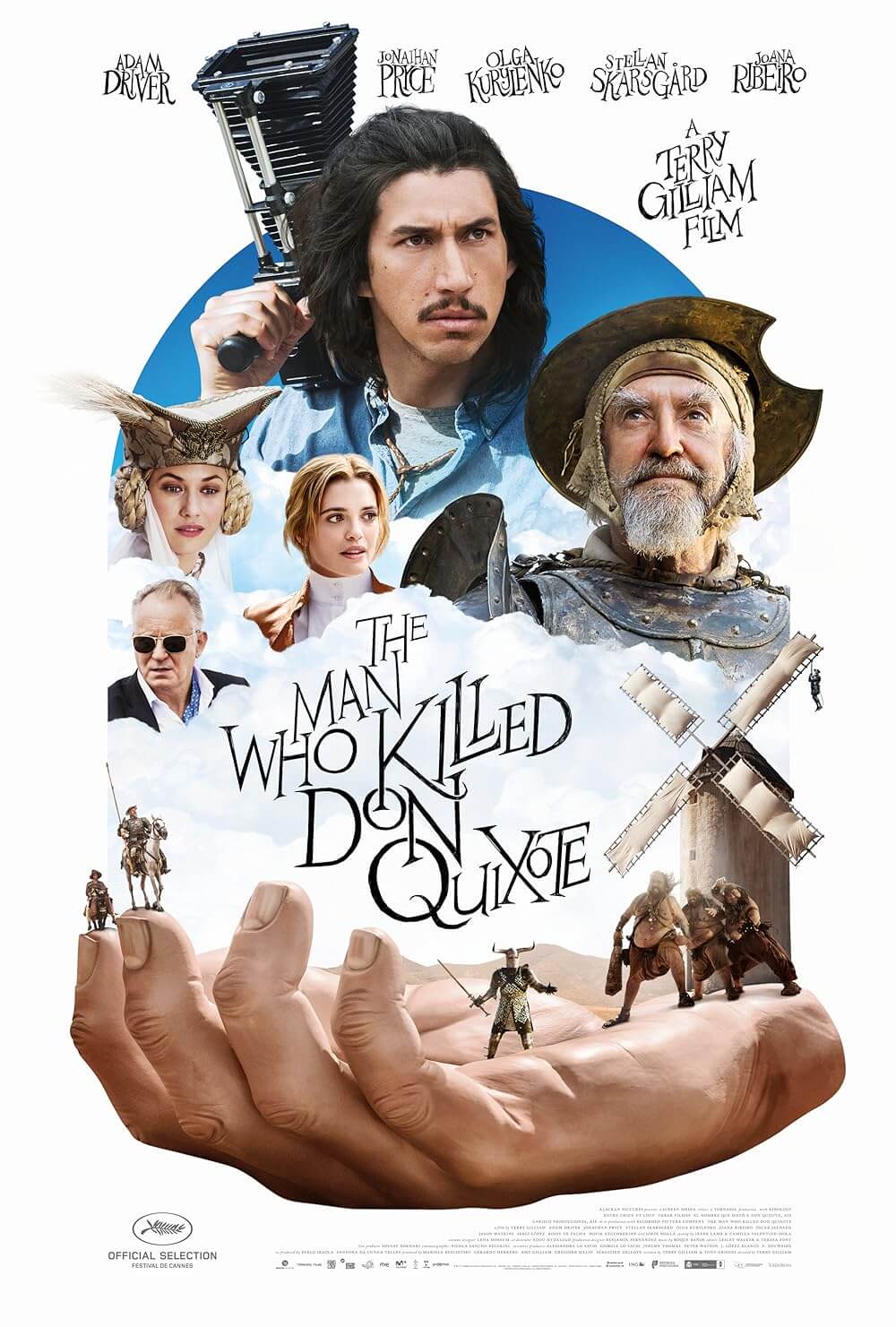

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote

By Brian Eggert |

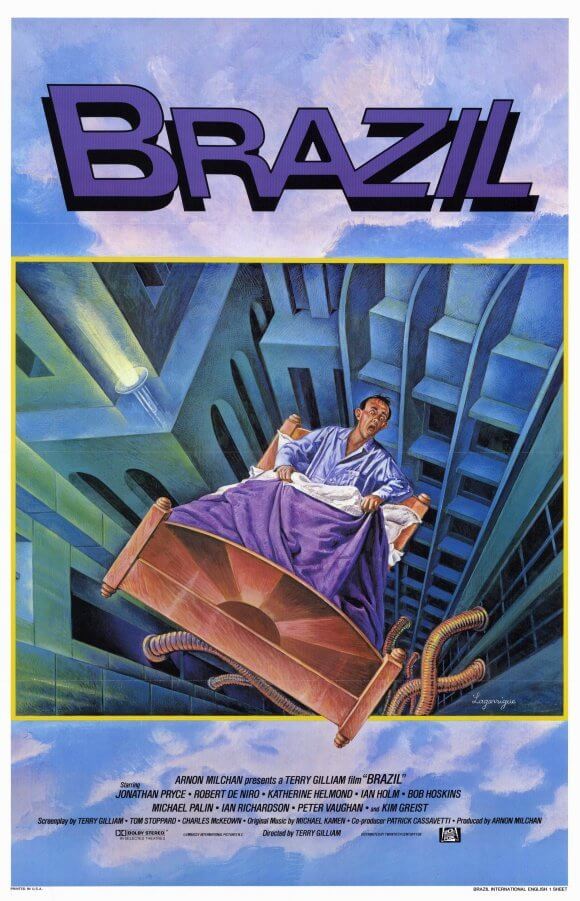

Nearly every Terry Gilliam project has been cursed in some manner. Each has an irresistible production story that risks overshadowing the eventual film. Sometimes the surviving film transcends the troubled process of its creation, drawing fascinating parallels between life and art. Such is the case with the near-calamitous fight for Brazil in 1985, which represented a rare victory for Gilliam when his masterpiece was released in all its cynical glory, without the happy ending demanded by worried studio bosses. Other times, the behind-the-scenes drama transforms the end product into more of a case study than a watchable film. When you try to sit through Gilliam’s 2005 release The Brothers Grimm, you can feel the misguided influence of the Weinsteins from scene to scene. Whether these stories of cursed productions lead to a lesson about an off-the-rails filmmaker or the dangers of studio interference is open to interpretation. But film after film, Gilliam either thrives or falls victim to his chaotic productions, and many of his critics question whether he’s the author of these situations. As he remarked about filmmaking in the 2002 documentary Lost in La Mancha, following his first abortive attempt to shoot The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, “Without a battle, maybe I don’t know how exactly to approach it.”

Few tales of behind-the-scenes woe can compare to those preceding Gilliam’s long-awaited completion of The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. Only the tragic production histories of Orson Welles compare. But similar to last year’s impossibly overdue release of Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind, Gilliam achieves his own unlikely and qualified victory here. Both films fall into a strange category of sloppy and unsatisfying works of genius, instant films maudit that will take more than a single viewing to process and deconstruct. Gilliam’s film debuted in May 2018 at the Cannes Film Festival, two decades to the month after the director announced it as his next project following the release of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), and almost three decades after he first started to develop an adaptation of Miguel de Cervantes’ essential 1605 book—a post-modern text before modernist concepts were established in literature. However, when filmmakers finally realize their dream projects after decades of development, sometimes they have spent so many years making, talking about, and rethinking the production in their head that the end result cannot help but disappoint or feel overworked. One feels compelled to approach The Man Who Killed Don Quixote with the same caution required to watch Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York (2002) or Oliver Stone’s Alexander (2004).

