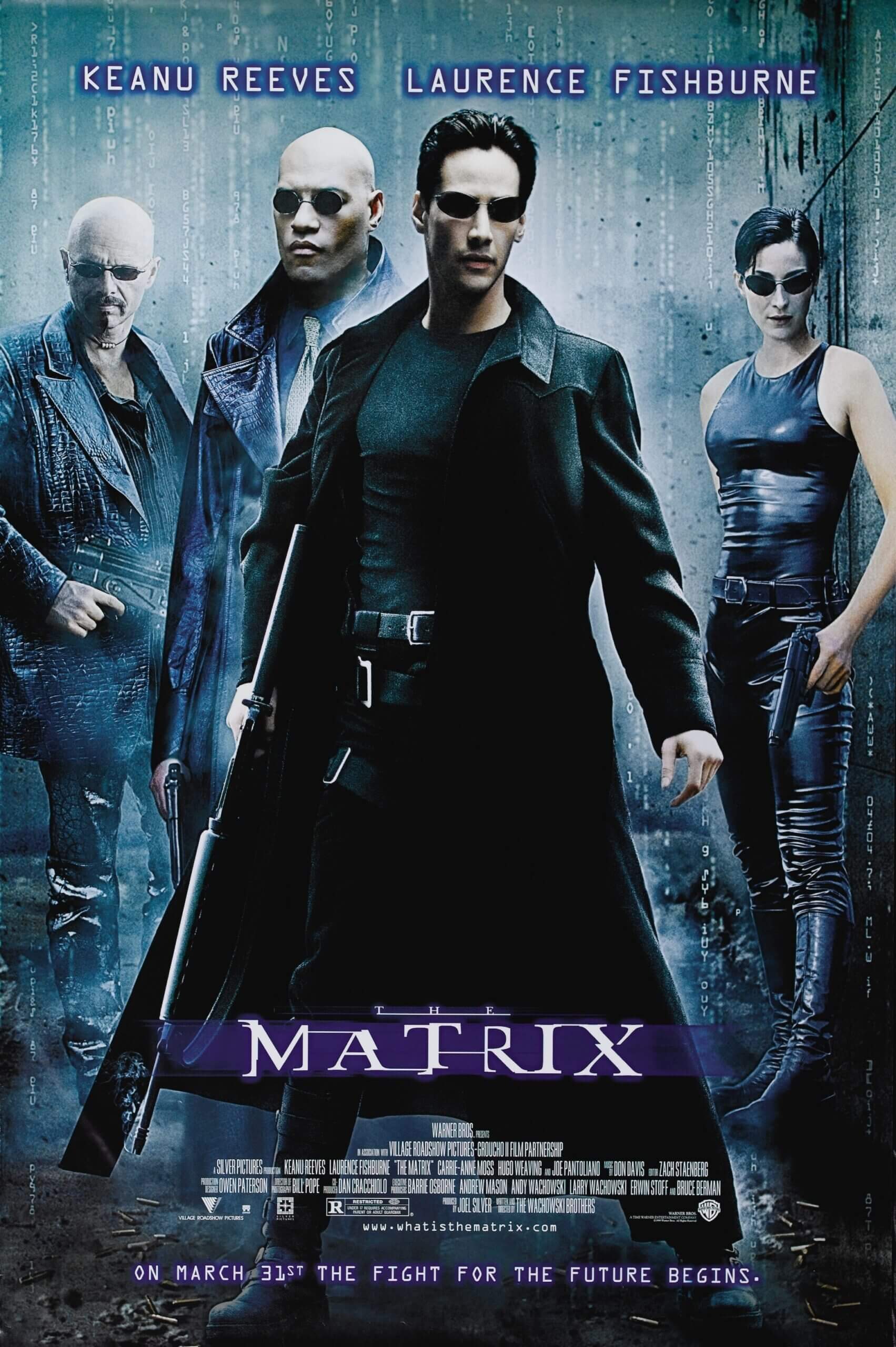

The Matrix

By Brian Eggert |

In 1999, the Wachowski siblings released a strange mix of bravado special FX, elementary philosophy, martial arts-laden combat, and mind-bending plotlines in an influential science-fiction actioner. The Matrix became a phenomenon ripe with possibility. Overall, it led to a franchise that remains entertaining but underwhelming, if only because this first film in the trilogy sets the bar very high. Existing in a cyberpunk world where the imagination sets the limits of possibility, the film operates in languages ranging from computer code to kung-fu, offering a wide array of genres blended into this otherwise classical tale of good versus evil. And while continuously exalted by its fervent, jealously defending fans, the film seems smarter than it really is and, even while being smarter than the average actioner, has been propelled to impossibly high realms of greatness. Even though the Wachowskis never forget to engage the mind in their discussion about the nature of reality and humanity, which are then compressed into symbolic acts (such as swallowing a pill to demonstrate a belief), the film too often resorts to wistful gunplay and impressive, CGI-enhanced acrobatics, all of which viewers have seen before, though rarely better.

