The Master

By Brian Eggert |

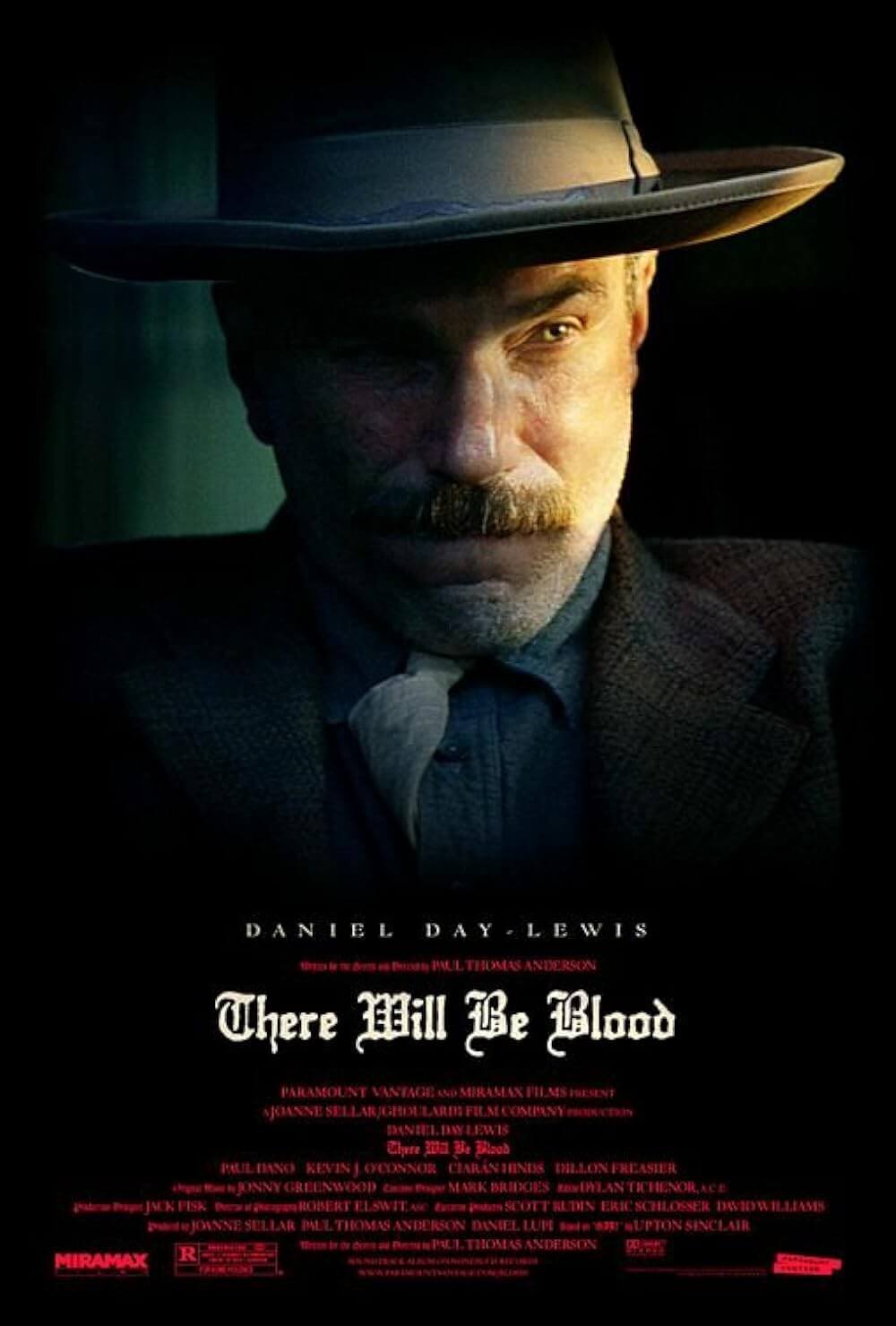

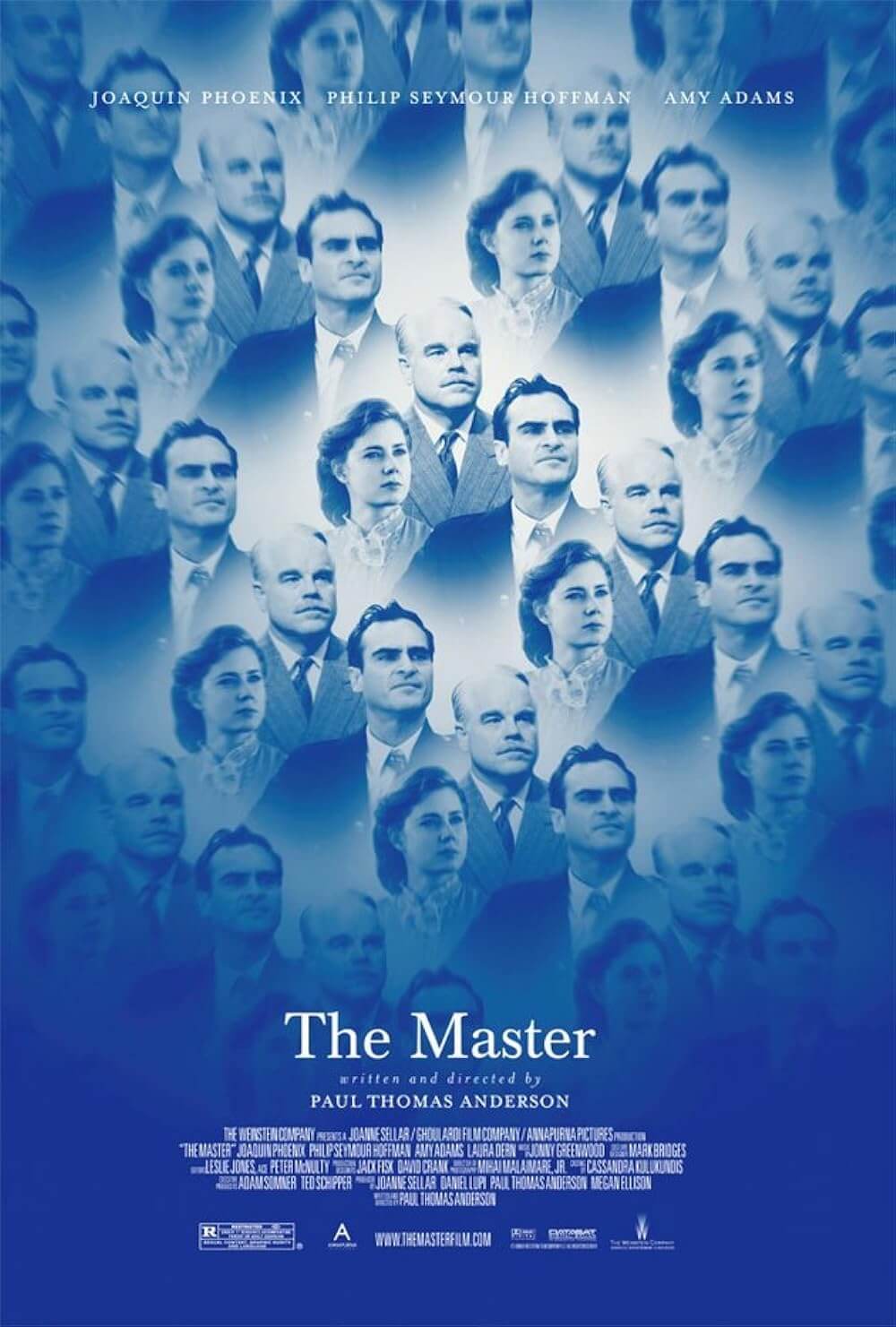

Meditative about its themes, Paul Thomas Anderson’s The Master does not lead to an overarching epiphany but demands persistent investigation throughout and long afterward to determine what it has to say about religion and mankind’s omnipresent need to fill the emptiness of belief. The film is not, as some have anticipated, a cathartic muckraking exposé on The Church of Scientology; instead, it uses Scientology as a metaphor for the maddening command of faith and illusion of control powering every religion. Akin to Anderson’s masterpiece There Will Be Blood from 2007, this portrait of America cuts deep, its blows concealed by the guise of bold filmmaking and unconventional narrative, further amplified by Anderson’s majestic treatment and profound character depth, the centerpiece of which are performances by Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman. For all its grandiosity, the film’s turns will no doubt confound general audiences; nevertheless, every frame reverberates with the call of an important work of art that remains a challenge to encapsulate.

As the film opens, aptly named Freddie Quell (Phoenix), a World War II sailor with a volatile look of unrest behind his eyes, writhes in his skin when the war ends. On a Pacific beach, during a celebration with his fellow sailors, the men shape a female figure out of sand; Freddie clownishly pantomimes copulation to everyone’s delight, and then goes off to masturbate into the ocean. He and others are told their post-traumatic stress disorder may