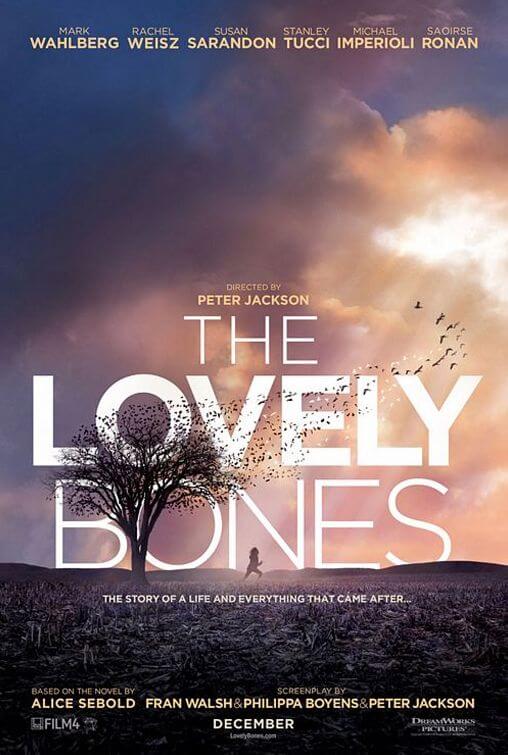

The Lovely Bones

By Brian Eggert |

Some stories on the printed page are best left to the imagination where your mind fills in the blanks. A film does the job of replacing those blanks with actors, camerawork, editing, and special effects. This process takes something away from the experience of reading, wherein the possibilities are endless in the mind’s eye. The majority of films based on books lose something in translation because in a film we only know what we’re told—this problem has existed since the beginning of the film industry when audiences were first disappointed with poor book-to-film adaptations. Occasionally, movies can complement their literary sources (The Lord of the Rings), and in very, very rare cases, even surpass them (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest). Some books are even considered “unfilmable” (Naked Lunch). However, those sometimes make the best movies.

In consideration of director Peter Jackson’s adaptation of The Lovely Bones, based on Alice Sebold’s best-selling novel, it’s clear that her book wasn’t meant for film, or at least it wasn’t meant to be made by this filmmaker. But if Jackson can’t do it, who can? Aspects of the story that work on the page become heavy-handed on the screen. Whether the film exposes the faults of the book, or the book is just unfilmable, or a combination of the two, one cannot be sure. What’s definite is that Jackson has made the worst film of his thus-far stellar career, having lost the story in a meandering structure and an over-emphasized whirl of computer effects. Not one aspect of the story works the way it’s supposed to, and the result can only be described as an epic disaster from a director whose films are usually epic successes of artistic and commercial bravado.

The first thing we’re told by our narrator Susie Salmon (Saoirse Ronan) is that she’s dead, murdered on December 6, 1973, at the age of 14. She goes on to describe her happy life with her kindly and loving parents, Abigail (Rachel Weisz) and Jack (Mark Wahlberg), her younger sister and brother, and her candid, hard-drinking grandmother (Susan Sarandon). She has a crush on a boy in her class, Ray (Reece Ritchie), who proves to be the ultimate missed opportunity when one day after school on the walk home she’s murdered. Susie explains that she lived in a time before the faces of missing children were on milk cartons, so child murderers weren’t profiled as unshakably as they are today. The killer, we learn, was her reclusive neighbor, George Harvey (Stanley Tucci, who’s wonderful in his role, despite phony-looking color contacts). No one but Susie’s sporty sister Lindsey (Rose McIver) suspects him. Harvey lures Susie into an underground room that he constructed in a cornfield, and from thereon out we only see her in the afterlife.

From a place between life and Heaven, Susie prepares herself to let go of her loved ones and move on. While she watches over her family, our narrator meets Holly (Nikki SooHoo), who’s just sort of there with Susie but never really does anything. Susie spends most of her time looking down on the potential capture of Harvey, as the psychopathic predator begins concocting plans to murder Lindsey after the police investigation calms. The scenery of Susie’s own private afterlife is emotionally vapid, and Jackson seems intent on spending too much time there, which cuts short the audience’s time with the family—the very centerpiece of the story’s emotional pull.

From a place between life and Heaven, Susie prepares herself to let go of her loved ones and move on. While she watches over her family, our narrator meets Holly (Nikki SooHoo), who’s just sort of there with Susie but never really does anything. Susie spends most of her time looking down on the potential capture of Harvey, as the psychopathic predator begins concocting plans to murder Lindsey after the police investigation calms. The scenery of Susie’s own private afterlife is emotionally vapid, and Jackson seems intent on spending too much time there, which cuts short the audience’s time with the family—the very centerpiece of the story’s emotional pull.