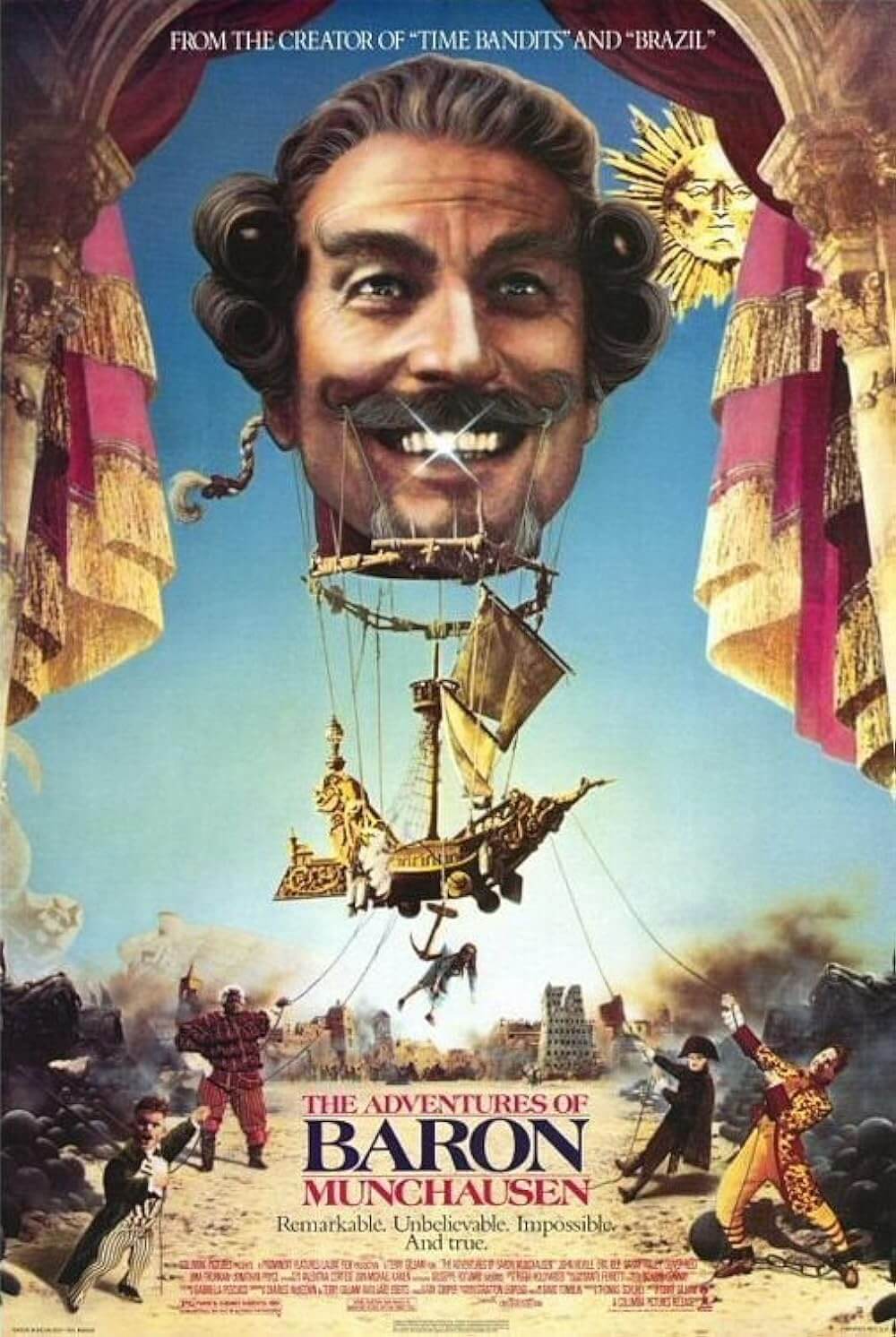

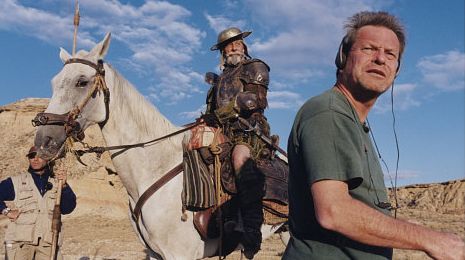

In the three decades between Gilliam settling on Cervantes and the release of his film, he went through several iterations, false starts, litigious relationships with producing partners, recastings, canceled productions, and dramatic rewrites. He spoke at Cannes in 2016 about the protracted production length, describing it as “one of those dream nightmares that never leave you until you finish the thing.” Of course, making a comparison between Gilliam and Quixote is irresistible, and perhaps entirely unavoidable. Cervantes’ hero is the perfect metaphor for Gilliam and his production, if not many of the director’s other troubled productions as well, including Brazil and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988). Quixote is, after all, a symbolic figure of the lost cause, whose very name inspired quixotic, an adjective synonymous with impracticality and unrealistic ambition. This is the essence of Gilliam, cinema’s patron saint of imagination and dreamers, whose frantic but inspired artistic demands can damage a delicate production schedule, and sometimes result in chaos. Documentarians Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe captured this quality of Gilliam’s work in their 1996 feature The Hamster Factor, detailing the making of 12 Monkeys—its title a reference to how the filmmaker spent hours of valuable production time to get a hamster, placed in the background of an already busy scene, to run in its wheel.

