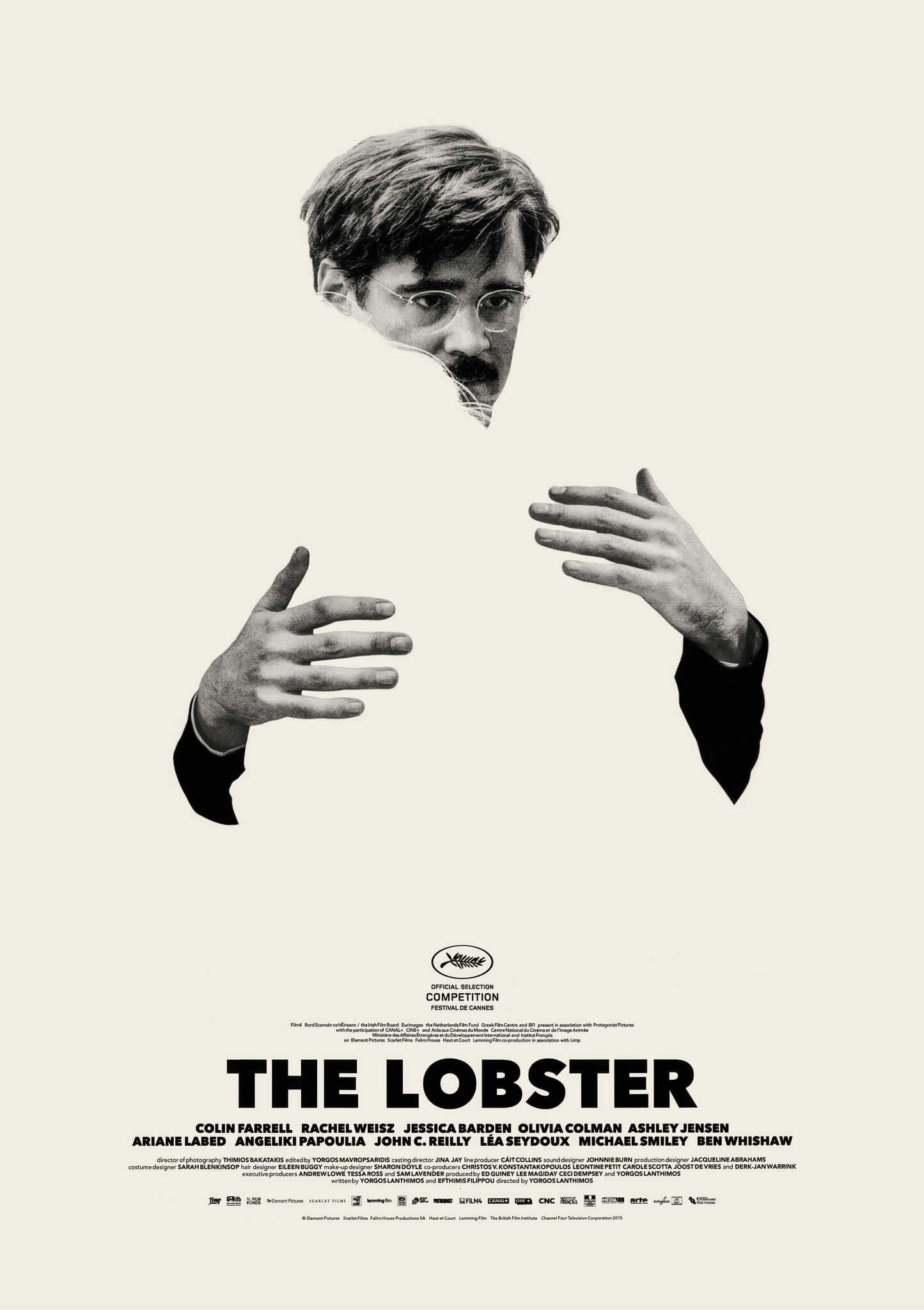

The Lobster

By Brian Eggert |

Is love when two people share similar identifying characteristics? Or is it their reproductive likelihood as a couple? Or perhaps it’s when your partner goes blind, and you resolve to stab your eyes out to join them in blindness? These and other metaphorical questions linger at the center of The Lobster, a thoughtful, funny, and grim arthouse wonder that considers the absurd social relationship between love and its inflictions. With his fifth feature and his first in English, Greek writer-director Yorgos Lanthimos examines another set of surreal social rules that must be followed to the letter. Single guests of an old-fashioned hotel undergo a rigid plan to find an appropriate match, but if they remain single at the end of their 45 days, they’re turned into an animal. Watching Lanthimos’ characters suffer existentially and sometimes physically under his application of strange rules and decorum recalls the very best of Luis Buñuel, except far more accessible on an emotional level.