Shot for $44 million in Australia, the Wachowskis wrote The Matrix before their 1996 debut feature, the stylistic crime-thriller Bound. And in the wake of The Matrix’s franchise legacy, it’s interesting to think back to what must have inspired them in 1990s culture. To be sure, even while pointing toward the future, The Matrix also encapsulated much of the ’90s. By the middle of the decade, hopes for virtual reality technology were still very high, computer hackers were becoming more stylish than nerdy (see Hackers), and dark alternative music filled the radio waves (Marilyn Manson, Ministry, and Rage Against the Machine). As a result, the Wachowskis applied their unique vision to these elements and imagined a world where the human race’s savior is a hacker who hangs out at underground goth clubs. In 1999, nothing could be cooler. But more than just being the right movie at the right time, the Wachowskis also created a carefully assembled and highly stylized product, thanks in large part to the expert lensing by cinematographer Bill Pope, who also shot Bound. Every scene and sequence looks labored over, every shot carefully planned out, and the drab color palette beautifully composed. Because of the filmmakers’ tireless efforts, The Matrix‘s visual identity is almost mythic in a way its successors failed to achieve.

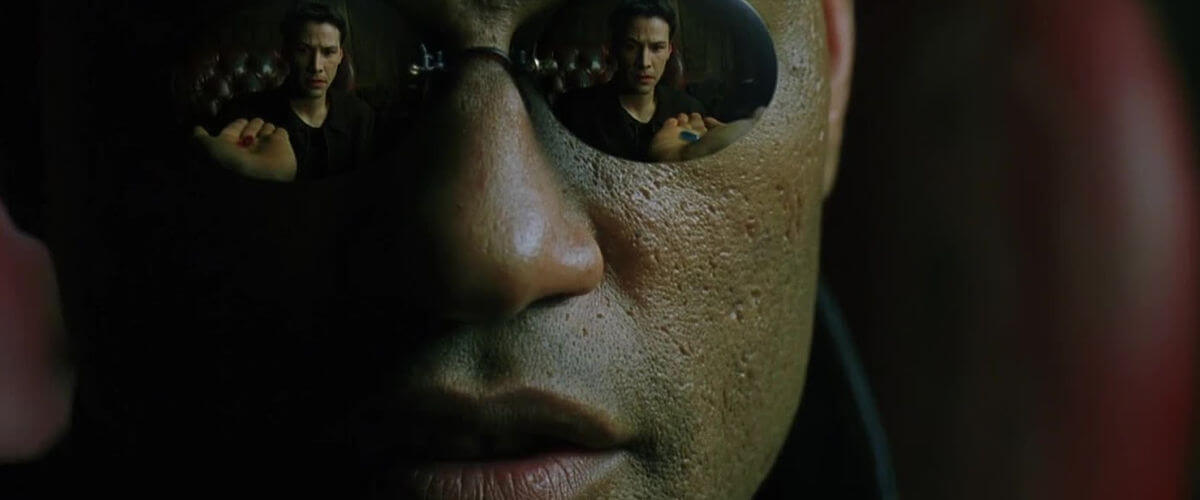

If you’ve been in a bubble and haven’t seen it, the film centers on Thomas Anderson (Keanu Reeves), who leads a double-life: an office worker by day, and by night, he’s a talented but restless hacker who goes by the handle “Neo.” Contacted by a group of wanted hackers, headed by Morpheus (Lawrence Fishburne) and Trinity (Carrie-Ann Moss), Neo learns that agents obsessed with finding Morpheus’ secret group are hunting him. The agents’ leader, the dastardly Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving), seems maniacally devoted to stopping Morpheus and all that he represents. Strangely, when he and Morpheus’ soldiers engage in combat, the action bends the laws of physics. Moreover, they use robotics that look like they come from far into the future (they do). Morpheus believes Neo is “The One” prophesied to save the real world, not Neo’s fabricated fantasy, from machine rule. Here is where the Wachowskis’ screenplay falls into long processions of expository dialogue between Morpheus and Neo, whereby Morpheus explains the way of the world to The One.

