Reader's Choice

The Lost Daughter

By Brian Eggert |

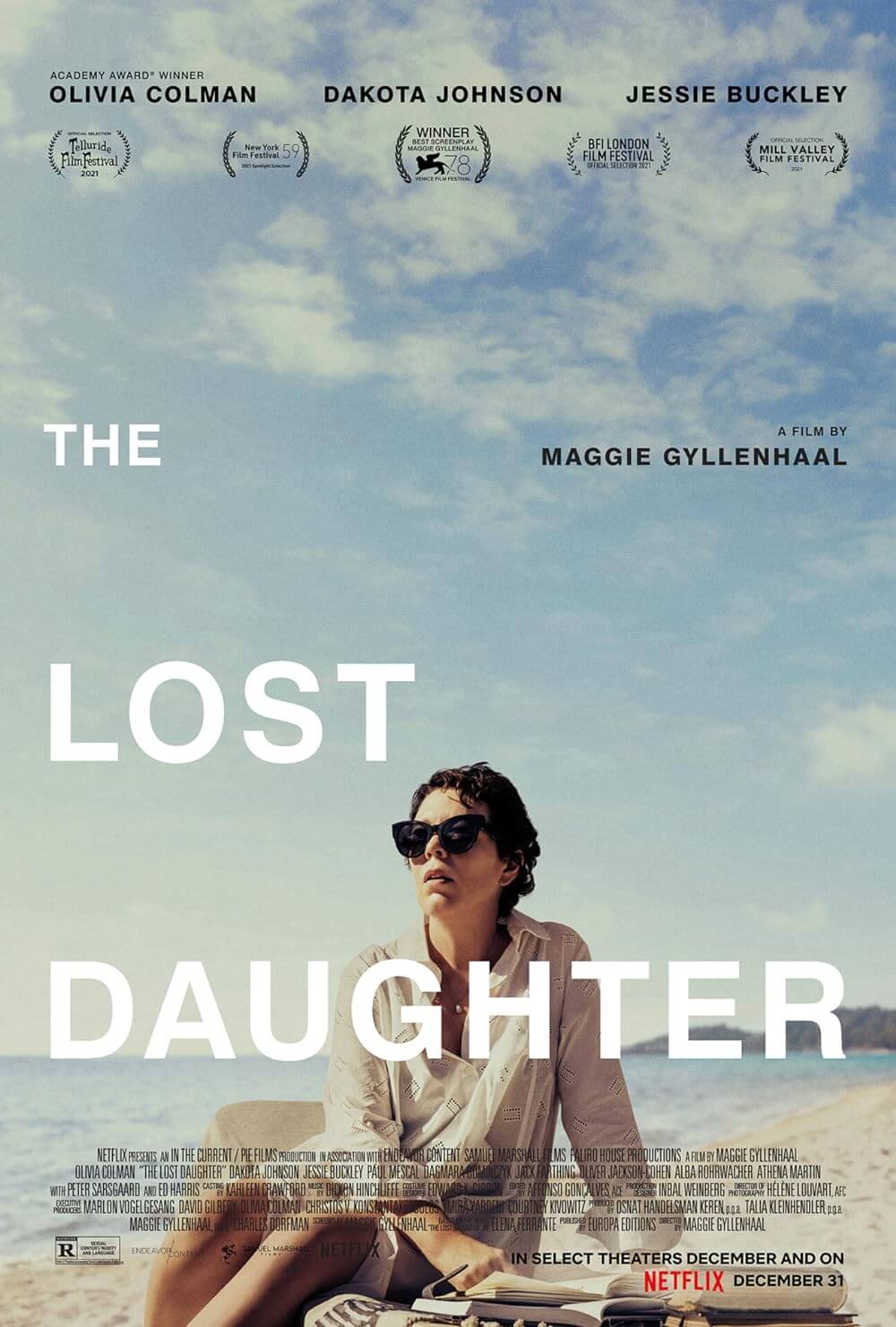

Ask what motherhood means to them, and most mothers will tell you that it’s a gift and their children are miracles. Despite the stress and lack of sleep, “It’s all worth it.” However, Leda Caruso, the character played by Olivia Colman in The Lost Daughter, might have a different perspective. “Children are a crushing responsibility,” Leda says at one point, with emphasis on the adjective. The notion that a woman might find parenthood a less-than-fulfilling endeavor is an unpopular perspective for a species that reproduces without restraint. Adapted from Elena Ferrante’s 2006 novel of the same name, the film proves as fiercely independent as Leda, a character who feels held back by motherhood and defies every socially constructed expectation for maternal instincts. Ferrante admitted she “ventured into dangerous waters without a life preserver” with the book’s subject. The adaptation explores the pressure of motherhood on Leda—the assumption that she will nurture her children, the sense of failure when she doesn’t, the guilt she feels for pursuing her professional ambitions, and the enduring pain that causes her to lash out and ache inward many years later.

The film marks the directorial debut of Maggie Gyllenhaal, who also wrote the screenplay. It feels like the perfect material for Gyllenhaal, who, ever drawn to controversial and challenging roles, demonstrates the same ambition behind the camera. She and Ferrante make an ideal pairing of feminist voices, even if Ferrante is a curious case—starting with her pseudonym. Writing anonymously (surprisingly, in this day and age), she prefers to remain unknown to focus the discussion on her output. After all, it’s not difficult to imagine some media pundit drilling the author about her personal views, thus distracting from how readers engage with her ideas or interpret her narratives for themselves. “Books, once they are written, have no need of their authors,” Ferrante once wrote. Moved by the author’s work, Gyllenhaal wrote Ferrante a longhand letter (reportedly the only form of communication she accepts). Through their correspondence, she nabbed the rights to The Lost Daughter.

