The Matrix Reloaded

By Brian Eggert |

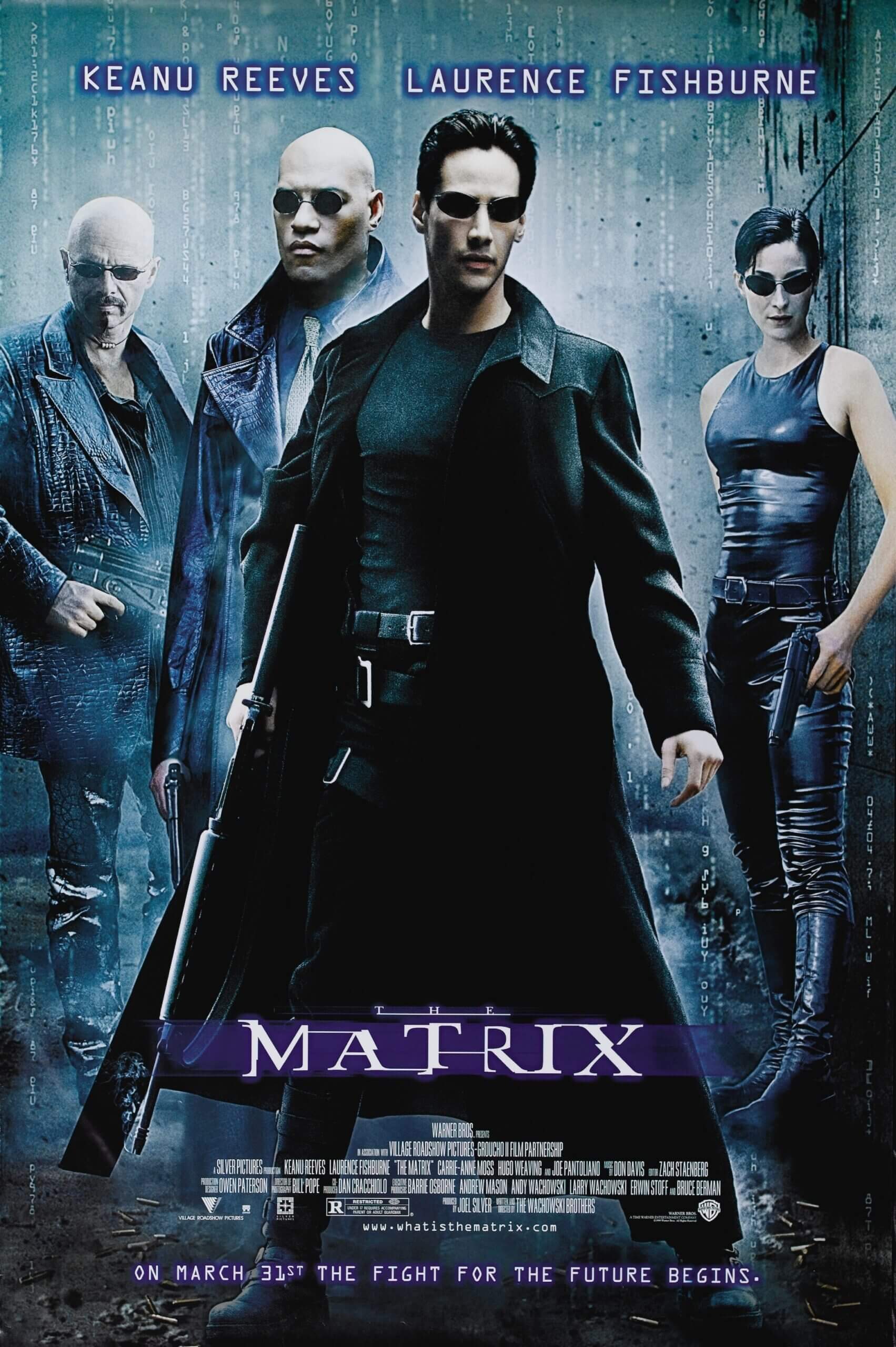

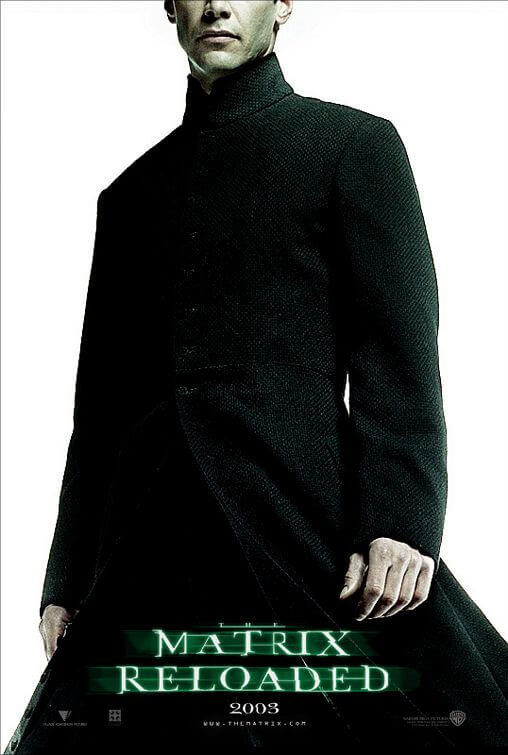

Four years after The Matrix, hype for the sequel set expectations impossibly high. The Matrix Reloaded arrived in theaters in May 2003 and quickly curbed enthusiasm for the final entry in the Wachowski siblings’ trilogy, The Matrix Revolutions, which followed that November. The first sequel underwhelmed on several fronts, but a tremendous visual sense and action sequences were not among them. Ever the visualist filmmakers, the Wachowskis conceived elaborate and daring action set-pieces that remain impressive more than a decade after its release. But not even their considerable talent could make lightning strike twice, at least not with the same degree of voltage. As a result, The Matrix Reloaded feels merely like an episode in a larger saga that attempts to dwarf its predecessor but then doesn’t. Through its lack of self-containment, it refuses to engage the limitless possibilities promised at the end of the first film. That aside, the sequel entertains and occasionally impresses, despite its unavoidable failure to execute its impossible task in a satisfying way.

The Wachowskis once again shot in Australia, where costs were cheaper, though they moved from a relatively small budget ($44 million for The Matrix) to more than three times that for the sequel. Because the original proved so popular, talk of the Wachowskis’ complex requirements hit the industry. Such reports fed the flames of anticipation long before the films were released: a car chase for which the filmmakers created a 1.5 mile stretch of highway built on a former Naval Air Station in Alameda, California; a fight