Gilliam’s first attempt at the production went before cameras in 2000; even then, the director had been through a decade of false starts and delays. His original concept for The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, co-written with Tony Grisoni, blended ideas from Cervantes’ novel and Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court from 1899. Both original stories involve a complex assessment of chivalry, at once mourning its loss and satirizing its more absurd conventions. Gilliam’s was far from a traditional take on Quixote, the crazed nobleman who, after imagining himself as a knight in one of his romantic adventure novels, dresses in makeshift armor, recruits peasant farmer Sancho Panza as his squire, and sets out to bring chivalry to the modern world. Johnny Depp was set to star as an executive who travels back in time to meet Quixote, played by French actor John Rochefort. But early on, the production went out of control. In the first week of filming, jets from a nearby NATO base flew overhead and made it impossible to capture sound. A freak storm caused flooding that damaged expensive equipment, and the production’s insurance refused to cover the losses. A few days later, Rochefort found himself in incredible pain and, before long, his doctors diagnosed him with two herniated discs, and the actor could not continue. Inevitably, the string of disasters resulted in the production’s cancellation; worse, the insurance company acquired ownership of the script, meaning Gilliam would have to buy back his own project.

Gilliam’s first attempt at the production went before cameras in 2000; even then, the director had been through a decade of false starts and delays. His original concept for The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, co-written with Tony Grisoni, blended ideas from Cervantes’ novel and Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court from 1899. Both original stories involve a complex assessment of chivalry, at once mourning its loss and satirizing its more absurd conventions. Gilliam’s was far from a traditional take on Quixote, the crazed nobleman who, after imagining himself as a knight in one of his romantic adventure novels, dresses in makeshift armor, recruits peasant farmer Sancho Panza as his squire, and sets out to bring chivalry to the modern world. Johnny Depp was set to star as an executive who travels back in time to meet Quixote, played by French actor John Rochefort. But early on, the production went out of control. In the first week of filming, jets from a nearby NATO base flew overhead and made it impossible to capture sound. A freak storm caused flooding that damaged expensive equipment, and the production’s insurance refused to cover the losses. A few days later, Rochefort found himself in incredible pain and, before long, his doctors diagnosed him with two herniated discs, and the actor could not continue. Inevitably, the string of disasters resulted in the production’s cancellation; worse, the insurance company acquired ownership of the script, meaning Gilliam would have to buy back his own project.

