The Lone Ranger

By Brian Eggert |

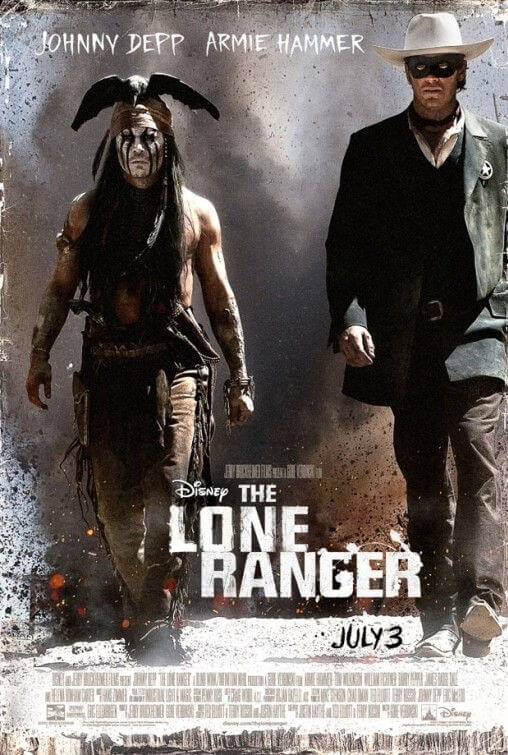

Gore Verbinski’s The Lone Ranger is the sort of film that today’s more reactionary critics and moviegoers will reexamine a few years from now and describe as “misunderstood.” An ambitious Western blockbuster produced by Jerry Bruckheimer and released by Walt Disney Pictures, this summer movie extravaganza has been modeled after Pirates of the Caribbean in nearly every respect, from the somewhat supernatural plotline to the outlandish action setpieces, straight down to star Johnny Depp embodying another hero defined by his physical comedy. And yet, underneath special FX-laden exploits and a seemingly never-ending procession of action sequences lies a picture with something to say about the American West and the sordid history of the United States. A novel concept for a major Hollywood adventure released to coincide with the Fourth of July holiday weekend. Granted, the cynical undertone is mostly overshadowed by the picture’s scatterbrained quality and tonal inconsistencies, but the end result may find enthusiasts among those willing to look a little deeper.

Verbinski helmed not only the first three Pirates of the Caribbean films but one of the best Westerns of the last decade, which also happened to be an animated picture about an existential chameleon. With Rango, Verbinski played in the Western sandbox, building a strangely philosophizing, gorgeously animated, and lovingly detailed genre piece that heralded both animation and Western styles. Nothing so monumental is achieved in The Lone Ranger; nevertheless, the film must be admired for its excess ambition and evident love of the genre. Just as he did on Rango, Verbinski makes visual and orchestral nods to Western directors ranging from John Ford (The Searchers) to Sergio Leone (Once Upon a Time in the West) to Sam Peckinpah (The Wild Bunch), while also repeating the breathless energy of his pirate franchise. Some will find The Lone Ranger’s reliance on a proven formula obvious and insulting—after all, it’s apparent how the studio assembled the same producer, director, writers, and star to repeat the success of their seafaring franchise. Still, Verbinski’s palpable enthusiasm outweighs the commercial quality of the film.

Popularized on the radio in 1933, “The Lone Ranger” brand, all the rage with children and adults alike, went on to early television fame in the 1950s with a hugely successful show starring Clayton Moore as the titular white-clad hero and Jay Silverheels as Tonto, the ranger’s trusty Native American sidekick. Set to the theme of Rossini’s “William Tell Overture” and boasting romantic-but-naïve views of the Wild West, the franchise name has been embedded into our cultural awareness ever since. Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, writers and co-producers of the Pirates of the Caribbean series, co-wrote The Lone Ranger script, and their efforts afford the material with the same breakneck pacing and nonstop energy of the Pirates franchise, perhaps to a fault. But they’ve co-written with Justin Haythe, who adapted Richard Yates’ devastating novel Revolutionary Road for the screen in 2008, and imbues The Lone Ranger with the same air of distrust for American romanticism as that film. The two styles—high-energy escapism and profoundly trenchant historical observance—never quite marry onscreen.

In a charming framing device crucial to the film’s integrity, we open in 1933, after “The Lone Ranger” radio program captured the hearts of American children. At a San Francisco fair, a boy (Mason Cook) donning Lone Ranger garb wanders into a Wild West show and witnesses what he believes is a motionless “Noble Savage” statue come to life. Aged and senile, a wrinkled Tonto (Depp) recounts his exploits in 1869 with hero John Reid (Armie Hammer). This is not so strange. After all, many Native Americans who fought white men in the 1800s made their living late in life by appearing in the famous Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show—among them even Sitting Bull—so it stands that the once heroic Tonto might end up here. At any rate, the elder Tonto is portrayed as somewhat unhinged in his old age (not to mention in his youth; more on that later), and as the story is told from his perspective, the more outlandish elements of the ensuing plot find some reasoning in their pointed lack of reasoning. As a result, the film frequently cuts back to 1933, as the boy questions the logic of Tonto’s story. But throughout, it’s vital to remember: this is a story told by an unreliable narrator.