result in uneasy integration back into society; none more so than Freddie, whose face is crooked, cracked and contorted in Phoenix’s uncanny portrayal, as though all signs of civilization have been scraped off by the war. A series of mental exams follow Freddie’s stay in a Navy hospital; he responds to Rorschach inkblots by seeing all manner of genitalia and chuckling about it. Much like the opening shot of ocean water churning in the wake of a ship—an important visual that appears later in the film as well—Freddie is in flux, erratic and childlike, and bound to an inarticulate frenzy ever numbed, or perhaps augmented, when he mixes cocktails with everything from photographic chemicals to torpedo engine fuel. He is the unadulterated human beast that must be suppressed.

Soon Freddie finds himself a job taking portrait photos in a department store where, after sleeping with a model and battling a customer in a startling outburst, he runs off to find work in a cabbage field. One of his rancid concoctions accidentally kills a laborer, so Freddie runs again and stumbles onto a ship at a port in San Francisco and seemingly owned—but actually borrowed, as we learn later—by Lancaster Dodd (Hoffman), who introduces himself by saying, “I am a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist, a theoretical philosopher. But above all, I am a man. A hopelessly inquisitive man. Just like you.” Finding this evidently unbalanced stowaway on his boat, Dodd responds with curious acceptance and even asks that Freddie devise one of his special potions for him. In Freddie, Dodd sees something special, the possibility for a subject of