The Little Prince

By Brian Eggert |

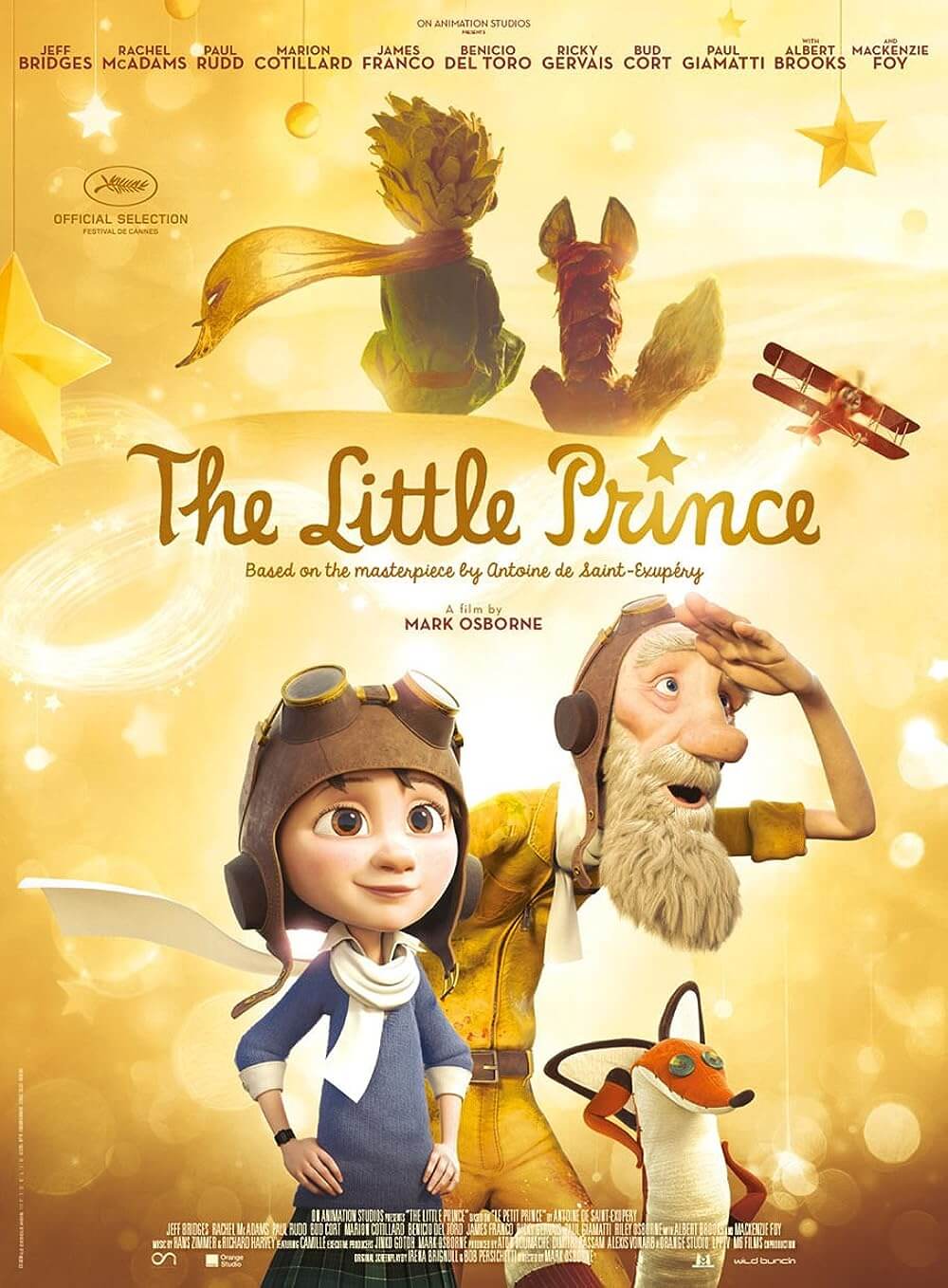

After earning universal praise around the rest of our planet during its original 2015 release, The Little Prince debuted in the U.S. on Netflix in 2016. This modern adaptation of Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s classic 1943 storybook follows various adaptations in the form of graphic novels, a ballet, musicals, an opera, feature films, an animated series, and a stage theatre production—all based on the wildly popular text. Indeed, Saint-Exupery’s novella has been adapted dozens of times before, but never quite as satisfying as this. The French story arrives in the English-language with a phenomenal voice cast of recognizable celebrities and a diverse visual presentation consisting of animation styles that fill our eyes with wonder. American audiences may not have the opportunity to see The Little Prince at their local moviehouse, nor even an arthouse theater, but in no way does that speak to the quality or craftsmanship put into the production.

What happened behind-the-scenes around the book and its adaptation remains almost as interesting as the film itself. For example, Saint-Exupery based his story on his own 1935 crash-landing in the Saharan desert alongside navigator André Prévot, during their race to Saigon. The two men barely survived their four-day ordeal in the desert heat before being rescued by a Bedouin passer-by. In his story, Saint-Exupery’s crashed pilot meets a young boy, the titular prince, who claims to be an alien—the sole inhabitant of a distant asteroid, number B-612. The yellow-haired boy fills the pilot’s ear with tales of his travels to a series of asteroids, each occupied by a sole resident. After several days of friendship in the desert, the boy makes a deal with a snake to end his life so his spirit can float back into space and return home, assuring the pilot that he need only look at the stars and remember the Prince. Coincidentally, just a year after his book was published, Saint-Exupery vanished after heading out from a Corsican airbase in his P-38 fighter plane, and many compared his disappearance to that of his pilot character. As recently as 2003, evidence of the author’s crash has washed ashore on an island south of Marseille.