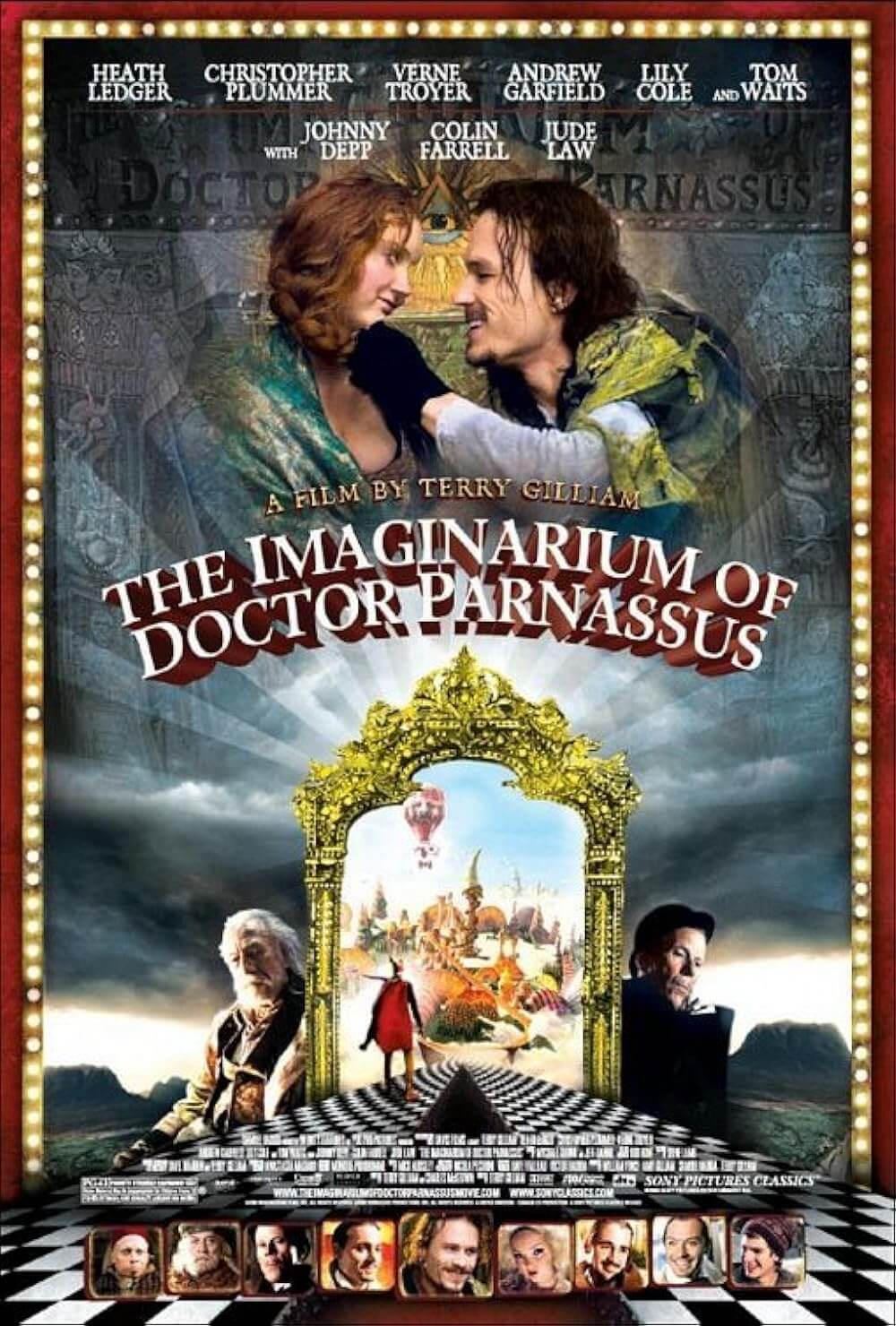

It might all seem like an impossibly horrible streak of bad luck, but documentarians Fulton and Pepe followed Gilliam’s progress, or lack thereof, from behind the scenes, and this grievous first attempt resulted in the extraordinary and depressing Lost in LaMancha (2002). Over the years, the troubles continued as Gilliam made gradual progress on another attempt at The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. He regained the rights to the screenplay, recast Quixote with a series of actors (Robert Duvall, John Hurt, Michael Palin), and recast the Depp role (Ewan McGregor, Jack O’Connell). Meanwhile, he completed the divisive Tideland (2005) without descending into cataclysm; The Brothers Grimm (2005), which resulted in a minor disaster after the director clashed with the Weinsteins; The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009), a production barely salvaged after the death of its star, Heath Ledger; and the stellar, if underseen The Zero Theorem (2014), which made it to the screen without incident, comparatively speaking. Around this time, Spanish financier and would-be producer Paulo Branco offered to put up the funds for a new iteration of The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. But Branco made unreasonable demands on the budget, including a drastic cut of castmember wages. Gilliam refused to work with Branco and made arrangements with other investors, and their arrangement led to a completed film. But Gilliam’s severed relationship with Branco incited a legal battle once the new production wrapped, causing problems with the film’s distribution, particularly in the United States. Even so, the hard-won, finished version of The Man Who Killed Don Quixote reached most of the world, and it’s something of a miracle that the film exists at all after this long and painful backstory.

