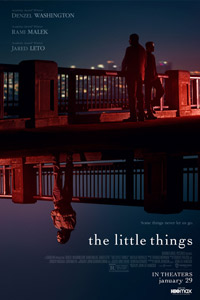

The Little Things

By Brian Eggert |

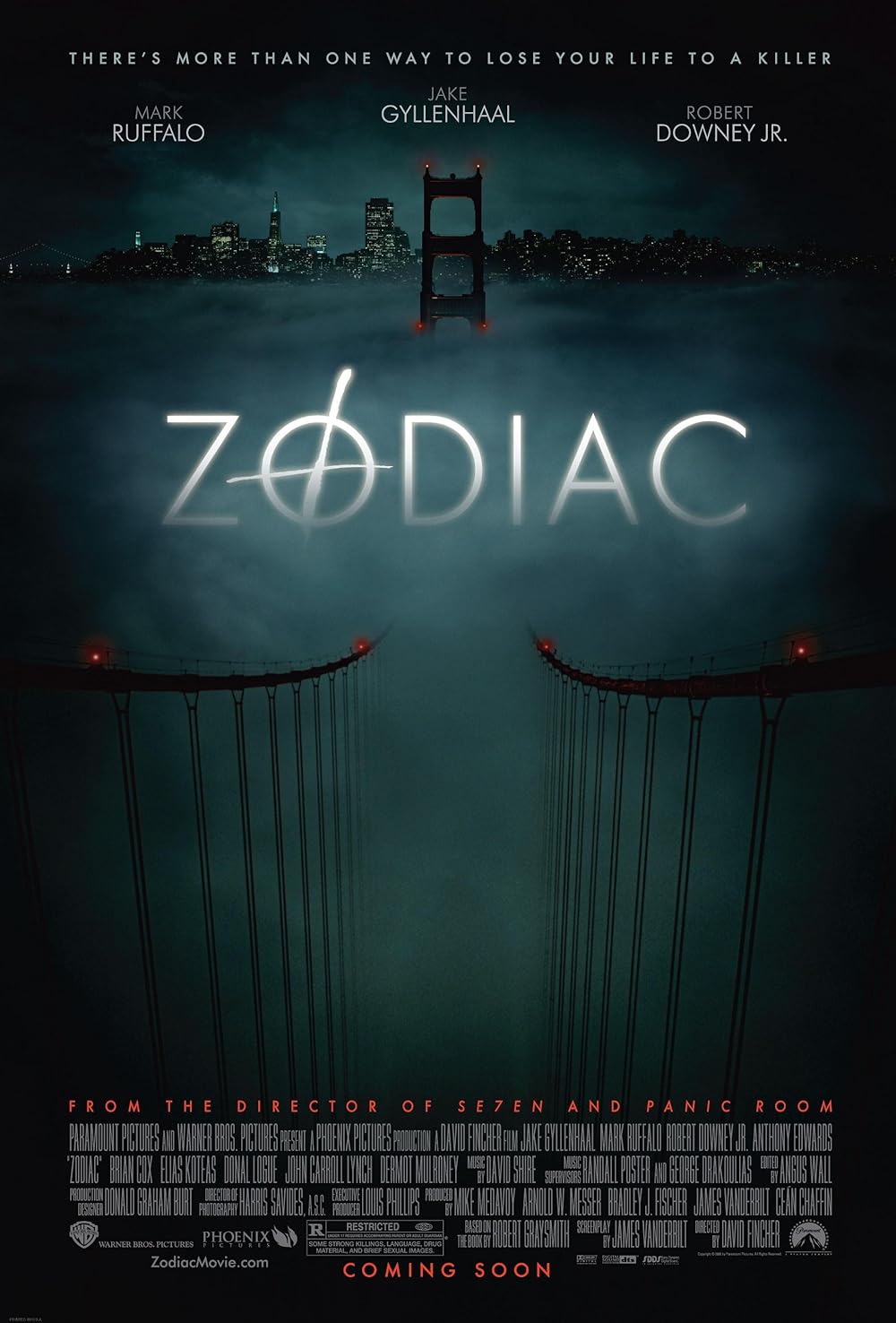

The Little Things opens with a familiar scene. A young woman drives on a highway at night, singing along with the blaring radio, unaware that a man has marked her as prey. It’s an identical shot to one in The Silence of the Lambs (1991), in which Brooke Smith sings Tom Petty’s “American Girl,” a nod at the Americanness of both the victim and serial killers. In this film, Sofia Vassilieva sings The B-52s “Roam,” perhaps winking at the killer’s profile as someone who stalks his victims wherever he may find them. It’s an old-fashioned thriller in that way, the sort that used to be commonplace in 1990s cinema—stuff like Se7en (1995), Kiss the Girls (1997), and The Bone Collector (1999), where obsessed detectives examine gristly murders and eventually catch their man. Only later did David Fincher turn the genre on its head in Zodiac (2007), a sprawling three-hour unsolved mystery. John Lee Hancock, the writer and director of The Little Things, wants it both ways. He wants a throwback to the heyday of entertaining 1990s serial killer movies, even as he edges toward something lacking closure.

