The Last Stop in Yuma County

By Brian Eggert |

The Last Stop in Yuma County once again affirms we’re living in a post-Coen brothers era of cinema. Writer-director Francis Galluppi replicates the Coens’ signature structure of dopey criminals who make bad choices and get themselves into delightfully entertaining, darkly comic situations, which usually end in bloodshed. In the aftermath of all the meaningless death, Coen characters often search for some order in the universe, ultimately finding, often with a note of melancholy, that none exists. There’s nothing so existential on Galluppi’s mind, nor the minds of other recent Coen copycats such as Shane Atkinson, whose LaRoy, Texas from earlier this year has a proportional helping of the criminally yet comically stupid. Galluppi delivers a wiry, rail-thin piece of B-movie entertainment that’s inflected with notes of Westerns and neo-noir. Its similarity to the Coens’ sensibilities hardly matters—most films have their antecedents—except the comparison highlights what Galluppi’s work lacks: the Coens’ philosophical underpinnings. Apart from that, the first-time feature filmmaker has delivered a taut, expertly crafted yarn with a premise too juicy to dismiss.

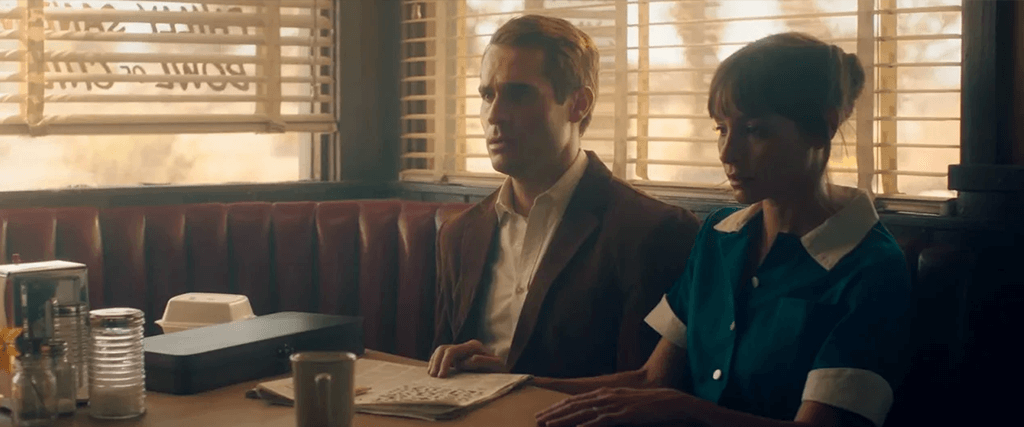

Set in the Arizona desert about 100 miles from anywhere, The Last Stop in Yuma County opens with an initial setup so good that it’s almost bound not to pay off. It’s sometime in the 1970s, and a man known only as The Knife Salesman (Jim Cummings) stops at a gas station only for its genial owner (Faizon Love) to explain that he’s out of fuel. A truck should be there “any minute,” and in the meantime, he could wait at the diner next door. Preferring to sit in his car, Cummings’ character turns on the radio just in time to hear about a bank robbery committed that morning by two men seen in a green Pinto with a dented rear fender. Having absorbed that information, The Knife Salesman resolves to wait in the diner after all and order a cup of coffee from the kindly diner proprietor, Charlotte (Jocelin Donahue), whose husband, Sheriff Charlie (Michael Abbott Jr.), dropped her off at work. Charlotte offers the diner’s specialty, rhubarb pie, and the two chat about how he’s on his way to visit his daughter, who’s living with his ex-wife and her new husband. Then, of course, the salesman sees the green Pinto pull into the diner’s parking lot, and the two bank robbers enter the scene.

One dim and the other insidious, brothers Travis and Beau (Nicolas Logan and Richard Brake) quickly realize they’ve been recognized. Beau, a devilish-looking sort who does most of the intimidating, issues a warning to Charlotte and The Knife Salesman: Say anything, and they’re dead. The robbers intend to wait either for the fuel truck or some diner patron with a full tank of gas. And while they wait, a comical number of others stop for fuel and find themselves stranded at the diner. There’s an older couple (Robin Bartlett, Gene Jones) who make small talk—and the more superficial the topic, the more tense the situation becomes. Then the lovers-on-the-run (Ryan Masson, Sierra McCormick) join, concealing their guns with the intent to steal the money in the bank robbers’ trunk. The diner also receives a visit from the none-too-quick Deputy Gavin (Connor Paolo), whose admirable desire to be the friendly neighborhood police officer distracts him from recognizing the simmering, sweaty tension in the room.

