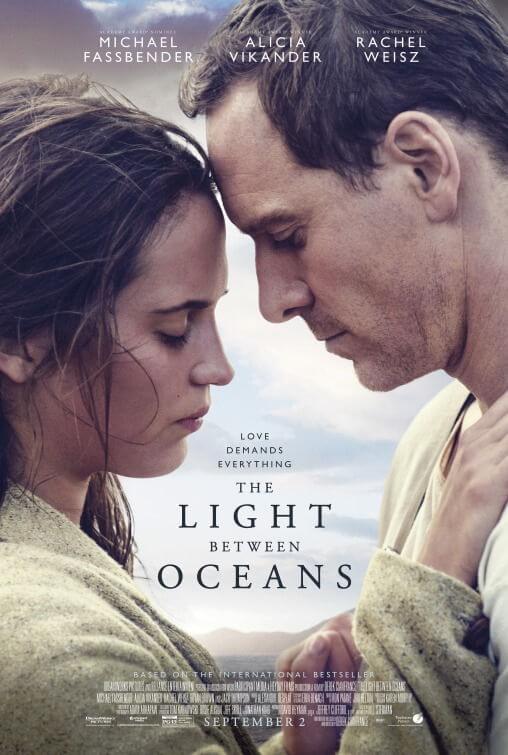

The Light Between Oceans

By Brian Eggert |

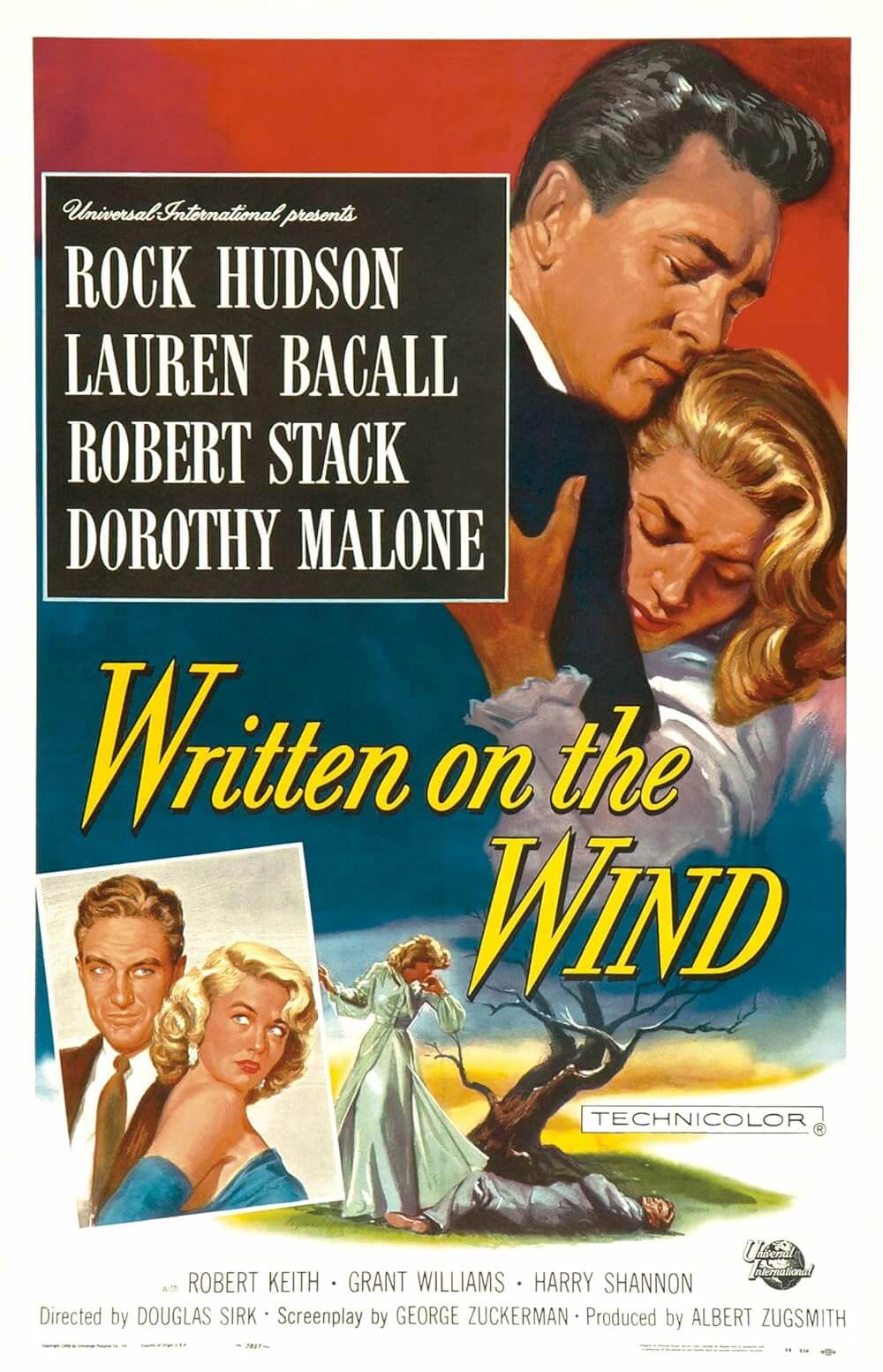

Melodrama carries an undue stigma. Many critics use the word more often as a pejorative than an adjective. The derogatory “melodramatic” suggests overwrought and exaggerated emotion, qualities that represent an unpopular theatricality in today’s realism-obsessed culture. Whereas melodrama once represented the height of expressive cinema with filmmakers like Douglas Sirk (Written on the Wind, 1956), the mode has since become unfashionable and disliked by most, even though its influence can be evidenced everywhere from the Harry Potter franchise to Nicholas Sparks to Todd Haynes’ Carol (2015). The word itself means a combination of melody and drama; not in the musical sense, but in the way the narrative grows with gradual emotional crescendos.

