The Little Mermaid

By Brian Eggert |

The Little Mermaid is further proof that Disney is not in the business of adapting their classic cartoons into live-action films; they’re in the business of translating those stories into a new visual format. Adaptation involves taking existing material and changing its components to fit a new textual environment. For instance, when Baz Luhrmann adapted Romeo and Juliet in 1996, he didn’t present the material as written by Shakespeare, which took place in sixteenth-century Italy. Rather, he reconfigured the play in a contemporary setting for modern sensibilities. But Disney and director Rob Marshall have no interest in tampering with the brand integrity of their 1989 animated feature. In another story of star-crossed lovers, the major changes here consist of a few added songs, a few omissions, a few fleshed-out scenes, and a presentation driven by new technologies—namely, the CGI spectacle of today’s blockbuster. The Little Mermaid and all of Disney’s recent remakes barely qualify as adaptations then; they should be known as live-action translations. Like a book translation from one language to another, Disney maintains the overall structure of the original, adding mild poetic license where the translator sees it as appropriate. The movie is not so much a new vision as a shift from one visual language to another, from hand-drawn animation to computer animation and live-action footage.

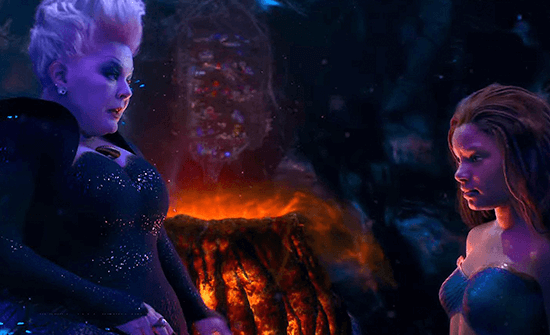

Fortunately, the new version of The Little Mermaid is one of Disney’s best translations, which is not a high bar to reach. It rests on the narrative’s strength and the charm of its lead, Halle Bailey, who gives a delightful, star-making performance and represents the sole actor to disappear into her role. Although the cast features familiar faces clearly having fun—Javier Bardem as King Triton and Melissa McCarthy as Ursula the octopoid sea witch—these big-name performers never give up their celebrity persona for their characters. Unfortunately, neither do the other lesser-known performers entirely inhabit their roles. Instead, it’s as though everyone’s playing dress-up. But that’s not an altogether negative quality. After all, the history of adaptation, particularly on stage with revivals of well-known plays and musicals, celebrates the unspoken agreement between performer and audience, who agree that everyone on stage is merely retelling a story that has been told many times before (think of Orson Welles setting Macbeth on a fictional Caribbean island in his famous 1936 production). And sure enough, there’s a particular delight in watching these actors perform the nostalgic material.

The problem with The Little Mermaid and Disney’s other translations is that too little work has been done to alter the material and make it relevant or even artistically vital compared to the originals. The screenwriter David Magee has no freedom to maneuver. He was no doubt beholden to his Disney overlords and the source material—which is to say, Disney’s earlier film and not Hans Christian Andersen’s dark fairy tale (where Ariel’s search for love ends in suicide). So, things play out as you might expect, with the rebellious young Ariel (Bailey) yearning to be part of the human world. At first sight, she falls in love with a bland prince named Eric (Jonah Hauer-King), but her father finds out and forbids her from leaving their underwater home. Ariel then resorts to desperate measures, striking a deal with Ursula to acquire her humanity in exchange for her voice—the very thing that Eric could use to identify the woman who saved him from a shipwreck. Voiceless, Ariel arrives in the human world and charms Eric, only to be interrupted by Ursula’s evil plan. There are surprises here, but it’s all reasonably enchanting.

Among the minor changes to the story, Ursula alters her potion so that Ariel doesn’t remember needing “true love’s kiss” from Eric by the third day, which nominally amplifies the stakes for her photorealistic CGI animal friends: the singing crab Sebastian (Daveed Diggs), the childlike fish Flounder (Jacob Tremblay), and the scatterbrained seabird Scuttle (Awkwafina). The production makes an effort toward inclusive casting, with Ariel’s multiracial mermaid sisters suggesting Triton has been fertilizing eggs around the globe. The screenplay also adds a human equivalent to Triton on land, with Noma Dumezweni playing Queen Selina, Eric’s mother, who doesn’t trust sea people as much as Triton doesn’t trust humans. Most welcome is casting a Black actor in the lead role, marking only the second Black princess in a Disney movie since The Princess and the Frog (2009). Bailey’s wide-eyed presence brings Ariel to life, especially in scenes where her character is voiceless and must rely entirely on body language and facial expressions to communicate.