At one point in the movie, Travis tells Beau that the gas station owner is “not the smartest tool in the shed.” Beau tries to correct his brother by telling him the phrase is “sharpest tool in the shed.” Travis responds with a look of riotous confusion. This could have been drawn from any number of the Coen brothers’ movies, from Blood Simple (1984) to O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) to Burn After Reading (2008). But it’s here, along with many other moments that feel reminiscent of acidic Coen-brand humor. Even so, Galluppi keeps the viewer invested in the specifics, especially after a jaw-dropping turn reframes the scenario in the last third. A few shocks and displays of humanity at its lowest occur, leading to a fatalistic conclusion. The image of a bird in both the first and last shots might suggest some greater meaning to these events, but I didn’t decipher one, and the bird hardly presents a key to decrypt the movie’s lesson. In all likelihood, it doesn’t mean anything; it’s just an effectively told piece of pulp storytelling. That’s enough.

At one point in the movie, Travis tells Beau that the gas station owner is “not the smartest tool in the shed.” Beau tries to correct his brother by telling him the phrase is “sharpest tool in the shed.” Travis responds with a look of riotous confusion. This could have been drawn from any number of the Coen brothers’ movies, from Blood Simple (1984) to O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000) to Burn After Reading (2008). But it’s here, along with many other moments that feel reminiscent of acidic Coen-brand humor. Even so, Galluppi keeps the viewer invested in the specifics, especially after a jaw-dropping turn reframes the scenario in the last third. A few shocks and displays of humanity at its lowest occur, leading to a fatalistic conclusion. The image of a bird in both the first and last shots might suggest some greater meaning to these events, but I didn’t decipher one, and the bird hardly presents a key to decrypt the movie’s lesson. In all likelihood, it doesn’t mean anything; it’s just an effectively told piece of pulp storytelling. That’s enough.

The production cost a reported $5 million and was shot at the Four Aces Movie Ranch in Palmdale, California. Aside from a stretch of empty highway for the finale, that’s the main location, apart from a few brief scenes in a police station. Galluppi makes the most of his few resources, designing elaborate camera movements with his cinematographer Mac Fisken to keep the diner space interesting. Galluppi, who also serves as editor, creates an efficient tempo, never wasting a shot or second of footage, which keeps The Last Stop in Yuma County to a lean 90 minutes, with credits. The cast is filled with familiar faces from the independent film scene, including scream queen Barbara Crampton in a small but amusing role as a dispatcher. If Jones looks familiar, it’s because he’s the man behind the counter in that iconic coin toss scene in the Coens’ No Country for Old Men (2007). Cummings plays to type—a nervy part straight out of one of his own directorial efforts (Thunder Road, The Beta Test). In the final third, his character becomes central, leaving The Knife Salesman in a precarious situation reminiscent of both Josh Brolin’s character in No Country for Old Men and Steve Buscemi’s in Fargo (1996).

Perhaps I’m making too much of the similarities to the Coen brothers’ filmography, but there’s something about The Last Stop in Yuma County that feels like the work of a filmmaker who has spent years absorbing their cinema and wanting to pay homage. It’s not a detriment to the success of Galluppi’s movie; rather, it has a Tarantino-esque vibe, where every moment plays like the expression of an avid film enthusiast. However, Galluppi doesn’t seem interested in any deeper insights that would imbue the material with his perspective. It’s all pastiche, which has its place and proves entertaining, its simplicity notwithstanding. The movie premiered at last year’s Fantastic Fest, where rhapsodizing reviews overpraised its modest pleasures. What Galluppi has done isn’t a work of genius, but it’s the product of an unmistakable talent demonstrating what he can achieve with a small budget, strong character actors, a few locations, and plenty of imagination. If you have that, you don’t need to spend hundreds of millions on CGI, overpaid stars, and multiple locations across the globe. A solid script, two or three locations, and a great cast will do the trick.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review