Lanthimos and his frequent co-writer Efthimis Filippou construct a meticulous world in which love and relationships are scrutinized and regimented by a strict set of codes, and in which the individual and their desires are supplanted, all by extreme administrations. There’s no amount of magic or fantasy making these rules come true, nor does this dystopian world take place in a futuristic landscape. The Lobster takes place here and now, but exists under an increasingly elaborate set of procedures through which people are meant to find the designated definition for happiness. Early on, we learn freedom is given only to those in a (gay or hetero) partnership; later, we find out this status is enforced by the police. Happiness looks like quiet, inexpressive acceptance and inflexibility—bland couples moving about a modest consumer metropolis. Should a split occur, or one member of the couple die suddenly, the single party must visit a resort designed to establish pairings, or else find themselves subject to animal reclassification through (as hinted) surgery.

David (Colin Farrell), who was divorced just days earlier, arrives at the resort’s hotel with his brother Bob, who failed to find a partner and was turned into a dog. (Played by pups named Jaro and Ryac, the dog-actors won Cannes’ prestigious “Palm Dog Award.”) During an admittance interview, David is asked what animal he would like to become should he fail to couple, and he chooses a lobster. Most people choose a dog. But David’s choice remains Kafkaesque, the lobster being an undersea cousin to the cockroach. His reasons for choosing a lobster are far more telling, however: lobsters live up to 100 years and remain fertile for their entire lifespan. The hotel manager (Olivia Colman) explains that, should he not find a match and be turned into a lobster, he must then pair with another lobster. Mixed animal pairings, such as a penguin and a wolf, “would be absurd,” she says.

David (Colin Farrell), who was divorced just days earlier, arrives at the resort’s hotel with his brother Bob, who failed to find a partner and was turned into a dog. (Played by pups named Jaro and Ryac, the dog-actors won Cannes’ prestigious “Palm Dog Award.”) During an admittance interview, David is asked what animal he would like to become should he fail to couple, and he chooses a lobster. Most people choose a dog. But David’s choice remains Kafkaesque, the lobster being an undersea cousin to the cockroach. His reasons for choosing a lobster are far more telling, however: lobsters live up to 100 years and remain fertile for their entire lifespan. The hotel manager (Olivia Colman) explains that, should he not find a match and be turned into a lobster, he must then pair with another lobster. Mixed animal pairings, such as a penguin and a wolf, “would be absurd,” she says.

When his time at the hotel begins, he’s instructed not to masturbate; instead, a torturous motivation is applied when the maid (Ariane Labed) grinds on him for a brief time— a further incentive for David to find a mate. The initial moments in the hotel may be hysterical and bizarre, but in true Lanthimos form, they grow more and more disturbing. Staged performances of how, within a couple, you don’t have to worry about rape or choking to death, demonstrate the importance of “two is better than one.” New couples are announced and applauded and, after a two-week trial period, and another two weeks alone on a small yacht, a couple may go back into the world. If there’s arguing between the couple, resort management provides a child on which the couple can focus their energies. “That usually helps,” the hotel manager adds. As for recreation, the singles are taken into the woods, supplied dart guns, and asked to hunt loners—single people who have escaped this system of coupling. Each loner darted earns you an extra day at the resort.

But, as David learns, later on, the loners (led by a stony Léa Seydoux), have their own set of rules: You can masturbate wherever you want, but you cannot flirt, kiss, or have sex with others. You may dance, but only alone and to electronic music. And you must dig your own grave, just in case. In the meantime, David befriends two other men at the hotel, one with a limp (Ben Whishaw) and one with a lisp (John C. Reilly). Their respective “defining characteristic” sum these men up, insomuch that a woman without a limp or a lisp would be an inappropriate match. When Whishaw’s character eyes a young woman (Jessica Barden) prone to nosebleeds, he begins smashing his face when she’s not looking, if only to appear that he, too, suffers from the same malady. David tries something similar with a sadistic, cold-hearted patron (Angeliki Papoulia), who has remained there for months by her skill for hunting loners, with appalling results. Before long, David escapes to the loner forest, where he meets a woman (Rachel Weisz) who happens to have his defining characteristic—short-sightedness. Under loner law, their love is forbidden, and so they develop a system of codes and hand signals to communicate and arrange lovemaking.