experimentation for The Cause, his own cultish pseudo-religion of part science, part mysticism, and for which Anderson was in no small way inspired by Scientology. Dodd maintains that “man is not an animal,” and Freddie represents the decisive trial in which to prove his theory. Now consider Dodd’s conflicting choice of words when he tells Freddie, “You will be my guinea pig and protégé.”

Soon Freddie finds himself a job taking portrait photos in a department store where, after sleeping with a model and battling a customer in a startling outburst, he runs off to find work in a cabbage field. One of his rancid concoctions accidentally kills a laborer, so Freddie runs again and stumbles onto a ship at a port in San Francisco and seemingly owned—but actually borrowed, as we learn later—by Lancaster Dodd (Hoffman), who introduces himself by saying, “I am a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist, a theoretical philosopher. But above all, I am a man. A hopelessly inquisitive man. Just like you.” Finding this evidently unbalanced stowaway on his boat, Dodd responds with curious acceptance and even asks that Freddie devise one of his special potions for him. In Freddie, Dodd sees something special, the possibility for a subject of experimentation for The Cause, his own cultish pseudo-religion of part science, part mysticism, and for which Anderson was in no small way inspired by Scientology. Dodd maintains that “man is not an animal,” and Freddie represents the decisive trial in which to prove his theory. Now consider Dodd’s conflicting choice of words when he tells Freddie, “You will be my guinea pig and protégé.”

