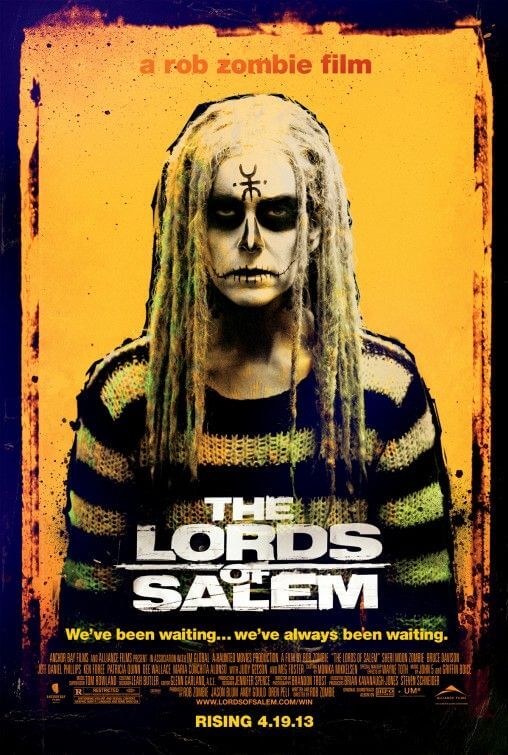

The Lords of Salem

By Brian Eggert |

Although Rob Zombie’s The Lords of Salem doesn’t focus on yet another group of southern-fried, gutter-mouthed psychopaths, as done in his previous Tobe Hooper wannabe flicks (House of 1,000 Corpses, The Devil’s Rejects, and his Halloween remakes), the metal-rocker-turned-filmmaker pays homage to his favorite horror movies from yesteryear in other ways. Whereas before, his influences ranged from Hooper’s original The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) to the works of John Carpenter, here Zombie resolves to take a creepier, more atmospheric, and slow-burning approach recalling the impending doom from Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980) and Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Rather than chaotic violence and abrasive characters soiling every frame, Zombie tries to develop a pervading sense of dread punctuated by unsettling imagery. Despite his efforts to try something different, the resultant film feels derivative, unscary, and eventually nonsensical.

Of course, had Zombie just made another terror show about a band of serial wackos, I would have probably felt frustrated and annoyed afterward, as this is often my reaction to his work. Instead, I felt unaffected and indifferent, which is another kind of bad reaction altogether. In the prologue, we hear a corny diary entry from seventeenth-century witch-hunter Reverend Jonathan Hawthorne (Andrew Pine), and the curse uttered by the nasty coven leader (Meg Foster) he sets ablaze. Cut to modern-day Salem, where Zombie’s protagonist is played by his wife Sheri Moon-Zombie, whose obnoxious, whiny-voiced, ever-nude presence in the director’s earlier films proved to be tiresome. Much like her husband, she’s toned down for The Lords of Salem as well (but no more clothed). Under blonde dreadlocks, she plays a recovering addict and radio DJ named Heidi. On her late-night show “Salem Rocks,” Heidi airs a mysterious vinyl from a band called “The Lords,” and the eerie sounds induce an almost catatonic response from the women of Salem, her worst of all.

After Heidi first hears the tortured sounds from the record, all manner of weird events take place around her. She drifts in and out of morbid dreams, many involving the vacant Apartment 5 down the hall and her building’s trio of clingy middle-aged women (Patricia Quinn, Dee Wallace, Judy Geeson) who seem curiously preoccupied with her. Foster’s head witch Margaret Morgan appears here and there to speak some ghastly incantation or threaten a hellish demise; sometimes, she appears as an apparition that no one but the audience sees, and other times she appears in Heidi’s nightmares. Heidi’s fellow disc jockeys (Ken Foree and Jeffrey Daniel Phillips), both named Herman, show concern over her odd behavior but don’t get too involved in what they assume is a relapse. Meanwhile, local witch authority Francis Matthias (Bruce Davison) pokes his nose where it doesn’t belong; we suspect he might be able to help Heidi, but predictably, his fate ends up something like that of Scatman Crothers in The Shining.

Indeed, there’s more than one reference to Kubrick’s celebrated horror masterpiece. Zombie broods on shots down long corridors, his camera dwells on the dreaded apartment number 5, and each day in Heidi’s progressing situation is announced by onscreen titles—all The Lords of Salem needed was a young boy riding a Big Wheel on the alternating carpet and woods floors to make Zombie’s homage complete. His own touches of dread consist of gross little creatures and haunted house visuals abound: overhead hallway lamps move on their own; transparent ghosties linger in the dark; strange sound effects pulsate and grind away; a dwarf in a gory monster outfit flails its arms and tendrils; a towering harry beast emerges from fire; death-faced religious figures play with dildos; naked witches dance in circles and chant unintelligible satanic mumbo-jumbo. What do all of these images and sounds mean? Who knows and, after more than an hour without any clear stakes, who cares?

Worse than Zombie’s uncanny and continued talent for putting unsympathetic characters into dire circumstances, he uses imagery in The Lords of Salem that’s disgusting and bizarre, but also inexplicable and possibly pointless. In the finale, audiences must endure a trance-like ceremony filled with jarring cuts, dry humping, goat-riding, and the animated melting faces of Christian icons. But to what end? Afterward, I was at a loss to find any meaning to what I had seen, be it dramatically, emotionally, or logically. Whereas The Shining and Rosemary’s Baby build gradually and with purpose, Zombie ignores the layers of his influences and goes straight for a primitive scary experience, but he never delivers a payoff. After putting his audience through his own sordid witch trials, he ends the film without even the vaguest sense of closure. Set aside Zombie’s inspired casting of genre favorites (like Wallace, Sid Haig, and Michael Berryman) and his film barely holds our interest. Neither suspenseful nor disturbing as intended, The Lords of Salem may resist Zombie’s previous shock-fest style, but his detour into goat-sacrificing Satanism doesn’t prove any more watchable.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review