After following Gilliam’s ups and downs in trade reports for years, it’s almost impossible to set aside those aching details and consider what Gilliam has made without assigning everything onscreen autobiographical relevance. But perhaps we’re not supposed to. From the first scene onward, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote rings with metatextuality, as several characters look and sound like key players on Gilliam’s canceled 2000 shoot, a palpable reference point. The film opens on a commercial shoot in Spain, where frustrated director Toby (Adam Driver), a composite of Gilliam and Grisoni, tries to complete a project that isn’t going his way. The brief moments of footage mirror how Gilliam wanted to start his earlier iteration—where Don Quixote misidentifies a windmill as a giant, and upon charging the perceived ogre with a sword, he’s caught in one of the fans and thrown onto his back. As the new film progresses, we also notice a bohemian peddler with long black hair and a single blonde streak who resembles Depp’s appearance in the discarded footage from two decades ago. We suspect the Australian-accented first assistant director nods to the earlier production’s Philip A. Patterson. And we cannot ignore the way Toby, much like Gilliam, balks at the use of CGI over (im)practical models. Indeed, Gilliam’s new film has been reworked into a commentary on the famously abandoned version.

To complete his commercial, Toby hopes to find two local actors—Javier (Jonathan Pryce), an elderly shoemaker, and Angelica (Joana Ribeiro), an ingénue—he used in a student film he made about Don Quixote some ten years earlier. Flashbacks to the arty black-and-white student production show Toby trying to convince Javier to believe he is Quixote. And when Toby finds him, it seems that in the interim Javier has committed to his character. He inhabits a sideshow on the outskirts of town, convinced he is the Don Quixote. Upon seeing Toby, this crazed, costumed old man believes the young director is Sancho Panza. Aware that Javier has a few “squirrels in the attic,” Toby tries to avoid the man, but their fates are inextricably linked. An encounter with the authorities sends them on the run together in the desertous Spanish countryside, and they set out to rescue the fair maiden Angelica, who has fallen into a debaucherous life of sexual servitude to a cruel Russian businessman, Alexei (Jordi Mollà). However, Toby’s boss (Stellan Skarsgård) forbids him from upsetting Alexei, as he’s their new client.

To complete his commercial, Toby hopes to find two local actors—Javier (Jonathan Pryce), an elderly shoemaker, and Angelica (Joana Ribeiro), an ingénue—he used in a student film he made about Don Quixote some ten years earlier. Flashbacks to the arty black-and-white student production show Toby trying to convince Javier to believe he is Quixote. And when Toby finds him, it seems that in the interim Javier has committed to his character. He inhabits a sideshow on the outskirts of town, convinced he is the Don Quixote. Upon seeing Toby, this crazed, costumed old man believes the young director is Sancho Panza. Aware that Javier has a few “squirrels in the attic,” Toby tries to avoid the man, but their fates are inextricably linked. An encounter with the authorities sends them on the run together in the desertous Spanish countryside, and they set out to rescue the fair maiden Angelica, who has fallen into a debaucherous life of sexual servitude to a cruel Russian businessman, Alexei (Jordi Mollà). However, Toby’s boss (Stellan Skarsgård) forbids him from upsetting Alexei, as he’s their new client.

If the plot reads as messy, and the film plays as somewhat turbulent, even deranged, then you know you’re in Gilliam country. His films often tell stories that leap headlong and at random from one sequence to the next, with an unconventional logic from scene to scene. The tones shift from adventurous to irreverent to romantic to grotesque in an instant. But somehow, the whole experience congeals into a wonderful whole. Through the chaotic interactions between Toby and Quixote, the former begins to teeter-totter between reality and fantasy, resulting in bizarre digressions, asides, and slips into illusion more suited to the latter. One sequence takes Toby back in time to the Inquisition where he learns a harsh lesson about the Catholic persecution of Muslims in Spain. Another finds him French kissing a sheep. All the while, Driver has a manic intensity without sacrificing the audience’s sympathy for the character. And Pryce plays his role beautifully, with notes ranging from absurdist humor to the ache of an insane man who realizes, tragically, that his reality as a knight is nothing more than a fantasy.