The Light Between Oceans has been widely described as a melodrama in the disapproving sense. Richard Roeper at the Chicago Sun-Times dismissed it as “soap opera material,” and David Edelstein of New York Magazine said it “[seems] like an inchoate hybrid of melodrama and psychodrama.” Most critics agree, this is a gorgeously shot, beautifully acted motion picture, but they take issue with the story’s trajectory and logic, whereas melodrama requires that characters and their audience become so wrapped up in the proceedings that they lose control of their emotions. Without emotions sometimes flying wildly out of control, it would cease to be a melodrama. Questions of morals and sound reasoning have no place in a story like this.

Author M.L. Stedman’s best-selling novel debuted in 2012, and director Derek Cianfrance, helmer of Blue Valentine (2010) and The Place Beyond the Pines (2012), adapted the material himself. The story begins around 1918 when World War I veteran Tom Sherbourne (Michael Fassbender) takes a job as a lighthouse keeper on an island called Janus, just off the western coast of Australia. Quiet and inward, Tom looks forward to the long periods of solitude required for his new station, as he’s suffering from soldier’s guilt and shell shock. Janus provides him with enough tasks to keep himself busy while he ruminates. He’s isolated amidst hundreds of miles of powerful ocean on all sides, omnipresent sunrises and sunsets, storms, and an ever-blowing wind—all of which might be exhausting if they weren’t so stunning to behold.

In one of his infrequent trips to the mainland, Tom finds himself on a picnic with Isabel (Alicia Vikander), a young woman with whom he shares a series of letters in the coming months, compelling him to talk about his feelings for the first time in a long time. Soon they are married, and Isabel joins him on Janus. The scenes of their wedding and early marriage are simple, shot through sun-drenched, soft-lit lensing by cinematographer Adam Arkapaw, who roves around these lovers like a Terrence Malick picture. Vikander smiles with happiness that suggests she’ll burst into tears at any moment, and it becomes clear that she’s falling in love. In fact, the two leads fell for each other while making this film.

Their serene life on Janus becomes troubled after Isabel suffers two miscarriages. This demanding bit of land in the middle of the ocean hardly seems capable of supporting life, much less a family. Nevertheless, just after burying their second loss, a dinghy washes ashore containing a dead man and a crying infant girl. Isabel sees it as a sign. Tom insists they should report it. She convinces him to hide the man’s body and raise the child as their own, and because no one knows about the second miscarriage, no one will suspect what happened. This may seem instantly wrong to many viewers; however, the isolation and emotional fragility of both Tom and Isabel forms the perfect concoction to justify their choice. Only later, in the following months and years as they raise their newfound child, whom they’ve named Lucy, does Tom alone begin to act on his guilt and seek out the biological mother, Hannah (Rachel Weisz).

The plot turns on a few predictable notes, such as when Tom takes a unique baby rattle from the dinghy and keeps it; of course, this will be the key to their exposure later in the film. And the epilogue feels oddly detached from what came before. But scenes on the mainland prove revealing. Removed from the moral justifications and safety of seclusion, Tom finds it impossible to pretend, especially when faced with Hannah, and so he acts out in troubling ways to relieve his guilt. Fassbender has carried tormented roles like this one before, such as in Shame (2009) or Frank (2014), where his character denies the reality of what he feels by escaping, or simply carrying it. He excels at brooding and is simply wonderful here. Weisz portrays an equally wounded character who, when reunited with her baby, must achingly endure Lucy’s pleas for her “real mommy”—meaning Isabel. As for Vikander, she demonstrates that her recent Oscar win wasn’t just a fluke. Indeed, the performances bring The Light Between the Oceans to life, lending every scene an emotional lucidity.

By the time Cianfrance tests our empathy by introducing Hanna, we have already bonded to Tom and Isabel, and their loss becomes a tragic one that will fill the viewer’s eyes with tears by the final tender moments. Cianfrance’s entire film feels like an open wound that would heal if only the characters could stop and behave rationally, but rationality has no place in a melodrama. Their behavior does not make sense when scrutinized against logic, but the emotional heft contained within the two-hour-and-fifteen-minute runtime is inescapable and operates in absolute severity. As viewers, we come to understand their behavior, because Cianfrance isolates us on Janus to see the situation through their suffering; we see Tom and Isabel from their equally isolated and thus distorted point-of-view. Unfortunate predictabilities in the plot aside, The Light Between Oceans is melodrama in the best sense of the word, containing big emotions and requiring a corresponding level of emotional commitment.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review