affinity for Dolly Parton lends a certain authentic quality to the character. Regarding formal presentation, Scafaria’s choices are solid, allowing the story’s heartrending drama its due. Take the subplot involving a mute elderly patient at the hospital where Marnie volunteers, and the simple profundity when she realizes what the patient has been trying to tell her all along. But there are a dozen or more other laugh-out-loud moments throughout the film as well, such as when we finally discover why Lori doesn’t want her mother to say “Shoot the pilot” about her TV show.

Feel-good films about families or the bonds between mothers and daughters have the capacity to feel cloying and too syrupy. Rare titles do this well, like Terms of Endearment (1983) or Little Miss Sunshine (2006). They make us laugh and cry, balancing humor with raw, guilt-free emotion. The careful equilibrium required to achieve a successful feel-good picture is especially difficult with today’s audiences, who are generally more cynical toward a crowd-pleasing moviegoing experience. In recent years, few films have managed this balancing act as well as The Meddler, which is the kind of film bound to get (criminally) overlooked come awards season because of its generic poster and unremarkable title. What Lorene Scafaria accomplishes here is deceptively simple, yet also profound and joyous. In the feel-good genre, few films stand out as more than formula and schmaltz. But Scafaria has made one of the best films of its kind.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review