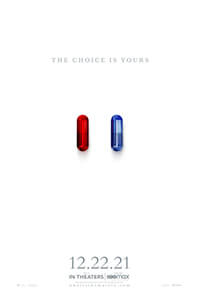

Rather than just tell him he’s been living in a computer-generated illusion, Morpheus talks in cryptic riddles and uses virtual reality visuals to illustrate his point. The short version is that machines have bred Neo and most other humans on the planet as a source of energy. Sometime in the 21st century, humans and machines went to war. The machines won and subjugated the human race. Born into embryotic pods, the human slaves never experience the dark truth of their reality; instead, the machines have constructed an intricate simulation called The Matrix. Human beings carry out their lives, never aware that they are essentially feeding their captors. But a rare few inside The Matrix search through computer codes and look for meaning. These hackers are eventually pulled out of The Matrix by others who have already escaped—a resistance based in an underground city called Zion. Morpheus explains that, long ago, someone prophesied the arrival of The One and through him the end of the war. Neo doubts Morpheus’ claims, and his misgivings only seem to be supported by Gloria Foster’s wise Oracle.

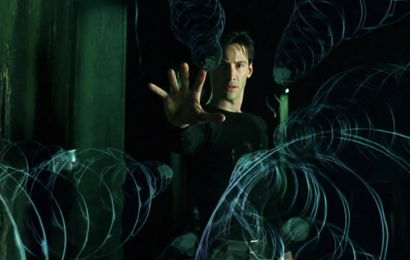

But Morpheus’ group, surviving on a magnetic ship in the post-apocalypse, has a traitor. Cypher (Joe Pantoliano) has sold Morpheus’ whereabouts to Agent Smith, so he’ll be allowed back into The Matrix with his knowledge of the real world erased forever (“Ignorance is bliss,” he explains). Once Agent Smith captures Morpheus, Neo and Trinity must lead a daring rescue mission, during which our hero discovers his prophesied abilities as The One: he can manipulate reality within the Matrix, allowing him to dodge bullets and leap great distances at will. Laden in black leather, sunglasses, and machine guns, the finale plays out in almost constant slow-motion, leading to our sense that greatness unfolds before us. But, before long, good trumps evil (at least, Agent Smith, not the more significant robot threat), and the rebels prevail. By the final scene, when Neo calls out to others in the Matrix who may be listening and then flies into the air like some comic book superhero, the Wachowskis’ visuals have created something iconic. The viewer cannot help but be swept away.

One of the lingering quibbles for this critic remains the underdeveloped love story between Neo and Trinity. It is, after all, a major dramatic factor in the film and a central plot point to Neo’s emergence as The One, as Trinity’s faith in him plays a crucial role in Neo becoming a messianic figure. She’s been told she will fall in love with The One, and she knows it’s Neo when she falls for him. But the Wachowskis offer audiences not a single scene that would help us understand why Trinity falls for him. The screenplay lacks any insight into her motivation beyond her hero-worship, while Neo understandably finds Moss appealing for superficial reasons. After all, Reeves isn’t an expert when it comes to emotive performances. Besides fighting for his survival in several thrilling action sequences, his character doesn’t do much beyond listening to Morpheus’ exposition about how the world is not as it seems. Trinity, too, is a tough cookie, but she’s one of many characters in the film who is two-dimensional at best. Curiously, the two most engaging, passionate characters are Morpheus in all his devotional certainty and Cypher, the duplicitous side-villain.

One of the lingering quibbles for this critic remains the underdeveloped love story between Neo and Trinity. It is, after all, a major dramatic factor in the film and a central plot point to Neo’s emergence as The One, as Trinity’s faith in him plays a crucial role in Neo becoming a messianic figure. She’s been told she will fall in love with The One, and she knows it’s Neo when she falls for him. But the Wachowskis offer audiences not a single scene that would help us understand why Trinity falls for him. The screenplay lacks any insight into her motivation beyond her hero-worship, while Neo understandably finds Moss appealing for superficial reasons. After all, Reeves isn’t an expert when it comes to emotive performances. Besides fighting for his survival in several thrilling action sequences, his character doesn’t do much beyond listening to Morpheus’ exposition about how the world is not as it seems. Trinity, too, is a tough cookie, but she’s one of many characters in the film who is two-dimensional at best. Curiously, the two most engaging, passionate characters are Morpheus in all his devotional certainty and Cypher, the duplicitous side-villain.

Of course, one could explain away my quibble with the film’s thematic underpinnings about Predestination vs. Determinism. Did Neo knock over the vase in the Oracle’s kitchen because she told him he would, or because it was his destiny to do so? Did Trinity fall in love with Neo because the Oracle prophesied she would, or because she genuinely fell in love with him? The Wachowskis embed a considerable amount of hypothesizing and philosophical waxing, all rooted in broad theory appropriate for an undergraduate Philosophy 101 course. Detractors have remarked about the fundamental nature of the literary, mystic, religious, and philosophical references throughout the film—that it’s trying to be smart but could have been a lot smarter—but remember, this is an action movie, first and foremost. A hint of philosophical insight automatically places it a step up from others like it. What the Wachowskis did with The Matrix is collectively raise expectations for actionized fare; such films no longer needed to be dim shoot-em-ups but could put some brainy concepts behind the action that would test John Q Moviegoer. Its considerable measure of hints and philosophical Easter eggs leave behind just enough for viewers to mull over. While its concepts may not be mind-blowingly original, they’re getting the average commercial action fan to think a bit more, which can only be a good thing. (Then again, a subculture of fans now believe they’re living in a computer simulation thanks to The Matrix.)