But, as suggested, the first and greatest misconception about The Master is that Anderson tells the story of Scientology. Of course, Dodd and Scientology creator L. Ron Hubbard bear many similarities, the latter having conceived Dianetics and the precepts of Scientology in the 1950s. The Cause and Scientology do function on many of the same grounds. Early on, Freddie undergoes psychological “processing” where, in a method akin to Scientology’s “auditing,” the subject’s past lives are explored to overcome the lingering trauma they may have endured in another life. He’s forced to answer a series of questions without blinking: “Do your past failures bother you?” or “Have you ever had sex with a family member?” Never mind why he shouldn’t blink—Freddie responds through laughter and discomfort, but he wants to pass Dodd’s test, whatever the purpose may be. The exercise seems hopeless until there’s a breakthrough when he recollects his lovelorn interlude with a teenage girl from his past. Anderson’s camera is achingly close in these scenes, the actors and emotions huge on the screen before us.

Under Dodd, who’s almost always referred to as “master,” The Cause operates somewhere between Freudian psychotherapy, hypnosis, and parlor trickery. Like a dog, Freddie follows without question and without much thought, wasted and only half-present most of the time. Perhaps it’s because The Cause’s strictures are so vague that Freddie has no precise rules to question. When Dodd’s methods are challenged by a guest at a New York City dinner party, The Master responds with aggressive disdain. He will not be doubted by dissenters. By this time, Freddie has become Dodd’s loyal hound and attacks the skeptic at his home that evening. Indeed, Dodd has a devoted group of followers: His wife and resolute deputy Peggy (Amy Adams), his daughter Elizabeth (Ambyr Childers), his son-in-law Clark (Rami Malek), and countless friends follow Dodd’s writings, convinced The Cause will end war, heal “certain forms of leukemia,” and open up their consciousness to humanity’s trillion (with a “T”) year history. Dodd’s son Val (Jesse Plemons) seems to be the only person near him who understands, “He’s making all this up as he goes along”.

Comparable to Daniel Plainview, the Oscar-winning role of Daniel Day-Lewis in There Will Be Blood, Anderson explores another megalomaniacal personality in Lancaster Dodd, whose pomposity is curbed by his faux humility amid the vastness of the universe as he sees it. A dogged authoritarian, he presents himself with good-humored stories, bawdy songs, and an outwardly jovial manner. He wants to be worshiped without any hint of doubt, and disbelievers are treated with irate bursts of intolerance. Val is right, though—Dodd is making everything up as he goes. He never diagnoses Freddie, except to say his animalistic nature must be contained. So many of Dodd’s examinations involve a free-form application of limitations on Freddie, who resists participating compliantly at first, and then desperately attempts to conform in his way (he remains incapable of giving up the drink). Dodd takes him to the breaking point and creates the illusion of a breakthrough, but what in any of these cases has been accomplished? Nothing except a demonstration of his own dominance. In one sequence, he forces Freddie to walk back and forth in a foyer as followers watch; Freddie must touch a wooden wall and then a window on the other side of the room, back and forth, for hours, days, weeks it seems. When it’s all over, the two men hug, and Freddie feels he has passed. But what has been accomplished? Dodd admits he doesn’t know.

Comparable to Daniel Plainview, the Oscar-winning role of Daniel Day-Lewis in There Will Be Blood, Anderson explores another megalomaniacal personality in Lancaster Dodd, whose pomposity is curbed by his faux humility amid the vastness of the universe as he sees it. A dogged authoritarian, he presents himself with good-humored stories, bawdy songs, and an outwardly jovial manner. He wants to be worshiped without any hint of doubt, and disbelievers are treated with irate bursts of intolerance. Val is right, though—Dodd is making everything up as he goes. He never diagnoses Freddie, except to say his animalistic nature must be contained. So many of Dodd’s examinations involve a free-form application of limitations on Freddie, who resists participating compliantly at first, and then desperately attempts to conform in his way (he remains incapable of giving up the drink). Dodd takes him to the breaking point and creates the illusion of a breakthrough, but what in any of these cases has been accomplished? Nothing except a demonstration of his own dominance. In one sequence, he forces Freddie to walk back and forth in a foyer as followers watch; Freddie must touch a wooden wall and then a window on the other side of the room, back and forth, for hours, days, weeks it seems. When it’s all over, the two men hug, and Freddie feels he has passed. But what has been accomplished? Dodd admits he doesn’t know.

