The Matrix Resurrections

By Brian Eggert |

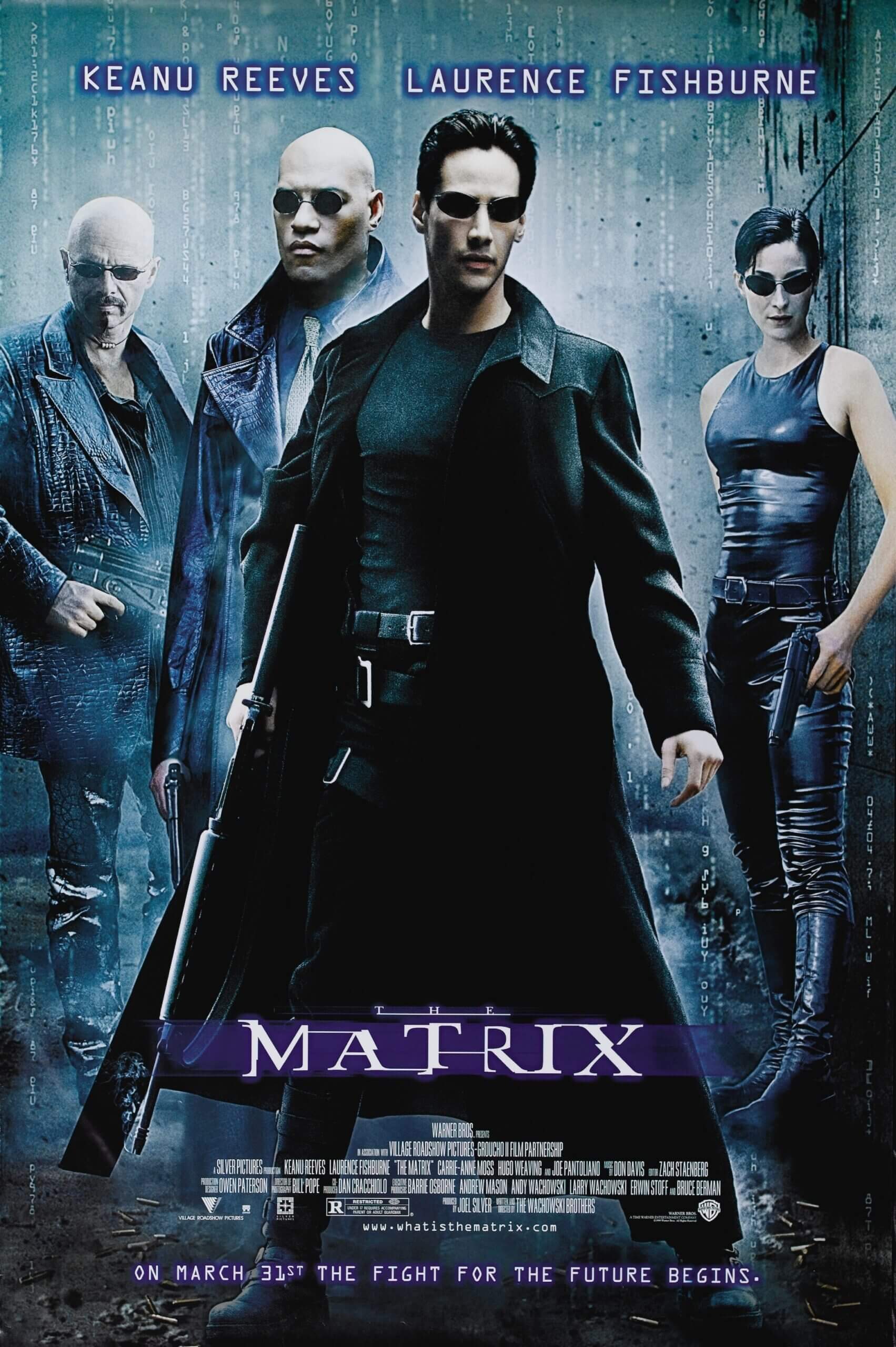

If anything prevents me from loving the Wachowskis’ original Matrix trilogy or ranking it among the best science-fiction series, it’s the lack of emotional connections among characters. For a story that places people against a world controlled by robots and advanced artificial intelligences, its attention on what makes humanity special remains limited. Memorable action, impressive fight sequences, and highly interpretable philosophical ideas aside, its main characters lack human depth. How does one describe Neo’s personality, besides a self-doubting hero propelled by the exposition of other characters? What makes Neo and Trinity fall in love, besides being told they’re fated to do so? The insufficient answers to these questions leave the trilogy admirable for its influence on Hollywood filmmaking and prompting scholars, critics, and casual viewers to interpret what the Matrix represents. But it’s a rather cold experience. The Matrix Resurrections continues in that tradition, delivering an exercise in elaborate action and intriguingly self-aware ideas with a familiar set of monomyth characters fulfilling their obligatory roles.

