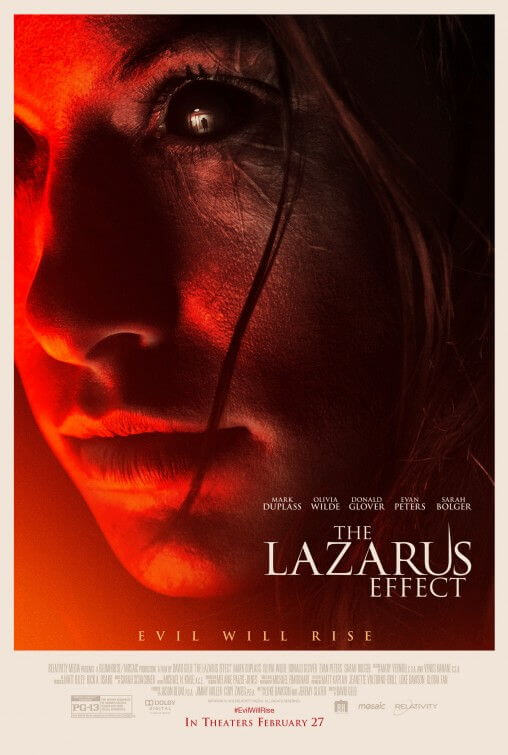

The Lazarus Effect

By Brian Eggert |

Either the young scientists hoping to resurrect the dead in The Lazarus Effect aren’t well-read, don’t watch movies, or simply remain naïve to all pop-culture warnings about the subject. Any rudimentary knowledge of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein or the classic 1931 film by James Whale will tell you that bringing flesh back from the dead results in self-aware abomination. If not one of the many adaptations of Frankenstein, then at least they should have seen Joel Schumacher’s 1990 thriller Flatliners, about medical students who seek proof of the afterlife by inducing near-death experiences (hint: things didn’t turn out well). Then again, the scientists here start out with small animals; specifically, a failed trial with a pig, and then a successful test with a dog. Maybe they should have read Stephen King’s Pet Sematary, or at least seen the 1989 movie.

Alas, the characters in director David Gelb’s first venture into horror filmmaking (Gelb is best known for the fascinating documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, from 2011) never seriously question or worry about the potential scary outcomes inherent to raising the dead. Nor are they very concerned about the moral implications of such an act. Though the film delves into scientific psychobabble at times, the screenplay by Luke Dawson and Jeremy Slater is more interested in cheap shocks and creepy imagery, as opposed to exploring even the slightest theme related to the potentially weighty scenario. This fits the requirements of Blumhouse Productions (Insidious, Paranormal Activity), a studio jealously devoted to supernatural horror of the dullest variety.

The movie takes place almost entirely in a basement research lab on the Berkeley University grounds. Frank (Mark Duplass) and his fiancée Zoe (Olivia Wilde) lead a team of scientists: Nike (Donald Glover), who has a past with Zoe; Clay (Evan Peters), the resident jokester and stoner; and Eva (Sarah Bolger), a student documentarian cataloging their research. Together, they’ve concocted a serum that was originally intended to preserve the brain after death, allowing doctors to have more time for normal resuscitation efforts. Turns out that whatever they made (a white goo) brings animals back to life after an injection to the brain and a jolt of several thousand volts. Their first successful test is on a dog, which begins to act strangely after the procedure—it’s lethargic, refuses to eat, and behaves in peculiar ways.

“This thing could go Cujo on you in a hurry!” says Clay, which tells us he’s a Stephen King reader, but that the warnings of Pet Cemetery didn’t occur to him earlier. As the resident god-fearing scientist, Zoe is more concerned that they pulled the animal back from “doggie heaven”. Before they can test again, the university somehow learns about their activities and, along with a pharmaceutical company seizing their data, shuts them down. Of course, everyone agrees to a last-minute experiment that goes terribly wrong and electrocutes Zoe, prompting Frank(enstein) to test their procedure to get her back. When Zoe returns, she isn’t the same. She can hear people think and move things with her mind. Nike hypothesizes that coming back from the dead has allowed her to use all of her brains at once. (Note: The movie refreshingly acknowledges that it’s a myth that people only use 3% of their brain, and instead implies that we can use the entire brain, just not all of it at once.)

But then the movie introduces elements from the aforementioned back-from-the-dead stories and combines them with the gory bits of Event Horizon. Or at least, that’s based on my own interpretation of the unexplained events in the last twenty minutes. What the filmmakers intended to convey remains somewhat confusing and (intentionally?) cryptic. Zoe’s strange behavior gets worse. She dreams of her lingering childhood trauma involving trapped neighbors inside a burning building. Details are sketchy at best. Eventually, her eyes turn black, her skin looks afire, and she begins killing people when they displease her. Did she go to Hell and come back infected by the place, like the characters in the aforementioned Paul W.S. Anderson yarn? Or is Hell just a myth, and her guilt and piousness collided along with her newfound mental abilities, transform her into a psychic killer with a Hell complex? The rushed finale refuses to pause and explain. And then the movie ends.

For such a notable cast, The Lazarus Effect makes little use of their talent. This critic is especially confounded by Mark Duplass’ presence—Mark and his brother Jay Duplass serve as writer-directors of thoughtful films like Baghead, Cyrus, and Jeff Who Lives at Home. Mark also starred in Safety Not Guaranteed, the freshman effort by Jurassic World helmer Colin Trevorrow. He’s an affable actor with nothing much to do here. The same goes for the rest of the cast, aside from Wilde, who effectively adopts the “There is no Dana, there is only Zuel” look of Sigourney Weaver in Ghostbusters. But with a runtime of 83 minutes, the movie is all build-up, while the payoff resorts to silly horror conventions, abandoning whatever scientific goodwill it had established. Gelb’s direction is serviceable, but the story takes such a nosedive that any other redeemable qualities crash and burn with the plot.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review