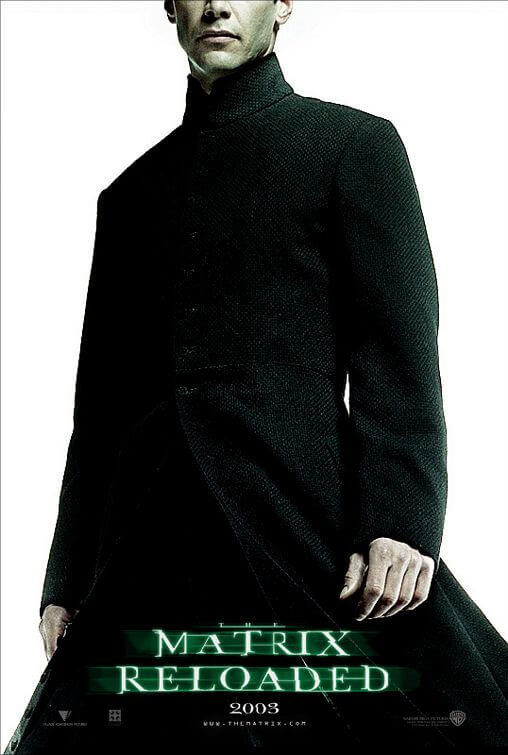

In terms of action, The Matrix never fails to entertain or inspire awe, from the CGI post-apocalyptic futureworld to the FX-enhanced fight sequences. Its eye-popping effects have been designed to deliver something new (in its day) and something that has a visual correlation to the story. Inside The Matrix, Neo can manipulate the laws of Nature and reality by freedom of thought. To illustrate this, visual effects supervisor John Gaeta famously employed “bullet-time” and hyper-slow-mo (a technique invented some years prior and notably used the previous year on the Lost in Space feature). The result allows characters to dodge blows and bullets, leap incredible distances, and melt reality as we know it. Countless action movies and martial arts fare have borrowed these visuals, so, for better or worse, we’ve been following slow-mo bullets and spinning around action heroes stuck in a freeze-frame ever since The Matrix‘s release. What’s more, once Neo realizes the full extent of his powers, he becomes a kind of superhero with telekinetic abilities whose limits are never completely defined. The ambiguous promise held by Neo’s skills and how they might manifest onscreen culminate in the conclusion of The Matrix’s indescribably exciting last shot. If only the sequels lived up to that promise.

In terms of action, The Matrix never fails to entertain or inspire awe, from the CGI post-apocalyptic futureworld to the FX-enhanced fight sequences. Its eye-popping effects have been designed to deliver something new (in its day) and something that has a visual correlation to the story. Inside The Matrix, Neo can manipulate the laws of Nature and reality by freedom of thought. To illustrate this, visual effects supervisor John Gaeta famously employed “bullet-time” and hyper-slow-mo (a technique invented some years prior and notably used the previous year on the Lost in Space feature). The result allows characters to dodge blows and bullets, leap incredible distances, and melt reality as we know it. Countless action movies and martial arts fare have borrowed these visuals, so, for better or worse, we’ve been following slow-mo bullets and spinning around action heroes stuck in a freeze-frame ever since The Matrix‘s release. What’s more, once Neo realizes the full extent of his powers, he becomes a kind of superhero with telekinetic abilities whose limits are never completely defined. The ambiguous promise held by Neo’s skills and how they might manifest onscreen culminate in the conclusion of The Matrix’s indescribably exciting last shot. If only the sequels lived up to that promise.

Benefited by a sense of discovery that its subsequent two entries lack, The Matrix challenges viewers to consider their world as a construct of virtual reality that can be broken down and controlled through the power of thought. At the time, audiences responded with wild enthusiasm, creating a sort of cult-of-The Matrix that boasted over the film’s originality, despite many similar themes and twists being present in Alex Proyas’ Dark City the year before, and many other films like it. But the initial film’s legacy carries beyond its subsequent entries and, as a stand-alone, remains a thrilling and visionary piece of innovation. Perhaps overestimated, but compelling and visionary, few pure action movies have dared to be so much and succeeded so thoroughly in making general audiences think about the world around them and how they perceive it. By remaining so accessible yet thoughtful, The Matrix transcends its narrative downfalls through its influence and insight—characteristics that continue to define the Wachowskis’ unique brand of ambitious entertainment.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review