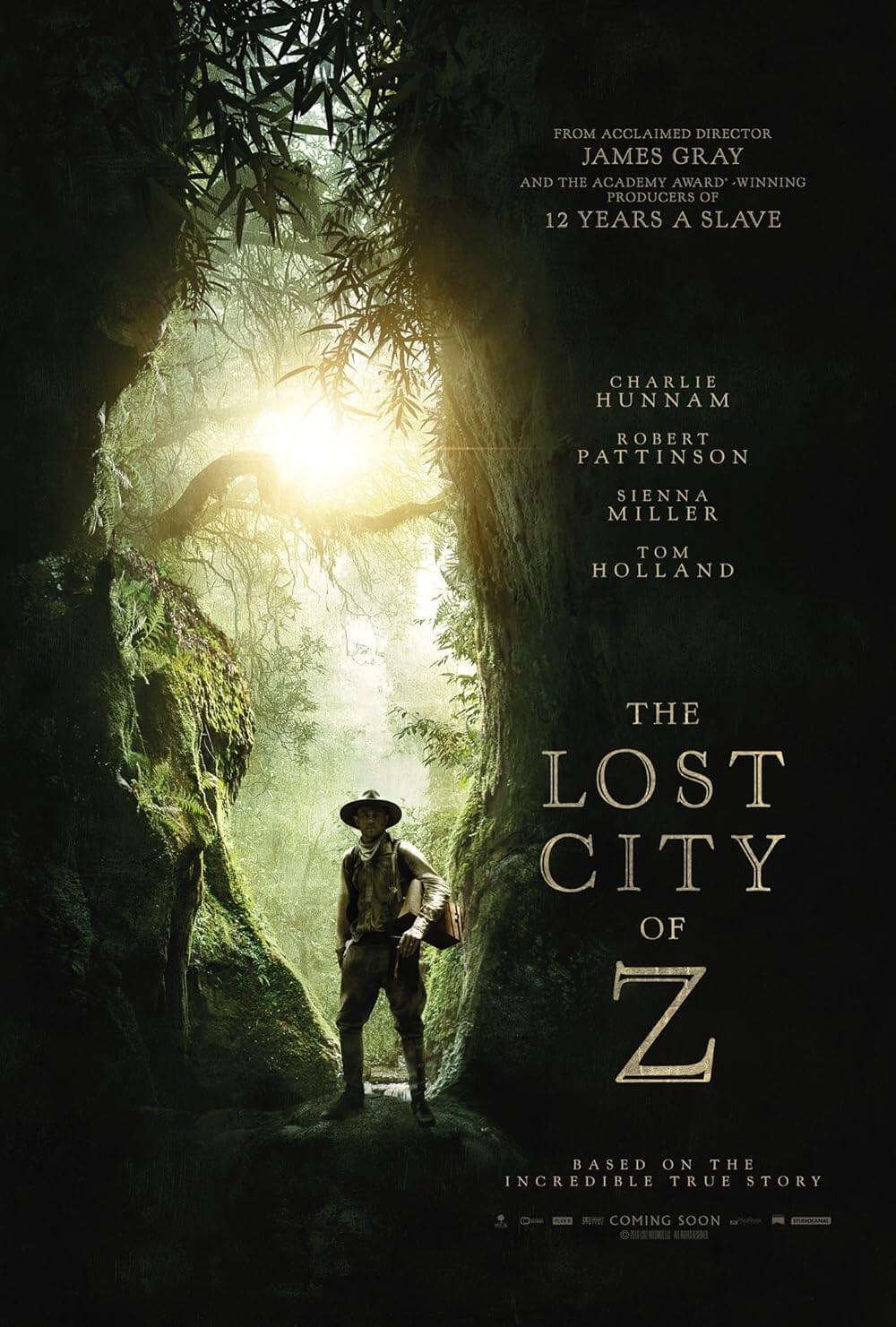

The Lost City of Z

By Brian Eggert |

The Lost City of Z, writer-director James Gray’s adaptation of David Grann’s best-selling work of historical fiction, unfolds in the style of David Lean’s great epics of yesteryear. British explorer Percival “Percy” Fawcett undertakes several journeys to Amazonia on behalf of the Royal Geographical Society in the early twentieth century, searching for an elusive ancient civilization he calls “Z” (or “Zed” in the British parlance). While the perilous journey and scenery might be enough, Fawcett represents the kind of inscrutable hero found in Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) or Lawrence of Arabia (1962)—characters longing for something unknowable perhaps even to themselves. Fawcett disappeared in 1925 somewhere in the jungles of Brazil, and Gray uses the real-life figure to form a kind of spiritual and ambiguous understanding about what compels the character, albeit through multiple contexts: historical, dynastical, romantic, feminist, postcolonial, humanist, and even mystic.

Gray’s film remains exceptional in part for everything it avoids being; namely, a conventional Hollywood production filled with computer-generated images lensed by digital photography. The Lost City of Z was shot on 35mm in Colombia using mostly natural light, and cinematographer Darius Khondji’s incredible footage was flown out of the jungle to be processed, a task that required a large percentage of the production’s rather small budget to complete. The visible textures and grain, along with a painterly surface to the footage, recall the low-light work of John Alcot on Barry Lyndon (1975). Rather than a glossy production designed to look like a movie, The Lost City of Z captures the look of a timeless piece of cinema. And to complete the naturalistic formal presentation comparable to Lean, Gray’s editors John Axelrad and Lee Haugen evoke perhaps the greatest cut in film history from Lawrence of Arabia to create a stunning visual bridge early in the film.