Set in the year 1990, Hancock’s movie follows Joe Deacon (Denzel Washington), a deputy sheriff in Kern County, California. Not so long ago, he worked homicides in Los Angeles, but one bad case left him divorced and with a triple bypass, so now Deacon, known as Deke, works small-town crime. When he’s asked to return to L.A. to pick up evidence for a case, he’s brought into an investigation overseen by his successor, Det. Jim Baxter (Rami Malek). The case is familiar to the one that put Deke over the edge five years earlier. He finds himself taking vacation days from his “dep” position to sleuth alongside Baxter, a family man who likes the media spotlight. Baxter is a mirror reflection of Deke, obsessive and determined. Despite the warnings of his colleagues, Captain Carl Farris (Terry Kinney) and Detective Sal Rizoli (Chris Bauer), he continues working with the toxic former detective. And while Washington elevates his role’s absurdity out of sheer persona, Malek’s presence can’t help but implant our undue suspicion that he’s the killer.

Third in the movie’s trio of Oscar-winning actors is Jared Leo, who plays the main suspect, a weirdo named Albert Sparma. With a lumbering walk, black eyes, and a look vaguely reminiscent of Charles Manson (he keeps a copy of Helter Skelter on his bookshelf), Sparma fits the profile—he even becomes aroused by crime scene photos during a memorable interrogation scene. But Deke and Baxter lack any substantial evidence against Sparma, leading to a prolonged tailing sequence set to Peggy March’s “I Will Follow Him”—one of those on-the-nose soundtrack choices that feels too cute for the material. Overacting every moment in a way that has become typical in his roles, Leto proves unnerving, though his acting takes us out of each scene. By the last third, when the investigation reaches a certain point that finds Baxter getting into a car with Sparma, everyone’s behavior goes off the rails, and we feel Hancock’s screenwriting calling the shots, not the characters.

Alas, Hancock doesn’t have the delicate touch or tonal control required to balance the fine line between a serial killer movie and a character study that he hopes to walk with The Little Things. This is the director of The Blind Side (2009), after all; subtlety isn’t in his playbook. What we get instead are awkward scenes in which Deacon talks to corpses, sometimes real, sometimes imagined, saying things like, “You can talk to me. I’m the only friend you got.” Nothing much comes of that. It’s not a sixth sense or intuition, like with Thomas Harris’ detective Will Graham; it’s just a rogue aspect to the character. Somewhere in the movie is an underdeveloped theme about Deke representing what Baxter will become if he doesn’t stop obsessing over the case. Still, Deke hasn’t exactly gained perspective, given how quickly he leaps back into the role of L.A. detective, despite his past mistakes. It feels like Hancock has all the elements in place for an effective drama about strung out professionals, but he’s too interested in the mechanics of a serial killer movie to build the detectives into believable, three-dimensional characters.

Alas, Hancock doesn’t have the delicate touch or tonal control required to balance the fine line between a serial killer movie and a character study that he hopes to walk with The Little Things. This is the director of The Blind Side (2009), after all; subtlety isn’t in his playbook. What we get instead are awkward scenes in which Deacon talks to corpses, sometimes real, sometimes imagined, saying things like, “You can talk to me. I’m the only friend you got.” Nothing much comes of that. It’s not a sixth sense or intuition, like with Thomas Harris’ detective Will Graham; it’s just a rogue aspect to the character. Somewhere in the movie is an underdeveloped theme about Deke representing what Baxter will become if he doesn’t stop obsessing over the case. Still, Deke hasn’t exactly gained perspective, given how quickly he leaps back into the role of L.A. detective, despite his past mistakes. It feels like Hancock has all the elements in place for an effective drama about strung out professionals, but he’s too interested in the mechanics of a serial killer movie to build the detectives into believable, three-dimensional characters.

The Little Things also holds the rare distinction of being the most distractingly edited film in recent memory. Although cinematographer John Schwartzman captures its many night scenes with clarity and atmosphere worthy of an L.A. noir, editor Robert Frazen scrambles in jarring, inelegant cuts that feel as though they’re trying to create momentum or tension but instead feel forced. Watch an otherwise calm scene where Deke visits Baxter at home; they share breakfast, and Deke meets Baxter’s family. Rather than a calm master shot that shows them all together, every gesture, every line of dialogue receives a cut, often from different perspectives, as though Hancock ordered Frazen not to waste one angle from the considerable coverage. Several scenes play out like this, distracting the viewer with a sharpness that doesn’t fit the moment.

Fans of Washington or the genre may find The Little Things passable, but it’s the kind of movie that finds you saying things like, “It would have been better if…” In other words, it’s hardly satisfying. By the time Thomas Newman’s score offers optimistic notes over the last shot of Washington and his dog living happily ever after—an odd choice, given what happens in the end—it becomes apparent that Hancock didn’t have a clear vision of the end product. Strange, considering he wrote the initial version in 1993 and spent nearly three decades trying to get it made. It feels that way, too—as though Hancock wanted to try something different than the detectives-catch-the-killer scenario of The Silence of the Lambs. But in the meantime, other pictures, such as Zodiac, have done what Hancock was trying to do with his original script, only they did it better and with characters who behave in emotionally believable ways. Unfortunately, with The Little Things, Hancock seems to be trying to subvert the expectations of 1990s audiences, not today’s, leaving the movie’s conceit to feel underdeveloped.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review