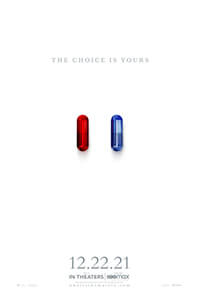

Lana Wachowski directs solo this time around, collaborating with two novelists on the screenplay: David Mitchell, whose Cloud Atlas the Wachowskis adapted in 2011, and Aleksandar Hemon, who contributed to the Wachowskis’ Netflix show, Sense8. Together they compile a sequel-reboot-spinoff thing that feels like a personal statement wrapped in a big-budget extravaganza. When Wachowski reintroduces Neo as a video game designer who, once more named Thomas Anderson, created a series of popular games called The Matrix years ago, she establishes a meta-infused version of her own experiences inside of pitch meetings, where Warner Bros execs tell her that she needs to make a sequel or they’ll hire someone else. There, our anxiety-ridden yet sedated hero listens to the brash Jude (Andrew Lewis Caldwell) discuss what the sequel should be. Jude and a game development think tank spout off about the original’s appeal—its themes of free will versus destiny, trans politics, capitalist dogma, and simulation theory. But most of all, Jude wants to see “bullet-time”—the back-bending effect that allowed Neo to dodge bullets. (Note their failure to mention a powerful love story.) Doubtless, Wachowski had the same meeting where she was coerced into making this sequel after Warner Bros threatened to continue her franchise with some studio plugin.

The new plot entails a group of human freedom fighters, headed by the spirited Bugs (Jessica Henwick), who discover the robots have secretly kept Neo and Trinity (Carrie-Ann Moss) alive. In the opening scenes, Bugs enters a modal—a Matrix video game within the larger Matrix—to release a game version of Morpheus (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II) who has achieved sentience. As it turns out, computer programs can now develop a consciousness that can be freed from the Matrix simulation and enter into the real post-apocalyptic world in robotic bodies. The humans have been freeing programs, called Sentients, from the Matrix and live with them in harmony. Indeed, this is no longer a story about all of humanity warring against every robot; it’s about assessing individuals and realizing the world isn’t so binary. Naturally, the theme gives way to barely subtextual remarks about transgender and fluid identities—all of which felt hinted at in the original three films but has more room to breathe since Lana’s transition and our decidedly more trans-positive society.

The Matrix Resurrections has some fun establishing Neo’s place in the new Matrix as a dissatisfied game designer, and there’s plenty of comic relief built around his mentally fried character floating through life, subdued by his prescription of blue pills. The film is funner than its predecessors, allowing for plenty of Easter Eggs and winks at the audience. But it comes with an overdependence on flashbacks and “remember when” scenes inserted into the mix, justified as cutscenes from Anderson’s game. Still, the film’s dependence on what came before leads to plenty of revisions: Whereas the Wachowskis helped popularize cyberpunk concepts and the burgeoning potential of the internet with their 1999 original, the world has since caught up to them. Accessing the Matrix is no longer about finding a landline—an almost foreign concept for today’s younger viewers—but moving through mirrors. Neo’s archnemesis Agent Smith now appears in a new “skin,” played by Jonathan Groff. And while there’s hardly a need to explain why, other than Sentients have thoughts and desires to change their appearance too, we might wonder why Groff’s version seems like Smith in name only—the character acts more cartoonish and chummy here than Hugo Weaving’s sneering, insidious version.

Unfortunately, the film’s move toward self-awareness and irony leads to other unsubtle choices. Consider the Analyst (Neil Patrick Harris), the string-pulling AI that chose to keep Neo and Trinity alive. Played with all the snark Harris can muster, the role is saddled by dialogue that feels like the writers commenting on our world rather than the world of the movie. “Women used to be so easy to control,” the Analyst remarks. It’s not that the content of the statement feels bothersome; instead, such comments feel more appropriate for our post-#MeToo world than the narrative space of the Matrix. And so, when Trinity eventually develops the same powers that Neo once had, it’s less justified within the story mechanics than the extratextual atmosphere of feminist gender politics in which Wachowski made the film. The notion of giving Trinity the power is inspired, but the screen story’s logic that facilitates its modern-day commentary feels forced. Trinity emerges with those powers because the filmmakers want her to, but the story mechanics don’t justify the development.