Among the minor changes to the story, Ursula alters her potion so that Ariel doesn’t remember needing “true love’s kiss” from Eric by the third day, which nominally amplifies the stakes for her photorealistic CGI animal friends: the singing crab Sebastian (Daveed Diggs), the childlike fish Flounder (Jacob Tremblay), and the scatterbrained seabird Scuttle (Awkwafina). The production makes an effort toward inclusive casting, with Ariel’s multiracial mermaid sisters suggesting Triton has been fertilizing eggs around the globe. The screenplay also adds a human equivalent to Triton on land, with Noma Dumezweni playing Queen Selina, Eric’s mother, who doesn’t trust sea people as much as Triton doesn’t trust humans. Most welcome is casting a Black actor in the lead role, marking only the second Black princess in a Disney movie since The Princess and the Frog (2009). Bailey’s wide-eyed presence brings Ariel to life, especially in scenes where her character is voiceless and must rely entirely on body language and facial expressions to communicate.

Less emotive are the musical numbers and their visual treatment. The staging of famous sequences, especially the Oscar-winning song “Under the Sea,” suffers from flatness. The filmmakers seem to have taken the potency of the original versions, trimmed their lyrics, and dialed their levels down a few notches, rendering them less energetic (a common problem with Disney’s live-action translations). Worse, the production hired Lin-Manuel Miranda to add two new songs, including a dull “I Want” number for Eric and a catchy but ill-fitting rap called “The Scuttlebutt” for Awkwafina’s character, and both lack the magic of Alan Menken’s songs. The new movie also removes the subplot about Sebastian evading a stereotypical French chef in Eric’s palace, along with his still-disturbing song about preparing fish (“I pull out what’s inside, and I serve it up fried”). But part of why everything feels so muted is because the animators rob characters like Sebastian—who in 1989 had large, expressive eyes and a mouthful of teeth—into realistic-looking animals. With his lifeless crustacean eyes and minuscule mouth, he’s not so inviting. Then again, a photorealistic crab with expressive features might have been nightmarish.

Despite its reported budget of $250 million, much of The Little Mermaid looks unconvincing, particularly the underwater scenes. When shafts of light penetrate the water, it seems like a cheap video game effect. The non-speaking fish characters look real enough, as does Ariel’s interaction with a shark. But when the merpeople move, their hair moves artificially, recalling early experiments with motion capture in the 2000s. The effects around Ursula stand out as the production’s worst—it often looks like McCarthy’s face has been digitally superimposed onto an animated head and body. Luckily, the actor’s voice, which occasionally sounds like Ruth Gordon in Rosemary’s Baby (1968), overcomes the visual incongruities. Elsewhere, almost as a rule, everything looks better when Ariel explores the surface world. Removed from the digital haze, Bailey’s sprightly beauty, and Marshall’s placement of her in recreations of iconic scenes from the 1989 film, make it clear why Disney cast her. Cinematographer Dion Beebe deploys luminous sunsets to frame Ariel, and the effect is often stunning. Art Malik, playing Eric’s butler Grimsby and serving as his moral compass, also lends a great deal of humanity to the land scenes.

If the 1989 version was slyly subversive for having a protagonist who defies her patriarchal father to pursue her interests, the new version overemphasizes the point by underlining Ariel’s status as a “voiceless” character who earns agency when people start listening to her. While a worthy theme, Disney once again turns lessons that should be readable and open to interpretation into unmissable statements in the dialogue. Regardless of the obvious writing and often ugly digital presentation, the film’s secret weapon is Bailey, and we follow her through the familiar story, recalling identical moments from the original animated movie with a certain reluctant yet undeniably warm and effective nostalgia. Marshall—who has been on the Disney retread bandwagon with Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides (2011) and Mary Poppins Returns (2018)—ultimately delivers a mixed bag. The translation boasts moments of great music and wonder, but at times it’s lifeless and contains off-putting talking animal characters, which is less an issue with Marshall’s execution than the general concept of a live-action remake of Disney’s adaptation of Andersen’s book. Even so, it’s better than most of these Disney cash grabs and worth seeing to witness the emergence of Bailey as a new star.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review