The Magnificent Seven

By Brian Eggert |

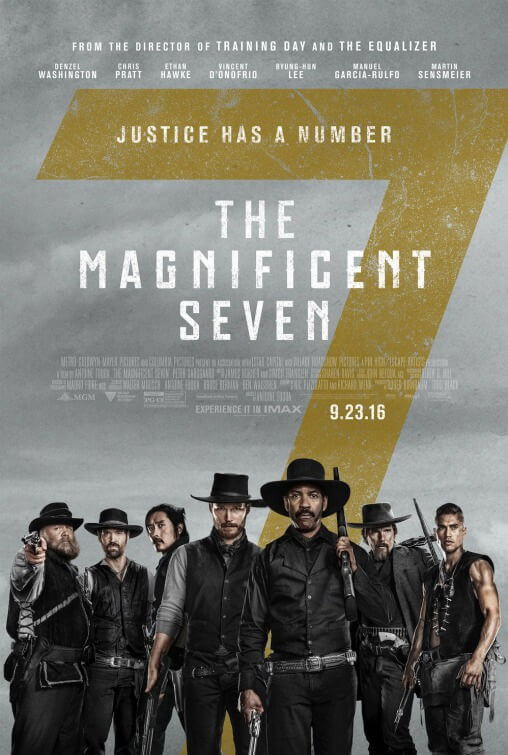

Director Antoine Fuqua’s The Magnificent Seven ends with a scene that almost single-handedly ruins the few worthwhile qualities about the two-hours-and-fifteen-minutes that came before. After exhausting Western shootouts and a rousing climactic sequence, Fuqua’s film tacks on a postscript, clearly added long after principal photography had wrapped and the tactile sets had been demolished. A computer-generated image of the dusty Western town appears before us, its artificiality a stark contrast to the practical setpieces and wilderness locations that occupy the rest of the picture. Then, the film’s only narration, spoken by Haley Bennett, praises the titular gunfighters as heroes: “They were… magnificent,” she says, in a moment that achieves a level of corniness that almost seems satirical, except it’s not. Then again, an embarrassingly bad ending isn’t all that’s wrong with The Magnificent Seven. There are also issues of questionable morality and half-hearted racial diversity to consider.