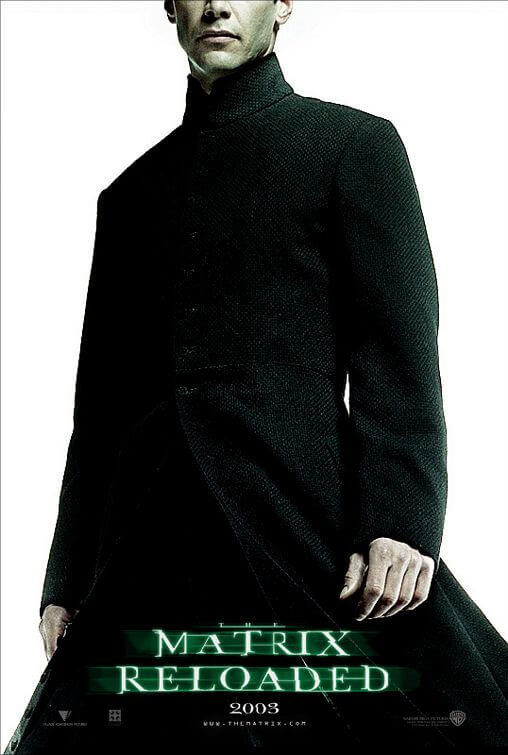

The screenplay has the same problems that Reloaded and Revolutions had, including a structure that consists of exposition dumps situated between scenes of action. But where the other sequels featured memorably crafted and occasionally mind-blowing sequences—such as a stunning freeway chase or robot attack in an underground stronghold—Resurrections doesn’t have any clear standouts. Rather, the action sequences feel slapped together by editor Joseph Jett Sally. For example, a train scene featuring our heroes attacked by agents (who have upgraded to automatic weapons instead of pistols) looks hastily assembled and results in visual confusion. Likewise, martial arts sequences feel like obligatory inclusions, almost an afterthought rather than high-impact centerpieces. And with Reeves older and a little stiffer, his scenes of action have been limited to Neo holding his hands up and blasting opponents with his mental powers. As for bullet-time, Resurrections employs blurry slow-motion that, in an alternative to bullet-time, allows a villain to move even faster than his ultra-slo-mo counterparts. It’s a neat enough idea, but it doesn’t boggle the mind or delight the eyes. A day after watching Resurrections, I struggled to recall a single action sequence that felt iconic or held a place in my memory.

What lingers afterward is Lana Wachowski’s outpouring of frustration about how the world has changed for the worse since the original movies. “The Matrix won,” observes one character, and the notion of “truth” has been weaponized against people. Despite the original film’s warning in 1999 at the dawn of the Digital Age, people have not only flocked to the internet for salvation, but they have also created subcommunities and ideological bubbles that make up their own rules for reality (“Real—there’s that word again”). Fictions take precedence in our lives because they feel real, and we continue to build them up without a critical thought because they feel safe and proper. The internet is a space where every search result has been optimized to validate your opinions, no matter how absurd, and where your bookmarks represent your virtual universe. In the new Matrix, Agents no longer appear as though they work for the Secret Service; now, they can look like anyone—your friends and neighbors. So beware. And even while Resurrections laments some of the ways our world has devolved in the last two decades since moviegoers last saw Neo and the gang, it celebrates other developments in a way that feels personal for Lana Wachowski and the trans community. But that’s just one reading.

The appeal of this franchise has always been its use of traditional narrative motifs that prompt countless allegorical interpretations, leading to expansive essays and books written about its pop-philosophical approach. Resurrections will be no different. However, it’s less cohesive than its predecessors in formal terms, even if Wachowski and her co-writers inject a wellspring of intriguing ideas. The film’s meta-ness about the earlier films and how the world responded to them, along with its commentary about the banality of exploitable intellectual property, earn the new sequel plenty of self-awareness points (although, some of the callbacks play ironically, while others seem like genuine touchstones of the series). But the film falters from its lack of memorable action scenes that sear themselves into our minds (the minimum requirement of any Matrix film), and worse, characters who feel like mere avatars for the writers’ ideas and remarks about our world than human beings motivated by emotions. I’m thankful that Wachowski convinced a major studio to give her such a platform, but I wish it made me feel more.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review