The resulting film is the kind Netflix produces exclusively for awards season, but don’t hold that against it. Leda, a professor, arrives in Greece for a vacation, carting suitcases full of books to continue her scholarly research. But something twists inside of her, and it has nothing to do with the bowl of moldy fruit in her room, the distracting lighthouse and foghorn out her window at night, or the casual passes made by the caretaker, Lyle (Ed Harris). Instead, when Leda’s quiet beach turns into a playground for a loud family and their unruly children, who invade her serene space like cockroaches, she bristles. They’re celebrating the birthday of Callie (Dagmara Dominczyk), a pregnant woman who asks Leda to move down the beach so they can use her spot. Leda refuses, showing the first glimpse of her meanness. It won’t be the last. Among the group is Nina (Dakota Johnson), a young mother whose grating child goes missing. Something about Nina interests Leda, prompting her to help search and even find the child playing nearby.

The Lost Daughter builds almost like a thriller. Despite the title, they find Nina’s daughter right away; however, the girl’s doll goes missing, prompting the child’s days-long meltdown that affects the entire family. It turns out Leda has taken the doll for reasons that become clearer as the story unfolds—and it’s a dangerous choice. “They’re bad people,” she is warned. How bad? One look from Nina’s husband (Oliver Jackson-Cohen) is enough to make us worry for Leda. And what will they do if they discover that Leda has stolen from a child? And why has she? This tension underscores the film’s flashbacks, revealing that the younger Leda (played by Jessie Buckley) nearly lost a child on a beach once and had a similar doll. Although Leda’s children are now in their twenties, the present-day incident with Nina reminds her of how she came to be vacationing on a beach alone in Greece. She thinks about her volatile and bitter relationship with her young daughters, her ineffectual husband (Jack Farthing), and how she eventually left them after launching into an affair with her intellectual counterpart (Peter Sarsgaard) at a conference. As she works through her memories, subtle suspense about the doll’s fate worms its way into the proceedings.

The Lost Daughter builds almost like a thriller. Despite the title, they find Nina’s daughter right away; however, the girl’s doll goes missing, prompting the child’s days-long meltdown that affects the entire family. It turns out Leda has taken the doll for reasons that become clearer as the story unfolds—and it’s a dangerous choice. “They’re bad people,” she is warned. How bad? One look from Nina’s husband (Oliver Jackson-Cohen) is enough to make us worry for Leda. And what will they do if they discover that Leda has stolen from a child? And why has she? This tension underscores the film’s flashbacks, revealing that the younger Leda (played by Jessie Buckley) nearly lost a child on a beach once and had a similar doll. Although Leda’s children are now in their twenties, the present-day incident with Nina reminds her of how she came to be vacationing on a beach alone in Greece. She thinks about her volatile and bitter relationship with her young daughters, her ineffectual husband (Jack Farthing), and how she eventually left them after launching into an affair with her intellectual counterpart (Peter Sarsgaard) at a conference. As she works through her memories, subtle suspense about the doll’s fate worms its way into the proceedings.

Gyllenhaal and editor Affonso Gonçalves create an impressionistic array of images that float between past and present. But the shots also linger. Cinematographer Hélène Louvart uses close-ups of Nina and the matriarchal Callie, who try to make sense of Leda and disentangle how her rudeness contrasts with her occasionally kind gestures. Though Leda views parenthood as an affliction, she half-heartedly talks about her daughters with parental pride, and others can see right through her feigned enthusiasm. Still, Leda is drawn to Nina, who faces a familiar turning point—the point where she can either become a nurturing mother or choose herself, as Leda once did, which some part of her regrets. Gyllenhaal shows us Leda’s choice in painful scenes, such as an excruciating moment when the younger Leda refuses to kiss the superficial wound on her daughter’s finger, leaving the girl to wail, finger outstretched and uncomforted. We see her envy two drifters (Alba Rohrwacher, Nikos Poursanidis) who have run away from their families for a nomadic lifestyle. And we see her resenting the love that holds her back.

There may be a few missteps in The Lost Daughter, such as the ending, which is one of those “Did she die or didn’t she?” conclusions that will spur debate—and may serve as a Rorschach test for viewers’ opinions about motherhood. That ending threatened to cheapen the film for me, along with some pronounced symbolism involving fruit and falling pine cones that, if you connect those ideas to motherhood, begin to feel somewhat overwrought (Lars Von Trier used falling acorns in 2009’s Antichrist to similar effect). But Gyllenhaal never loses focus on Colman, who gives arguably her best performance to date with harsh outbursts, blithe dancing to “Livin’ on a Prayer,” and a scene where Leda (cathartically) chides loud moviegoers. In the end, I wondered to myself whether Leda would make different choices if she could go back and relive them. I don’t think she would—and even if she did, she’d end up regretting that she didn’t pursue her career ambitions. “I’m an unnatural mother,” Leda admits at one point. Caught between the societal expectation that women become mothers and the personal desire to focus on her career, Leda feels an unresolvable inner conflict that something will be lost regardless of her choice. It’s a devastating realization, and The Lost Daughter is a rare representation of that honest perspective.

(Note: This review was originally suggested and posted to Patreon on January 6, 2022.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review