Lanthimos champions performances that ring with Orwellian self-modulation on the outside, longing on the inside. Farrell’s restrained performance is unlike anything the actor has ever accomplished. Normally expressive and unhinged in titles like In Bruges, Cassandra’s Dream, or Seven Psychopaths, he’s asked to bury those expressive talents under his frumpy, tempered exterior in The Lobster. Take note of how Farrell’s character seems to yearn for something more, yet we see him hold back his desires and instincts to adhere to the severe procedures he’s been given. Small inflections in his otherwise monotone voice show David growing excited or nervous. It’s a careful, brilliant turn. Weisz provides narration to The Lobster’s first two-thirds, read aloud from her character’s diary with internal frankness, and further evidence that she craves feeling as well.

Throughout the film, the actors are required to deliver dialogue with an openness that seems to exist only to establish their adherence to the rules; underneath, many of them want something more but cannot openly say the words. At the same time, there are those desperate to find a mate, such as Ashley Jensen’s character, a woman who offers biscuits or sexual favors to David, and then promises to jump to her death before being turned into an animal. The outcome is far more disturbing. Also disturbing is the final scene, after Weisz’s character has been unexpectedly blinded. David is faced with maintaining their relationship. Should he blind himself, too? After all, it’s not as though he needs to assimilate for the resort. He has a choice. And so, we must ask, should he blind himself out of love? The question of whether he follows through lingers afterward, and either option leads to satisfying conclusion and commentary, prompting the viewer to define love.

Similar systems of behavior have guided Lanthimos’ work. Consider his Oscar-nominated Dogtooth (2009), in which three isolated teens must follow the bizarre rules of their overprotective parents. Or 2012’s Alps, about people who run a business where they impersonate their clients’ recently deceased loved ones to make the grieving process easier. His surreal setups are unique in today’s cinema, explored to their fullest degree, and finally setting themselves apart as high cinematic art. His presentation is deliberately paced and deceptively reserved; nevertheless, there’s a tragically romantic quality to The Lobster as well. Shooting in Dublin, cinematographer Thimios Bakatakis captures ever-present overcast skies and its muted lighting, echoed by Sarah Blenkinsop’s plain and drab outfits worn by the cast. Every character feels encased by their clothing and environment on top of their social structure. The soundtrack—heavy with strings by Strauss, Stravinsky, and Beethoven—adds a layer of melancholy and, in some cases, horror to the proceedings.

After The Lobster is over, we must go back and think about the opening, pre-title sequence, where a woman (Jacqueline Abrahams) drives through a countryside, agitated to no end, until she stops suddenly, gets out of her car, and shoots a donkey in the head. Another donkey nearby strolls over to look at the dead one. We feel a little sad for the survivor. The woman goes back to her car. What to make of this scene that is never referenced throughout the remaining two-hour runtime? Perhaps the victimized donkey was the woman’s ex-lover, who, after moving on, failed to find someone else as a human, and so became a donkey, and eventually found a new donkey-lover. Jealous, the woman has just killed her ex. It’s a wonderful moment that horrifies at the same time, in a film writhing with wonderful moments that horrify. And because of this, our initial curiosity requires that we go back and remember it, applying the progression of rules we have learned throughout.

After The Lobster is over, we must go back and think about the opening, pre-title sequence, where a woman (Jacqueline Abrahams) drives through a countryside, agitated to no end, until she stops suddenly, gets out of her car, and shoots a donkey in the head. Another donkey nearby strolls over to look at the dead one. We feel a little sad for the survivor. The woman goes back to her car. What to make of this scene that is never referenced throughout the remaining two-hour runtime? Perhaps the victimized donkey was the woman’s ex-lover, who, after moving on, failed to find someone else as a human, and so became a donkey, and eventually found a new donkey-lover. Jealous, the woman has just killed her ex. It’s a wonderful moment that horrifies at the same time, in a film writhing with wonderful moments that horrify. And because of this, our initial curiosity requires that we go back and remember it, applying the progression of rules we have learned throughout.

Much of The Lobster is like that, where we must remember the moment when a rule was explained and reference it later. Lanthimos doesn’t make his film impenetrable, but he doesn’t make it easy on the viewer either. All the while, we laugh at the awkward (sometimes excruciatingly so) interactions between people, or the way Lanthimos juxtaposes two humorous ideas into a hilarious one—such as the loner dance party where, in the woods at night, loners dance to electronic music in proximity to one another, but also each loner wears their own earbuds. Together in their aloneness. It makes the scene where Farrell and Weisz’s characters try to synchronize all the more touching. Besides being a surreal exploration and allegory on modern love, The Lobster is also tender. That the film blends the disparate ideas of surrealism and genuine romance is something rare indeed, ranking it with the likes of Charlie Kaufman or Spike Jonze. And like the films of those American directors, this one stands as a singular work of art that will demand audiences return to its dark, affecting, mysterious, and often hilarious assessment of love.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review