Nevertheless, Dodd’s authority demands nothing short of absolute obedience, and his control can only be exercised on those who will be controlled. Later in the film, Laura Dern’s follower and contributor Helen Sullivan questions Dodd’s new views published in his second book, which suggests instead of remembering past lives, they “imagine” them; rather than provide an explanation, he spurns her for questioning his doctrine. In this sense, The Master is not, as the title suggests, and about one man, but rather the relationship between two types of people, those with a desire to control others and those who desire to be free of control. As the film progresses and the relationship continues with the Master testing his guinea pig over and over, in time, we realize these are two halves of the same whole—yin and yang, order and chaos, acolyte and teacher, conman and patsy, huckster and shill, unrepentant masculinity and the gentleman pretense, pet and owner. Freddie farts and then laughs about it; Dodd just smiles and calls him a “Silly animal.” In Freudian terms, they are id and superego. But Dodd also admires Freddie because he sees that which The Cause seeks to expel, the basic animal drives written into our DNA that Dodd himself must deny. The film’s final swan song implies Dodd may even envy Freddie’s lack of inhibition. Meanwhile, Peggy, the hardened power behind the throne, represents the ego that attempts to stabilize the id and superego pairing. As the prototypical 1950s wife, she must control Dodd’s manifest animal drives. One scene shows her gratifying her husband in the washroom as if tightening a pesky loose screw.

To be sure, in the end, Dodd needs Freddie more than the reverse, resulting in a profound commentary on how religious shepherds require sheep; otherwise, they’re just fanatics preaching to themselves. The more sheep, the more merit that is placed on their words. Except, as we see in Dodd’s Salt Flats motorcycle experiment where The Master picks a point and rides to it, when it’s Freddie’s turn, he just rides off into an anti-climactic disappearance, having seen through Dodd’s charade. He would choose to stay if The Cause would have him, if only for a feeling of acceptance; although, unlike many other religions, this cult demands unquestionable conformity, and Freddie cannot stop being an animal. But he’s content on his own just the same. Herein resides Anderson’s broad-in-scope anti-religious themes, just under the surface where god-fearing American audiences may not see them. His depiction of religion, just as it was in There Will Be Blood with Paul Dano’s charlatan and zealot Eli Sunday, takes the form of a duplicitous figurehead in whom all revelations are false. The character is so distinct and larger-than-life that audiences might overlook the film’s commentary in favor of the power behind the storytelling.

If Anderson began his career emulating masters like David Mamet, Martin Scorsese, and Robert Altman, with There Will Be Blood and now The Master the director evokes the elusive majesty of Stanley Kubrick. Every frame here contains textures and compositions that deserve to be frozen and displayed as individual pieces of art. Mihai Malaimare’s cinematography, presented in 70mm (the first film in this format since Ron Howard’s Far and Away in 1992), heightens our senses in every mammoth composition and lovingly perfected detail. The 1950s production design by David Crank and Jack Fisk and costumes by Mark Bridges appear to have arrived onscreen by time travel they’re so convincing. The score by Jonny Greenwood, who also created the music for There Will Be Blood, brings another series of haunting, winding, and relentless sections of music that make us feel we’ve stepped into a dream. In fact, much like Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, some moments in the film feel as though Anderson has bled from the margins of reality and dripped into some lurid fantasy. During a Cause party, Dodd sings a jaunty tune to a roomful of delighted guests, while Freddie imagines all the women without clothes. But is it just his imagination that these women hop about nude? Anderson walks the line between reality and dream throughout the picture with absolute control over his ambiguity, demonstrating an unfathomable degree of genius in his ability to intrigue and yet delay our total comprehension.

