The Legend of Tarzan

By Brian Eggert |

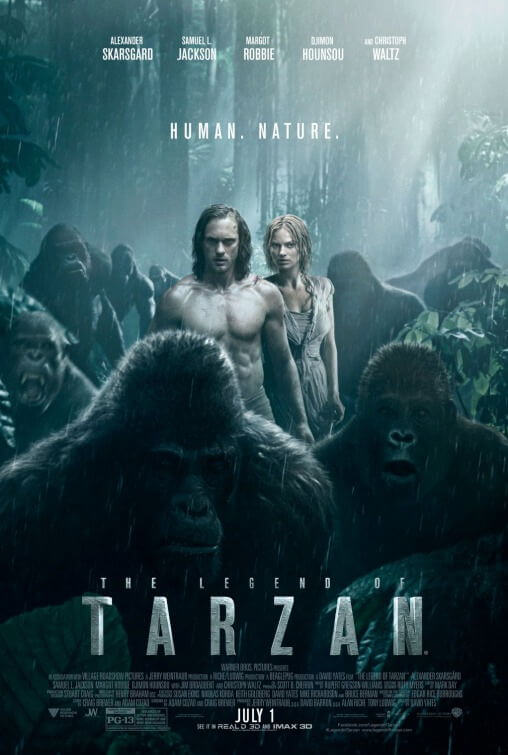

The Legend of Tarzan finds British director David Yates taking on Edgar Rice Burroughs’ iconic “ape man” in contradictory terms. Though basically following Burroughs’ classic Tarzan archetypes, the Warner Bros. release considers a more progressive look at the character in historical and social contexts, whereby the pro-colonialist perspective of the original novels is reconsidered. The film also reformats the inherent racism and sexism of the source material. And yet, even as Yates represents these issues as problematic realities of the period, he doesn’t shy away from their presence within the ingrained Tarzan formula. A reboot that feels more like a sequel, yet contains elements of an origin story, albeit a revisionist one, The Legend of Tarzan is a lot of things at once. Although, it never quite delivers Yates’ intended pitch-perfect balance of escapist jungle adventure and high-minded, socially responsible storytelling, largely because of a predictable script and subpar special FX, but mostly because it’s a major buzzkill.

Burroughs created Tarzan in 1912, and by his death in 1950, he penned twenty-four books about the fabled jungle hero. The stories followed a British orphan whose parents were shipwrecked and died in the wilds of Africa when he was a baby, leaving him to find a new family in the Mangani, a race of humanlike apes who raise him. Eventually, he marries a fair-haired American woman named Jane and becomes the vine-swing, Jane-rescuing, animal-conquering hero he’s known as today. Tarzan stories were broadcast on the radio, made into Saturday matinee serials, adapted into both live-action and animated films (MGM’s movies starring Johnny Weissmuller and Maureen O’Sullivan were the most popular), and showcased in virtually every other medium (comic books, television, cartoons, etc.). Undoubtedly a product of a colonialist vision, Burroughs wrote about a Caucasian champion whose racial superiority allowed him to tame the feral black jungle. Simply attempting to adapt this material for modern audiences is ambitious and problematic.

Without a doubt, Warner’s intention to “get it right” meant the production remained in development for well over a decade. Though various directors and story concepts came and went over the years (including one intended to replicate the tone of the Pirates of the Caribbean films), the studio finally settled on Yates, who helmed the last four installments of their Harry Potter franchise. Yates brought a politically minded weight to those films, and he does the same for The Legend of Tarzan alongside screenwriters Adam Cozad and Craig Brewer. Together, the filmmakers reconsider Burroughs’ original motivations and put them through a historical lens, adding layers of social responsibility. Although the aforementioned colonialism, racism, and sexism all have their moments in The Legend of Tarzan, each are openly acknowledged as troublesome within the self-aware writing.