sequence requiring computer and camera technology far beyond what was popularized by their “bullet time” sequences in The Matrix; a gravity-defying fight in which the combatants dodge not bullets but swords. All were ambitious ideas that would, hopefully, be reflected in the film’s story.

Though many critics received the film with a combination of lukewarm praise or altogether dismissal, The Matrix Reloaded went on to make $281.5 million in domestic grosses and plenty more worldwide. However, many viewers, this one included, consider it one of the most disappointing sequels of its time. The critic for The Hollywood Reporter correctly assessed the co-directors’ storytelling faults, observing the story “stumbles frequently […] as the movie stops cold for philosophical digressions about fate and destiny and reality.” The Wachowskis’ brand of over-complicated exposition makes a relatively simple idea seem byzantine, as though no one inside The Matrix can speak in Layman’s terms or anything but riddles. In many cases, the screenplay is too clever for its own good—whereas The Matrix took its time to establish its one or two head-spinners (for example, explaining what The Matrix itself is)—the sequel tries to blow our minds with several philosophical turns, each one of them elucidated almost exclusively through multifaceted metaphors, which are then quickly forgotten during the following action sequence. For example, Lambert Wilson’s ostentatious character, The Merovingian, explains how some otherwise inexplicable events in The Matrix (such as ghosts) occur because they are actually rogue programs that exist outside of the Matrix’s written rules—but he explains it in the most impenetrable way imaginable.