If Anderson began his career emulating masters like David Mamet, Martin Scorsese, and Robert Altman, with There Will Be Blood and now The Master the director evokes the elusive majesty of Stanley Kubrick. Every frame here contains textures and compositions that deserve to be frozen and displayed as individual pieces of art. Mihai Malaimare’s cinematography, presented in 70mm (the first film in this format since Ron Howard’s Far and Away in 1992), heightens our senses in every mammoth composition and lovingly perfected detail. The 1950s production design by David Crank and Jack Fisk and costumes by Mark Bridges appear to have arrived onscreen by time travel they’re so convincing. The score by Jonny Greenwood, who also created the music for There Will Be Blood, brings another series of haunting, winding, and relentless sections of music that make us feel we’ve stepped into a dream. In fact, much like Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, some moments in the film feel as though Anderson has bled from the margins of reality and dripped into some lurid fantasy. During a Cause party, Dodd sings a jaunty tune to a roomful of delighted guests, while Freddie imagines all the women without clothes. But is it just his imagination that these women hop about nude? Anderson walks the line between reality and dream throughout the picture with absolute control over his ambiguity, demonstrating an unfathomable degree of genius in his ability to intrigue and yet delay our total comprehension.

We can at least be certain that Anderson has supplied moviegoers with possibly the two best performances in recent memory. Phoenix and Hoffman, who competed in 2005 for the Academy Award for Best Actor in their respective Walk the Line and Capote (Hoffman won) performances, will surely be competing against each other again. Phoenix is less a performance than a sheer embodiment. At times, we cringe at the level of commitment exhibited; the actor wrestles three policemen to the ground and later crashes his body against a prison cell bunk, and all of it looks painful. But then, so does keeping that fractured expression on his face. In Phoenix’s eyes, Freddie’s unhinged nature burns with an otherness that makes us see him as Dodd does, as a base creature impossible to grasp or control, but also carrying a pain embedded incomprehensibly deep. Phoenix is wonderfully unpredictable, whereas by contrast, Hoffman must feel shrewd and deliberate, following their id and superego design. Hoffman is at his best when playing these impossibly large characters, and this is perhaps his biggest role yet in terms of his character’s outward identity and portentous personality. When the two performers are together in the frame, at times, we can only sit back in awe of the caliber of acting before us.

A film that defies complete understanding as it commands our fascination, finally The Master is a complicated tale and a beautifully made motion picture. Although perhaps not as obviously and viscerally scathing as There Will Be Blood (the director’s magnum opus), the film is some kind of masterpiece. There are moments where the visual textures and unbelievable performances leave us to percolate in Anderson’s world, and for that instant, we forget all else as sweeping camera movements pull us along, and Greenwood’s score sends goosebumps down our arms. To compare the richness of the filmmaking to another Kubrick film, it reminds one of Barry Lyndon, where the intentional pacing and elusive characters require much digestion and even several viewings to completely fathom and appreciate, while the splendors of the production itself do their part to constantly distract us from its greater meaning. And like that film, this one will grow with time, as Anderson does not engage a straightforward exploration of his picture’s themes but rather a contemplation of them that leads us to question what we’ve seen and what it suggests. Films such as this cannot be dismissed. They demand to be seen again and again until we figure them out, if such a thing is possible.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

As the season turns toward gratitude, I’m reminded how fortunate I am to have readers who return week after week to engage with Deep Focus Review’s independent film criticism. When in-depth writing about cinema grows rarer each year, your time and attention mean more than ever.

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your moviegoing—whether it’s context, insight, or simply a deeper appreciation of the art form—I invite you to consider supporting it. Your contributions help sustain the reviews and essays you read here, and they keep this space independent.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review