The opening titles even have an air of cynicism toward the film’s late nineteenth-century setting, where “the world’s colonialists have taken it upon themselves” to conquer and slice up the Congo into various bits. Already, Tarzan feels secondary to the film’s overt themes, a quality that does not improve as the film carries on. Played by the towering Alexander Skarsgård, Tarzan first appears in England, having left his jungle home to live a dull life under his given name, John Clayton III, Fifth Earl of Greystoke and member of the House of Lords. He’s happily married to Jane (Margot Robbie), and life is such that he doesn’t embrace Tarzan-mode for nearly half the film. Rather than another origin story about taming the beast, The Legend of Tarzan turns that idea on its head, and instead is about unleashing the beast once more. This becomes easy when, after the couple travels back home to the Belgian Congo, an otherwise empowered Jane finds herself held captive by Christoph Waltz’s dastardly villain Capt. Leon Rom.

Working for Belgium’s King Leopold II, Rom intends to turn Tarzan over to a vengeful tribe (headed by Djimon Hounsou) in exchange for some diamonds to fund the King’s enslavement of the Congolese natives. In another attempt at historical responsibility, Samuel L. Jackson appears as Tarzan’s ostensible sidekick; however, instead of being a Friday-esque, Jackson plays George Washington Williams, a real-life Civil War veteran. Williams famously wrote an open letter to Leopold II about the Belgian exploitation and enslavement of the Congolese people, and the writers cleverly acknowledge that fact in the film. Still, Jackson doesn’t really act so much as embody his familiar onscreen persona, wherein he responds to every situation with varying degrees of incredulity: “Why is it people don’t ride zebras?” or “I ain’t eating no damn ant!” or “I’m not gonna lick that gorilla’s nuts!” Yes, this is actual dialogue from the film. Nevertheless, Jackson’s character also recounts his time fighting Native Americans for the U.S. government, and compares America’s genocide of native tribes to Leopold’s atrocity-laden treatment of the Congolese people.

This is all very heavy stuff for an escapist adventure, certainly heavier than Burroughs ever intended. Consider also the subplot about Jane’s miscarriage. Or the sequence in which Tarzan’s family of apes is gunned down by Rom’s hired goons. Or the shot of a train carrying mounds of blood-stained elephant tusks. More of a bummer than each of these moments is the lingering question of 800 Congolese slaves. About mid-film, Tarzan frees a few Congolese natives from Rom’s slaver train, whose engineer confesses Rom has about 800 more slaves building the railroad for Leopold’s kingdom. And yet, by the film’s conclusion, after Tarzan has saved the day (spoiler?), there’s no scene showing Rom’s 800 slaves being set free. For a film so devoted to providing its audience with one major bummer after another, this oversight remains shocking.

The production also boasts some shockingly bad CGI. Just a few months after Jon Favreau’s lovely looking The Jungle Book, there’s simply no comparison here. Some of the animals, mostly gorillas, appear photo-real in more stationary scenes, but during fast-paced action they look cheaply composed—surprising, given the film’s $180 million budget. During jungle scenes, the actors appear to be standing on a different plane of existence, the backdrops realized with green screen technology and computer animation (it won’t surprise anyone to learn the majority of this film was shot in England’s branch of Warner Bros. Studios). As for the actors themselves, Skarsgård essentially repeats his role of Eric from HBO’s True Blood, being a specimen of enormous physical power and a resting stoic temperament. He’s only required to appear moody, look fit, and swing on the occasional CGI vine. The role contains little substance. Jane doesn’t fare much better. Even if Jane refers to herself as a “damsel” with knowing contempt, it doesn’t change the fact that she is a damsel for much of the film.

Yates both embraces and defies Borroughs’ vision, and the union of these two intentions is a marriage that should be annulled. Tarzan isn’t a hero for today’s socially conscious audiences. He’s a product of a bygone era, and he demands a style of fun and escapist adventure that no longer exists today. As Captain America: Civil War and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice proved, today’s superhumans must consider the context of their actions in ways extending from moral to political, even philosophical. Trying to apply such requirements to a singular hero such as Tarzan does not work, at least not in the case of The Legend of Tarzan. It’s as though the filmmakers learned about the reality of the period in which their story takes place, and they became so disenchanted and obsessed with historical accuracy that they forgot to make an escapist adventure. This isn’t a fun blockbuster, and when it tries to be, its failures are punctuated with historical commentaries on slavery, genocide, and animal cruelty. Borroughs would be bored.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review