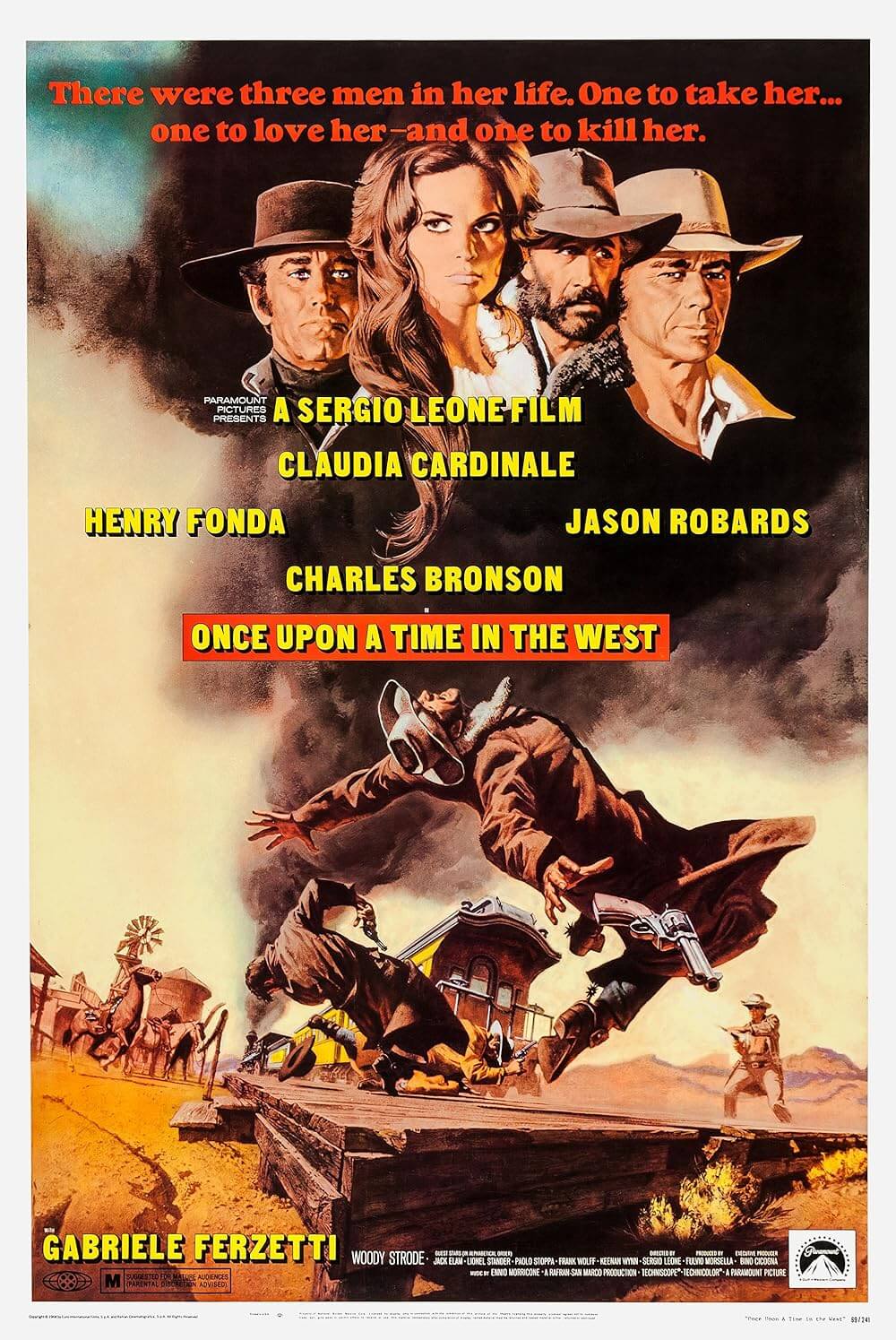

Fuqua’s film was based on John Sturges’ serviceable 1960 release, which was not so much an original as a reformatting of Seven Samurai, Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 masterpiece-to-end-all-masterpieces. Still, Sturges’ picture had enough Hollywood production value and a stellar ensemble (Yul Brynner, Eli Wallach, Steve McQueen, Charles Bronson, Robert Vaughn, James Coburn, etc.) to entertain. It also resulted in three beleaguered sequels and a television series, all of which had nothing in common with Sturges’ film save for Elmer Bernstein’s iconic theme. However, none of the remakes, or remakes of remakes, achieved the same level of epic scope, social commentary, or narrative complexity as Kurosawa’s original.

The latest version of The Magnificent Seven takes place in the 1870s and follows the basic story to the letter, where a small village hires a band of outlaws to protect their land from villainous intruders. The scenario has been moved from a Mexican village to a growing town on the American frontier called Rose Creek. The citizens of Rose Creek have been threatened to abandon their homes by Bartholomew Bogue (Peter Sarsgaard), a heinous criminal with a history of wiping out homesteaders and small villages by force to take their land as his own. When her husband dies after Bogue’s latest threat to the townspeople, Emma Cullen (Haley Bennet) seeks out hired guns to protect her town from Bogue’s small army of bad guys. She quickly aligns with an experienced gunslinger-turned-warrant-officer named Chisolm (Denzel Washington), who helps Emma hire six other experienced fighters to protect Rose Creek from Bogue’s impending invasion.

Fuqua’s film boasts a cast of talented, scenery-chewing actors. Chris Pratt appears as John Faraday, a hard-drinking con artist who behaves like a man out of time. No matter how genial his presence onscreen, Pratt maintains a very contemporary persona and performs dialogue that consists of modern colloquialisms, as though someone put Star Lord in a Western. Ethan Hawke gives the film’s most interesting performance as famed sharpshooter Goodnight Robicheaux, who, stricken with cowardice, has partnered with knife expert Billy Rocks (Byung-hun Lee). Manuel Garcia-Rulfo plays Vasquez, who fulfills the role of a Mexican outlaw and doesn’t seem to have an identity beyond his ethnicity. The same goes for Red Harvest (Martin Sensmeier), the Comanche warrior of the group. Vincent D’Onofrio’s mountain man Jack Horne also joins, bringing a curious idiosyncrasy to his performance that recalls the Bear Man from True Grit (2010).

Those familiar with the story will discover few surprises in Fuqua’s take, as the seven arrive in Rose Creek to some initially reluctant townsfolk. Before long, Chisolm wins their trust, and together they fortify the town for battle. After much build-up and some training sequences, Fuqua captures the final shootout with diverting excitement, the death toll and violence bringing into question the film’s PG-13 rating. Mauro Fiore’s lensing renders the action with clarity, although editor John Refoua’s cutting establishes a confused understanding of geography as the battle unfolds. Production designer Derek R. Hill constructs a believable Western village that looks like more than just façades on a studio lot, just as costumer Sharen Davis adorns the actors with believable dress. Nevertheless, our suspension of disbelief is challenged once CGI explosions and animated smoke appear onscreen.