Of course, The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is an excellent looking film. Gilliam’s imagination—combined with Nicola Pecorini, his cinematographer since Tideland, and the production design by Benjamín Fernández—conceives of countless beautiful shots, mostly captured on location in historic Spanish buildings or along the countryside. Gilliam also never ceases to find a compelling visual perspective. While early scenes look relatively normal by Gilliam’s standards, he avoids his usual wide-angle lenses or cockeyed angles in favor of simple juxtapositions, such as when modern wind turbines and windmill set-pieces inhabit the same shot. But the film becomes progressively more immersed in carnivalesque imagery as it goes, and most of the expressive formal tricks are reserved for Toby’s student film, or the later scenes when Toby begins to hallucinate and feel increasingly displaced by his surroundings. Gilliam’s camera is always moving, and his restless imagination has a trillion ideas to show us, even if the viewer’s eyes and mind cannot hope to process everything in a single sitting. Still, his relationship with computer-generated images has been uneasy at best (see The Brothers Grimm), and two scenes feature distractingly poor CGI.

A few cheap special FX and a third act that carries on too long are easy enough to overlook for the sheer energy and autobiographical filmmaking on display. If ever a director deserved to engage in self-referential imagery, it’s Gilliam with The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, and he does so without distracting from the forward momentum of the film itself. Viewers literate in the director’s films will note a religious procession similar to one in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975). A scene late in the film finds Pryce’s Quixote on a wooden horse and imagines him on a trip to the moon, a notion that evokes The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. And the entire concept of the screen story brings to mind The Fisher King (1992), as both involve a rational, albeit acerbic talent who finds his humanity, along with his grasp on reality, tested when he takes sympathy on a destitute and delusional companion. The film is not merely self-referential, but also self-critical on Gilliam’s part. With Toby a stand-in for the director, Gilliam is not beyond acknowledging his own downfalls by way of the character. Toby can be cruel, narrow-minded, chauvinistic, and impulsive—he leaves the set of his commercial behaving “like a fucking child,” says one of his crew, recalling the way many on Gilliam’s 2000 production questioned his professionalism.

A few cheap special FX and a third act that carries on too long are easy enough to overlook for the sheer energy and autobiographical filmmaking on display. If ever a director deserved to engage in self-referential imagery, it’s Gilliam with The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, and he does so without distracting from the forward momentum of the film itself. Viewers literate in the director’s films will note a religious procession similar to one in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975). A scene late in the film finds Pryce’s Quixote on a wooden horse and imagines him on a trip to the moon, a notion that evokes The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. And the entire concept of the screen story brings to mind The Fisher King (1992), as both involve a rational, albeit acerbic talent who finds his humanity, along with his grasp on reality, tested when he takes sympathy on a destitute and delusional companion. The film is not merely self-referential, but also self-critical on Gilliam’s part. With Toby a stand-in for the director, Gilliam is not beyond acknowledging his own downfalls by way of the character. Toby can be cruel, narrow-minded, chauvinistic, and impulsive—he leaves the set of his commercial behaving “like a fucking child,” says one of his crew, recalling the way many on Gilliam’s 2000 production questioned his professionalism.

The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is about Gilliam, to be sure, but it’s deeply felt. “We become what we hold onto,” says one character, and Gilliam has held onto this film for a long, long time. It’s apparent that both the director and his film are interchangeable now. And so, when Pryce’s Quixote meets the same fate as the hero of Cervantes’ book and dies after recovering his sanity, he realizes his dreams of knighthood were a delusion. In a way, like Gilliam, he was better off dreaming. There’s nothing more confronting in Gilliam’s work than the death of a dreamer, as evidenced in Brazil. But when Quixote dies, it’s because of Toby, and the incident reveals that the characters were two halves of Gilliam. Quixote was the dreamer and pure artist that inhabits Gilliam, whereas Toby is the filmmaker who, while a creative, nonetheless must deal with the business side of things—producers, financiers, and insurance companies. But in the end, Toby can no longer tell the difference between his life and the story he wants to tell. He rides off into the distance, occupying both roles at once. Undoubtedly, this is how Gilliam feels about his career and The Man Who Killed Don Quixote, a film about the ugliness of reality as this director sees it, and his long history with developmental hell and troubled productions—all of which stand in the way of his own dreams.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review