Jackson has enlisted his visual wizards at WETA Workshop to design an entire world for Susie’s ambiguous In-Between. All manner of grandiose backdrops, animated with computers, look surprisingly shoddy. What’s more, the images are the worst kind of generic symbolism—everything from birds to flowers to water. Every moment of Susie in her limbo looks like Ronan is standing in front of a green screen. Massive ships-in-a-bottle crash together on a beach; an orb-like world meant to reflect Susie’s penguin snowglobe, floats in a vast blue sky, sporting bright trees and impossibly green grass; she stands on a gazebo and looks into the distance toward her family. These should be awe-inspiring images, except they’re entirely empty. And Jackson can find no better way to mesh this all together than through an endless barrage of fades to white.

This is a marathon of failed emotional connections. What could be more passive than a dead teenager looking down on the people in her former life, not necessarily interacting but echoing her presence in a faded, reflexive way? Caring about Susie, beyond the basic empathy we feel for a murdered 14-year-old, is almost impossible in her state in the film. She does little more than look down on her family and regard her limbo with wonder. Her presence in the In-Between has no real meaning conveyed—what is her purpose there? Susie doesn’t know or question what she must do before she can move on, and when she eventually figures it out, it’s so late in the game that the viewer has lost interest. She’s not lingering for any purpose communicated in her narration or actions. She just remains behind, if only to give the audience an excuse to watch her family with her.

Meanwhile, the living characters spend their time brooding over the loss of Susie. Her mother refuses to address the problem until the final moments; she’s the kind of mother who abandons her two youngest children because she can’t cope with losing her eldest. Too bad, because Weisz was the best thing onscreen until her character disappears altogether. At least Susie’s father Jack is proactive, obsessive even, about catching the killer. Although, Wahlberg is clearly in over his head with the role. But therein resides a problem. Jackson isn’t quite sure if he wants to make a drama about people coming to terms with the death of a loved one, or if he wants to make a suspenseful thriller about catching a murderer. He doesn’t decide, so instead, he smashes the two together, and neither receives full attention. The detective story, with Jack hunting for clues to his daughter’s murderer in the neighborhood, lasts until Jack gets hurt, and then Wahlberg almost disappears from the film.

The biggest problem is that Jackson pulls punches when it comes to content (you may want to skip over this paragraph if you’d prefer to avoid major spoilers). In the film, Susie’s grandmother tells her that she gave her first kiss to an older man. That idea plants a seed of dread in the viewer because at this point we know an older man will eventually kill Susie. In the book, however, Susie isn’t just simply murdered by Harvey, she’s raped. This isn’t even implied in the film. She’s deflowered by a monster in the book, and part of her goal in the In-Between is to somehow salvage what Harvey took from her. To accomplish this, she possesses Ray’s new girlfriend, Ruth, and loses her virginity all over again, reclaiming a crucial piece of her life that was taken. None of this is mentioned in the film (Susie instead embodies Ruth to get her first kiss with Ray), likely to maintain a PG-13 rating, though even implied sexuality would’ve made the flower imagery throughout all the more significant.

The biggest problem is that Jackson pulls punches when it comes to content (you may want to skip over this paragraph if you’d prefer to avoid major spoilers). In the film, Susie’s grandmother tells her that she gave her first kiss to an older man. That idea plants a seed of dread in the viewer because at this point we know an older man will eventually kill Susie. In the book, however, Susie isn’t just simply murdered by Harvey, she’s raped. This isn’t even implied in the film. She’s deflowered by a monster in the book, and part of her goal in the In-Between is to somehow salvage what Harvey took from her. To accomplish this, she possesses Ray’s new girlfriend, Ruth, and loses her virginity all over again, reclaiming a crucial piece of her life that was taken. None of this is mentioned in the film (Susie instead embodies Ruth to get her first kiss with Ray), likely to maintain a PG-13 rating, though even implied sexuality would’ve made the flower imagery throughout all the more significant.

Overly simplified and curiously uninvolving, The Lovely Bones is a major disappointment, and an example of how this sort of ruminative, spiritual storytelling isn’t meant for film—at least not in the way that Jackson has presented it. Movies about the afterlife (think What Dreams May Come) almost never work because visualizations of a place that has only existed in the human imagination never materialize in a satisfying way. But more than that, Jackson has failed to make Sebold’s novel into the emotionally echoing piece it could have been by drowning out the feelings with a garish and unfocused presentation. At once, the director is doing too much visually while not doing enough dramatically. If only Jackson could have escaped the idea of the afterlife, perhaps he could have let his character do so as well.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review