Hindered from advancement in British military society by his father’s reputation as a drunken gambler, soldier and explorer Percy Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam, never better) accepts a cartography mission in 1906, hoping to restore his family name. Alongside his faithful sidekick Henry Costin (Robert Pattinson, bearded, rather excellent), Fawcett sets out on the Amazon on an unimpressive raft. Disease, native arrows, and starvation are persistent threats. River scenes shot on Columbia’s Rio Don Diego recall those punishingly desperate, contemplative sequences on the actual Amazon filmed by Werner Herzog. Indeed, at several points in Fawcett’s initial journey—the first of three—Gray nods to Herzog, whether it be showing the explorers skeleton-thin and floating aimlessly downriver as the Conquistadors in Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), or the association to Fitzcarraldo (1982) when Fawcett discovers a jungle opera house run by a rubber baron (Franco Nero).

Eventually, Fawcett completes his mapping mission, and while doing so, he finds ancient pottery that suggests a civilization—not the gold metropolis of El Dorado per se, but an unknowable “Z” that remains to be discovered. After returning home, Fawcett restores honor to his family name but finds himself eager to return and search for his proposed city, much to the dismay of his wife Nina (Sienna Miller, also never better), and much to the incredulity of skeptical RGS members. The British colonialists maintain what Fawcett views as an outdated perspective on the Amazonian “savages.” He hopes to prove that ancient peoples are equal among human beings. He returns to Brazil for a disastrous expedition in 1911, and then again in 1925 for a fateful voyage with his son Jack (Tom Holland).

The Lost City of Z is extraordinary for sequences that another, lesser production would undoubtedly have cut to create a shorter runtime. Clocking in at nearly two-and-a-half-hours, the film carries on in a sprawling and novelistic fashion, complete with elaborate interludes that develop Fawcett and his wife into complex, humanist characters. Though Gray alters the real story for the sake of his audience, reducing the number of Fawcett’s actual trips to the Amazon by more than half, the filmmaker also recognizes that the journey belongs not merely in South America but also throughout Europe. An extended World War I segment mid-film features trench warfare that shows Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (1957) as an apparent influence and, afterward, a fortune teller’s visit to a bunker solidifies Fawcett’s destiny in a transcendent reading. Meanwhile, Hunnam embodies Fawcett as a determined man divided by love for his family and a destiny that awaits him in the unknown, seeing the persistent “Z” in his mind’s eye.

The Lost City of Z is extraordinary for sequences that another, lesser production would undoubtedly have cut to create a shorter runtime. Clocking in at nearly two-and-a-half-hours, the film carries on in a sprawling and novelistic fashion, complete with elaborate interludes that develop Fawcett and his wife into complex, humanist characters. Though Gray alters the real story for the sake of his audience, reducing the number of Fawcett’s actual trips to the Amazon by more than half, the filmmaker also recognizes that the journey belongs not merely in South America but also throughout Europe. An extended World War I segment mid-film features trench warfare that shows Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (1957) as an apparent influence and, afterward, a fortune teller’s visit to a bunker solidifies Fawcett’s destiny in a transcendent reading. Meanwhile, Hunnam embodies Fawcett as a determined man divided by love for his family and a destiny that awaits him in the unknown, seeing the persistent “Z” in his mind’s eye.

Moreover, the treatment of Fawcett’s wife could have been another in a long line of dutiful adventurer wives who remains home and raises the children. Granted, that is precisely what Nina must do, but the film resolves to develop her character into an outspoken First Wave feminist willing to challenge her husband’s views. Fawcett takes a postcolonial view of the Amazonian natives, questioning the widespread disbelief that such tribes could build a civilization; in fact, he argues that his proposed “Z” predates any white man’s civilization. And yet, when he refuses to allow his wife to join him on his 1911 exhibition, Nina confronts his sexism and hypocrisy in a scene that places Fawcett’s aspirations in context and qualifies them. Hunnam and Miller occupy the roles of people who are too intricate—and flawed—to be wholly defined by a single purpose or ideology, rendering their characters continually fascinating.

Gray’s willingness to question his hero’s actions and choices once again places The Lost City of Z in the same stratosphere of a Lean epic. T.E. Lawrence and Colonel Nicholson may have been the heroes of their respective Lean films, but they remain deeply imperfect and enigmatic characters driven by passions unknowable even to them. Fawcett feels similarly multifaceted in how the final implication—that Fawcett and Jack somehow lived out their last years among native tribes—brings much into question: Why did he never send for Nina and their other children? If he did find “Z”, why did he never seek to publish his findings? The mystery surrounding certain aspects of Fawcett’s disappearance and his views on the sublime integrity of Nature deepen the film with gravitas and refuse to suggest answers that do not exist, quite satisfyingly so.

Although Fawcett’s family name had long since been established, something keeps drawing him back, and Gray explores the possible reasons for his searching in a wonderfully made film. From start to finish, the viewer may feel tested by the measured pace and unsensational approach to the storytelling that clashes with today’s loud standards, but the rapturous production and thoughtful examination of its characters cannot help but enthrall. For every scene that explores the mysteries of the Amazon, there is an intimate counterpart with Fawcett’s family, such as the mournful period after the war as he recovers from his wounds. The Lost City of Z contains a rare kind of grandeur and intimacy that only filmmakers like Lean or Anthony Minghella (The English Patient) have achieved before, a singular and uncommon form of epic filmmaking that others imitate but lack the artistry and patience to create. Gray has drawn on his influences without feeling derivative, and the result is a film whose mood and skill represent a rare, truly cinematic epic.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review