Beneath the basic setup, screenwriters Richard Wenk (Fuqua’s The Equalizer) and Nic Pizzolatto (HBO’s first season of True Detective) instill a problematical moral theme to the Western violence. Bogue, an over-the-top capitalist villain, begins the conversation about righteousness when he preaches, “This country has long equated democracy with capitalism, and capitalism with God.” And so, Bogue makes a silly claim to godliness. At this, Emma tells Chisolm she wants “Righteousness… but I’ll take revenge.” As it turns out, Emma can achieve both. Her righteous revenge becomes morally correct by the film’s final scenes, when Emma and Chisolm carry out a form of Old Testament justice on Bogue from inside Rose Creek’s church. This suggests Chisolm is a holy warrior of some kind, presenting an archaic, but no less cathartic, strain of justice that should feel outdated and morally simplistic for today’s audiences.

This brings me to another major problem with The Magnificent Seven—present in both Sturges and Fuqua’s versions. In Seven Samurai, Kurosawa complicated the situation by depicting the villagers as capable of misdeeds and ugly, selfish acts; he also included scenes that justify the villagers’ suspicions about samurai, who often prey on farmers. The interactions between samurai and villagers were meaningful and multi-layered, making the conflict of Seven Samurai more intricate than simply Good vs. Evil or Moral vs. Wicked. However, Sturges’ film depicted the Mexican villagers as pure, defenseless souls, perhaps as a reflection of America’s perceived need to defend the innocent in Vietnam at the time. Fuqua shows Rose Creek’s inhabitants to be anonymous, albeit decent people, while despite being outlaws and killers, the heroes have nothing but good intentions. As a result, there’s no question about whether or not the people of Rose Creek deserve protection, nor about the heroes’ intentions toward the villagers. And given this narrative straightforwardness, both versions of The Magnificent Seven prove far too simplistic.

Earlier in this review, I made reference to some of the film’s ethnic choices being problematic. Despite a refreshing diversity among the cast, which includes the surviving members of the seven being entirely non-white characters, a few details remain suspect. Consider Red Harvest, whose name channels Kurosawa on several meta levels. Red Harvest is the resident Native American and sidekick to the heroic leader, but the filmmakers decided the villain also required a Native American sidekick. Alongside Bogue stands a bow-and-arrow wielding Native credited as Denali (Jonathan Joss). Of course, these two Native American characters, the only two in the film, must come face-to-face, fighting with knives and tomahawks in an eye-rollingly convenient battle of racial exclusivity.

Undertones such as this prove disturbing, not to mention historically inaccurate. Consider how Rose Creek seems to have no prejudices about Chisolm, a man of color, barking orders alongside a Mexican, an “Indian”, and an “Oriental”. A single scene where some racist, rednecked naysayer speaks against the town’s new multiracial leaders, only to be put in his place, would have made race an essential and important issue in the film. Nevertheless, Rose Creek manages to be the most progressive and unprejudiced town in the history of the Old West. Perhaps most troublesome of all is the filmmakers’ choice to change the small town from a Mexican village to an American one. This decision reflects a sad reality: that our present country is divided about whether we should build a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border. In response, the writers arguably changed the original story so as not to displease a large segment of their audience with prejudices against Mexico, and in doing so, the filmmakers demonstrate and support a disturbing undercurrent prevalent in American society today.

Instead of preaching the film’s potential themes of tolerance and injustice, Fuqua’s The Magnificent Seven remains subtextually contradictory. This is a narrow-minded, subtly mean-spirited remake. Fans of the cast may enjoy a few moments in the performances of Pratt, Hawke, Lee, and especially the charismatic Washington, who does wonders with his underdeveloped role. But the film mostly squanders its talented cast on a silly dynamic that tries to associate revenge with righteousness. On the whole, the film’s predicable plot turns and unsophisticated style represent a dull, crowd-pleasing effort that fails to justify itself as a remake. In fact, many of Fuqua’s thematic choices echo unsettling trends in tokenism, race, and morality that not only do Kurosawa’s honorable original a disservice by association, but they present a wasted opportunity to improve upon Sturges’ one-dimensional version.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review