In the 1869 setting, we’re dropped into Colby, Texas, where railroad tycoon Latham Cole (Tom Wilkinson) brings the steam engine to his little town to usher in progress. On a train bound for Colby is outlaw Butch Cavendish (William Fichtner), who escapes and eventually kills Texas Ranger Dan Reid (James Badge Dale), leaving Reid’s wife Rebecca (Ruth Wilson) and boy Danny (Bryant Prince) alone. Determined to protect them is Dan’s lawyer brother John (Hammer), who seeks revenge only after Tonto returns him from the dead. Now masked and believed to be invincible, the Lone Ranger mounts his snow-white horse Silver and, with Tonto beside him, hunts down Cavendish. Of course, Cavendish is just one part of a larger conspiracy involving faked Comanche raids, a silver mining conspiracy, the genocide of at least two Native American tribes, and the manipulation of the Cavalry (headed by Barry Pepper’s Captain Fuller) to serve moneyed interests. Indeed, the filmmakers at least know their history, even if it’s apparent they failed science (the actionized exploits defy physics at every turn). All the while, Cavendish is believed to be a “Wendigo”—an evil presence that sets Nature “off balance,” resulting in borderline surreality from feral rabbits and Silver’s odd-but-hilarious behavior.

Although cast into a sidekick role, Depp is top-billed and steals the show, playing a thinly veiled Capt. Jack Sparrow under chipping white and black face paint. He’s eccentric and silly, adopting a “crazy Indian” persona wherefrom he generates a few guilty laughs (Depp’s Native American heritage remains unconfirmed), but the routine grows wearisome, and the attempts at comic relief wear thin over the film’s long two-and-a-half hour runtime. Still, the film offers Tonto a tragic backstory that speaks to the massacre of Native American tribes in the name of westward expansion, leaving the character’s oddball behavior explained as “scarred for life”—never a diverting notion. Next to Hammer’s one-note hero, however, Depp’s Tonto seems multi-dimensional. Hammer, best known from The Social Network, plays The Straight Man with such a bland quality that it’s difficult to understand why the filmmakers believed they could get away with such an underdeveloped protagonist, but perhaps, as we will see, this was intentional. Helena Bonham Carter also appears as a local Madame with an ivory leg. Fichtner, Wilkinson, Wilson, and Pepper each add layers to their respective roles by the actors’ onscreen presence alone.

The Lone Ranger begins to collapse when the adventurous and escapist high-wire fun is paired alongside an entire Native American tribe getting mowed down by machine guns. Sadly, the body count is very high, certainly far too high to appear under the Disney label. And grislier aspects of the story creep in, to shocking effect, such as Cavendish cutting into a near-dead someone and taking a chomp out of their heart. The film pushes its PG-13 rating to its limits. But Verbinski has something to say about the West here, and the bloody history Americans conveniently forget. He addresses a past defined by corruption and The Golden Rule, although in this case, it’s The Silver Rule. Yet he confuses his historical message by juxtaposing drastically different moods from one scene to the next, resulting in a bewildered viewer. The action scenes border on absurdist, such as an opening train crash that ends fortuitously, or Tonto engaging in more than one reference to Buster Keaton’s The General. Gory history lessons and escapism rarely blend well. At least, that’s the argument made by the majority of the film’s critics.

Consider instead how the entire story is seen through Tonto’s eyes, from a Wild West exhibition stationed next to the Freak Show at the San Francisco carnival. Therefore, the fact that Tonto’s story is over-the-top and unbelievable is justified and clarifies why he’s the central character, and why everyone else feels underdeveloped. Remember, Tonto is aged and possibly crackers, and he’s spinning this yarn for a child in 1933, so his storytelling may be tangential and unfocused. There’s no need for Tonto to develop The Lone Ranger character for a boy who already idolizes him—Tonto needs only to give the boy what he wants, a solid adventure with an unshakable hero. But at any moment in telling the story, he might recall and incorporate some tragic event or detail from his past, only to remember who his audience is, at which point he exaggerates the story even further to distract us from the truth. Whether or not you can accept this justification for The Lone Ranger depends on how much thought you’re willing to put into a summer blockbuster of this kind. Verbinski has thought much about his picture, cramming in countless film references and complicated ideas into a film not easily explained or defended. Even if, at times, the end result isn’t coherent or well balanced, it’s laudable in its defiance of the ordinary.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review