Most fascinating, and indeed perplexing, is the film’s release, especially the truncated stateside distribution. French producer Dimitri Rassam independently backed the film for $80 million, hiring Kung Fu Panda director Mark Osborne to direct back in 2010. Over the next five years, Osborne developed a revisionist take on Saint-Exupery’s book, framing the entire story through the modern world, where imagination has no place in our orderly, regimented life plans. When the film debuted at the Cannes Film Festival in 2015, it received stellar reviews and went on to earn over $90 million in various world markets—though the U.S. was not among them. Paramount Pictures was initially set to handle distribution in the states, with a theatrical release date set for March 2016. However, just a few weeks before the film’s release, Paramount announced they would no longer be distributing the film into theaters. Quite disgracefully, The Little Prince finally debuted on Netflix the following August, bearing the heading “A Netflix Original Film”.

Set that aside for a moment. Screenwriters Irena Brignull and Bob Persichetti follow Osborne’s screen story, which constructs an elaborate framing device around Saint-Exupery’s tale. We follow a handful of new characters living in a contemporary world—a gray, down-to-business suburban configuration that looks like something out of Jacques Tati’s Playtime (1967). Moreover, Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985) comes to mind when the main character, an unnamed child known only as Little Girl (voiced by Mackenzie Foy), must endure the regimented “life plan” designed by her obsessive single mom (Rachel McAdams). The Little Girl and her mother have just moved so she can attend a top school called “Werth Academy” in the fall, and she has just the summer months to prepare for the rest of her life. Left home each day, she’s expected to follow a tightly wound study schedule broken up into brief increments. Instead, she’s distracted by her old-coot-of-a-neighbor, an Aviator (Jeff Bridges) with a long, craggily beard and rambunctious temperament.

Through the course the story, the Aviator awakes the girl’s mind to imagination, to the simple joys of Nature and playing, all through the prism of a story he’s written, which follows Saint-Exupery’s book. Osborne separates the two strains visually, telling the story of the Little Girl and Aviator with today’s standard computer-generated animation, whereas the storybook segments are rendered with a stop-motion animation that has a fantastic tangible quality approaching Henry Selick’s Coraline (2009), and closely resembles the book’s original artwork. The storybook scenes are wondrous, introducing us to the author’s original characters: The Little Prince himself is voiced by Riley Osborne, the director’s son; we also meet his demanding Rose (Marion Cotillard); a desert snake (Benicio Del Toro); the Prince’s dear friend, the Fox (James Franco); the Conceited Man (Ricky Gervais) who yearns for applause, even if it’s undeserved; the King (Bud Court) who sits on a throne in a vacant world; and Albert Brooks proves intimidating in his voicework as the Businessman, who wants to own the stars. Meanwhile, songs by French singer Camille, alongside classics by Charles Trenet, are accompanied by a delicate score from composers Hans Zimmer and Richard Harvey, bringing the proceedings to musical life.

I loved the way The Little Prince brings the original story to life in creative ways, and yet, because the original book was too short to fill a full-length feature, expands with an equally inspired story that relates the material to modern viewers. Although it’s not a purist’s adaptation, it’s inspired nonetheless. The final act ventures into a realm of pure imagination when the Little Girl, determined to save the dying Aviator, takes off in his plane with her rather adorable sidekick, a stuffed animal fox. They soon find the Little Prince all grown up (and voiced by Paul Rudd). Now a cog in a productive world run by the Businessman, the Prince has survived by trying to conform to The Man. Images of a cold office metropolis frighten, particularly the thin, gray-skinned employees who nod and applaud every reduction of creativity. The film’s most inspired, enduring theme remains the embrace of creativity and fantasy, and how the less we accept that reality should be a dull, orderly existence, the more likely we will find joy and love. If the unjust, curtailed release of The Little Prince wasn’t enough to seek it out and support it, then at least a message about the importance of dreams, play, and imagination should inspire you to see this wonderful film.

When family-appropriate animated features are almost guaranteed huge box-office numbers, it makes no sense that Paramount dumped The Little Prince to Netflix. Aside from the occasional presence of French writing, the film contains no major French signifiers and nothing that would prevent U.S. viewers from losing themselves in the story. One can only speculate as to why Paramount backed out, but this critic suspects the studio couldn’t figure out how to advertise a film with this much imagination—a film that didn’t fit the often simplistic formula of most children’s fare these days, and may challenge viewers from time to time. Rather than take a cue from Pixar’s promotional team and their excellent track record of marketing atypical stories, the studio abandoned the film to Netflix and robbed countless families from being able to experience Osborne’s excellent, relevant adaptation in theaters. One can only hope families take a chance and add this title to their watchlists. So few animated films try anything outside of the realm of normalcy; fortunately, Osborne’s film realizes normalcy is, well, boring. Only the unexpected and astonishing can ignite our imaginations, and The Little Prince has those qualities to spare.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review