Many of the ideas in The Matrix Reloaded are intriguing but, at the same time, remove humanity from the equation. The sequel picks up shortly after the events in The Matrix, when the prophesied hero Neo (Keanu Reeves) dreams of his lover Trinity (Carrie-Ann Moss) dying in a gunfight. Events soon unfold that set Neo on a mission to protect the human survivors of the machine-ruled post-apocalypse from an oncoming invasion of their underground city, Zion. To do this, Neo will have to destroy a power plant inside the Matrix, the same plant where Trinity dies in his dream. But before Neo and company can infiltrate their target, he has to find rogue programs, hiding in The Matrix under the guise of eccentric human beings, to assist him. At the same time, Morpheus (Lawrence Fishburne)—now presented as a kind of religious fanatic obsessed with the idea of The One and opposing the disbelieving officials in Zion—takes a lone ship and enters The Matrix to wait for instructions from The Oracle (Gloria Foster). Meanwhile, the thought-dead Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving) reappears and duplicates himself somehow. Along with dozens of clones, he plans to exact revenge on Neo.

The film’s main downfall is a deficiency of humanity, which is odd given that the major conflict is between humanity and robots. Characters such as the much-built-up Seraph (Collin Chou) present interesting ideas but then recede into the erratic directions of the plot. In addition, forced scenes meant to build an emotional connection—the dance sequence in Zion, the love scene between Neo and Trinity, the comic relief by Link (Harold Perrineau)—feel less natural than obligatory. This may be a structural issue, as the Wachowskis have broadened the scope of their world and added more characters, therein losing focus on Neo’s journey to realizing his destiny to become The One, and all that that entails. Zion politics and society, Agent Smith’s almost unconnected duplication subplot, and the invasion of Zion by machines create the narrative’s stakes. Still, they have little to do with Neo himself for the moment. And while the film opens with Trinity’s death foreseen in a dream, the Wachowskis again under-develop the central relationship that would otherwise make her death as emotionally devastating as it could have been. Ultimately, too many characters and too few dramatic storylines leave The Matrix Reloaded a flat, if diverting experience.

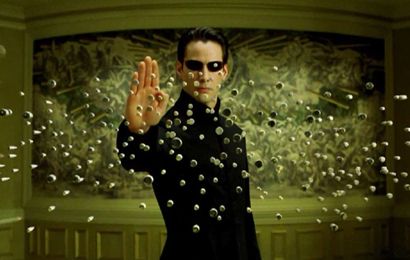

While the Wachowskis use characters like The Merovingian, The Keymaker (Randall Duk Kim), or The Architect (Helmut Bakaitis) to explore the limits and possibilities of the cyberpunk world they have created, unlike The Matrix, they rarely use their action sequences as devices in support of their narrative. Long philosophical discussions are inserted between and wholly separate from the combat sequences, and the film lacks cohesion as a result. Moreover, though the thrilling freeway chase proves a wowing piece of action thanks to real cars on a controlled course, other sequences look underwhelming. Take what has been called the “burly brawl,” where Neo fights off upwards of 100 Agent Smiths, or the ghostlike Twins (Adrian and Neil Rayment), who can phase through solid matter—these CGI creations look like videogame fodder today, and because of this, they fail to astonish as they should. Still, cinematographer Bill Pope works with his directors to achieve a slick-looking polish from start to finish, and the enduring style remains consistent even when the story does not.

Many of these story elements entertain and impress as individual scenes. But upon close inspection, their relation to one another is an illusion. By the end, The Matrix Reloaded plays like a chess piece that has made several deliberate moves and ultimately sacrifices itself to save the Queen, which is the final film, The Matrix Revolutions. It establishes many ideas and subplots, more than one review can cover, but few of them go anywhere significant. And by the last entry, they’re altogether forgotten. The sequel’s jumbled storytelling is less apparent on home viewings when the trilogy’s completion is just the change of a disc away, but on its own, The Matrix Reloaded contains much that is superfluous. Whole sequences where characters exchange dialogue and fisticuffs feel added for no other reason than “Wouldn’t it be neat if…?” This would be fine if there were a heavier dramatic pull, except emotional characters were not a strong suit of The Matrix, which stands as the lingering quibble for the trilogy as a whole. However, as stated above, the film entertains despite its structural shortcomings, as the Wachowskis have created a cinematic world that’s a pleasure to experience, even though it’s not as satisfying as its predecessor.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review